Andrew Paul Wood – 21 December, 2019

Lara Strongman's elegantly composed essay on Henderson's time in Christchurch is another important document in highlighting the vigorous cultural activity in that city, without downplaying its provincial liabilities. Henderson was a member of The Group and a part-time teacher of design and embroidery at the Canterbury College School of Art from 1926 until 1941, where she “represented a direct link with modern European culture for the students, who referred to her as Madame”.

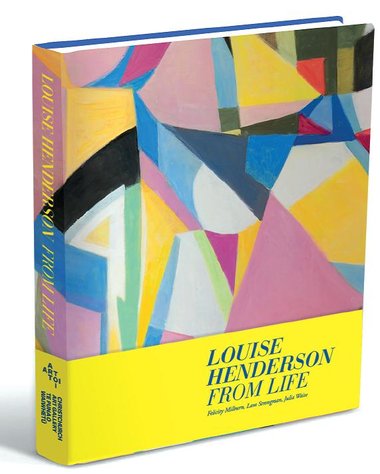

Louise Henderson: From Life

Eds. Felicity Milburn, Lara Strongman, Julia Waite

Other contributions from Christina Barton, Linda Tyler and C. K. Stead

Hardcover, coloured illustrations, 256 pp

Auckland Art Gallery 2019

ISBN: 9780864633255

RRP: $65.00

Louise Henderson (1902-1994) is one of the rarest of creatures in New Zealand art history, an artist who experienced the European avant-garde first hand—rather than as with many New Zealand modernists, a dabbler in half-understood cubism in pursuit of something else (and not from the periphery either)—who at the same time managed to accommodate a local modernist culture with its own agenda of national identity and a suspicion of what comes over the sea. French-born Henderson is one of my favourite New Zealand artists and definitely someone who should be up there in the popular consciousness with Colin McCahon and Gordon Walters. It is to be hoped that the exhibition this publication accompanies, a joint project between Auckland and Christchurch Art Galleries, will go a long way to redressing Henderson’s obvious importance. The book has a role in that and is the subject of this review.

Lara Strongman’s elegantly composed essay on Henderson’s time in Christchurch is another important document in highlighting the vigorous cultural activity in that city, without downplaying its provincial liabilities. Henderson was a member of The Group and a part-time teacher of design and embroidery at the Canterbury College School of Art from 1926 until 1941, where she “represented a direct link with modern European culture for the students, who referred to her as Madame”. It is a shame Strongman didn’t take more opportunity to examine the significance of such a statement, taking into account a syllabus that was still primarily based in the South Kensington Arts and Crafts movement, something that would not really change until the arrival of modernising British silversmith John Simpson in 1959 and his appointment to Professor and Head of the School in 1961. Of course, Henderson had long since upped sticks for Wellington by then.

We are treated to an important essay by Linda Tyler on Henderson’s work in textiles, a subject that has hitherto been much neglected. We are only now entering (or returning to) a cultural phase, long after Henderson, Theo Schoon, indigenous peoples, medieval guilds, and groups like the Bauhaus had got there, where the distinctions between art, design and craft are relatively ambiguous and more to do with function than aesthetic categories.

Julia Waite provides a thoroughly deep dive into Henderson’s cubism, her studies under Jean Metzinger (1883-1956) in Paris during one of her European sojourns, and her broader relationship with New Zealand abstraction. This is told with considerable passion and intelligence rather than, as is often the case with such texts, a dry retelling from the art history books, and it is a pleasure to see what Waite can do with an artist she clearly feels an empathetic bond with. I do feel, though, that a good picture of one of Metzinger’s paintings would have been worthwhile. I was unaware of Henderson’s friendship with the Turkish-born artist Hakki Anli (1906-1991), a relatively minor figure, but thanks to Waite his influence on Henderson is at once obvious.

Felicity Milburn follows up with an investigation of Henderson’s depiction of the natural world, revealing a potential exhibition around that subject alone. Perhaps the most unexpected contribution, however, is that of Christina Barton, who candidly revisits the exhibition Louise Henderson: The Cubist Years she curated at Auckland Art Gallery in 1991, providing valuable context of the critical/curatorial culture of the time, and the resources she drew on and/or rebelled against. I hope this kind of writing becomes a trend, not only for being informative because it gives a rare insight that many younger curators could learn from.

The brief personal reminiscence by C. K. Stead seems oddly out of place, not offering much personal insight into their relationship, or indeed Henderson at all, but neither does it particularly detract. It just sort of is, which is fine, but it seems an odd choice given the number of people still around who knew her and could make more informed comment about the art world at the time.

It is a beautiful book, full of wonderful images, but hey, it’s nigh on impossible to do a less than stunning book on Louise Henderson.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.