Norman Franke – 26 June, 2020

Even if Dornauf's large-format pictures sometimes contain traces of self-irony, most of his images are imbued with the sincerity of a child deeply absorbed in play. What distinguishes Dornauf's work from most other (post)modern takes on the expulsion from paradise is that his poetic depictions of the lost childhood paradise are not concerned with power, gender and knowledge but rather with innocence. And that they contain a deep, inconsolable undercurrent of melancholy.

In his magisterial 1400-page work about utopian thinking, audacity and progress in art and politics, entitled The Principle of Hope, the Neo-Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch dedicates the last chapter (‘Wishful Images of the Fulfilled Moment’) to visions and artistic anticipations of moments of supreme fulfilment in music, literature, religious and philosophical writing, as well as in visual art. The chapter culminates in a series of predictive statements, which, countering the alienating economic, political and cultural tendencies of modernity, envisage individuals and collectives that ‘have grasped and established themselves without exploitation and alienation.’ And, in what could be a motto for Peter Dornauf’s exhibition of recent paintings entitled The Barberry Days, Bloch’s visionary pronouncements end on an ever so slightly melancholic note about a utopian time and place where ‘there arises in the world something which shines into the childhood of all and in which no one has yet been: homeland’ (1)

It is not only in the Western tradition that, more often than not, art can be traced back to dealing with problematic periods in life, with suffering and conflict. On much rarer occasions, art deals with reminiscing, experiencing or praising moments of fulfilment and happiness. Especially in (post)modernity, the artistic depiction of favourable outcomes, sheer beauty and happiness is often suspected to be merely wishful thinking, trivialisation and/or kitsch. It has become a characteristic of much (post)modern art to distrust and deconstruct anything that is beautiful and harmonious. The ancient Judeo-Christian topos of an original harmonious space in the myth of ‘paradise’ or the ‘Garden of Eden’, for example, appears in the (post)modern age only occasionally as a quote or allusion and, even then, is mostly ironically broken. (2)

Dornauf is one of those rare contemporary artists whose work has been for decades centred around a notion of ‘paradise’ - albeit a paradise lost - and, more precisely, the lost paradise of a childhood in the rural Waikato. This applies to his paintings as well as his poetry and, in part, also his novelistic work. Even if Dornauf’s large-format pictures sometimes contain traces of self-irony (e.g. in a collage entitled Cowboy that contains a school book text about a boy named ‘Peter’ who pretends to be a cowboy in the Wild West), most of his images are imbued with the sincerity of a child deeply absorbed in play. What distinguishes Dornauf’s work from most other (post)modern takes on the expulsion from paradise is that his poetic depictions of the lost childhood paradise are not concerned with power, gender and knowledge but rather with innocence. And that they contain a deep, inconsolable undercurrent of melancholy.

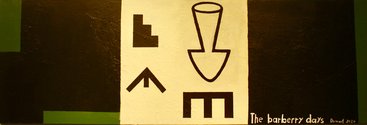

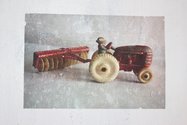

Each of Dornauf’s new paintings tells its own melancholic story. But the exhibition in its entirety can also be understood as one great lament con variatione. Unlike earlier figurative paintings of his Waikato utopia, Dornauf’s new style shown in Morrinsville is above all a mixture of text and image, whereby the images are often small photographs of landscapes and iconic objects from the 1950s (a Bedford truck, an old kitchen chair, established trees framing a paddock, a New Zealand-made Fun Ho toy tractor) transferred onto canvas. In his artist talk at the opening of the exhibition, Dornauf explicitly referred to the long tradition of New Zealand text images:

A large number of works in the show are text based. NZ artists have a long history working with text. It began with McCahon, but didn’t stop there. The love affair with words in the visual arts continued in the paintings of people like Nigel Brown, Peter Robinson, John Reynolds, Shane Cotton, Emily Karaka, to name a few.

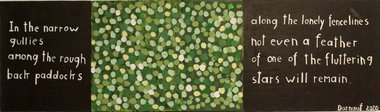

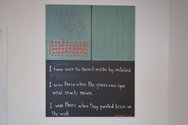

Most Waikato landscapes in Dornauf’s latest picture series are not evoked visually, but through poetry. The texts on the paintings’ panels stem mainly from the artist’s latest collections of poems (Metaphysical Midnight Cowboy Blues as well as Every So Often). They are of great simplicity and beauty. Many of the exhibition’s pictures are triptychs; words of poetry frame a central space or image that, in its minute detail, creates a brief, sharp shock of recognition and loss. Immediately impressive are also the layout and dark-coloured decorations of his canvasses; their particular charm is created by the evocative simplicity of patterns and stylised forms which often allude to very archaic and foundational art traditions (Māori petroglyphs, Australian dreamtime patterns, children’s drawings). Dornauf’s sense of proportions and the properties of colours and paint texture cannot be praised highly enough. The same goes for the dialogical arrangement of visual and textual elements in his pictures.

For Dornauf, the lost childhood paradise - enclosed by barberry hedges from which the exhibition takes its name - can be located in the rural Waikato, somewhere in the Gordonton area (the etymology of the word ‘paradise’, by the way, refers to an enclosed garden). Today, these hedges can only rarely be found, as barberry plants are considered invasive. Some of the fence posts that the artist’s father hammered in 70 years ago, however, can still be seen in their original places, as one of the poetic paintings tells us. The old childhood orchard exists only in memory and is evoked by alluding to the mythical garden in the Book of Genesis: ‘The orchard smelling of apples/The cherry red tractor once/Peaches and pasture deep with trees/and tall sheds/behind the barberry hedge/evening and morning/among the beasts of the field.’

In his opening talk, Dornauf referred to earlier attempts in art history to localise ‘paradise’ in mundane and familiar landscapes. In this context, the artist mentioned the influence of, inter. al., the American painter Edward Hicks (1780-1849). Hicks’ ‘naïve’ line-up of people, animals and plants in his picture The Peaceable Kingdom (after the biblical prophet Isaiah) shows the promised biblical end time of bucolic peace in the familiar landscape of his native Pennsylvania. Hicks painted the motif sixty-two times.(3) In a New Zealand context, it is the Waikato region that has often been chosen for the depiction of peaceful paradisiacal spaces and bucolic archetypes; an early example in literature would be William Satchel’s novel The Greenstone Door, which describes the Waikato shortly after the end of the Land Wars:

The huddled cultivations at the feet of the pas had spread out into great areas gilded over with wheat. Food-plants covered the rich virgin soil, and everywhere work was in progress… […] A profound peace […] had settled on the land. The people had advanced sufficiently to perceive its grandeur and beauty… The valleys of the Waipa and the Waikato became great gardens and granaries.(4)

In Peter Jackson’s depiction of ‘Middle Earth’ and ‘The Shire’ in his film adaptation of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the Waikato near Matamata stands in for a somewhat utopian or timeless pākehā dream of bucolic simplicity and easy living. The backdrop aesthetics of Jackson’s global box office success has turned the Waikato landscape into an internationally recognised icon of innocent country life and rural idyll. Glossing over the cultural, political and environmental struggles over and for the actual land, the ‘Hobbiton’ movie set represents a sanitised construct of pākehā country life, removed from all spatio-temporal or political actuality.

What distinguishes Peter Dornauf’s from Peter Jackson’s treatment of the Waikato idyll is precisely the former’s awareness of the places’ actuality, their mana, their historicity, transitoriness and melancholy. In ‘Hobbiton’, even the patina on the plastic props will be repainted when it fades away; in the ‘Barberry Days’, the old tractors are long since rusty, the orchards already axed, and the memories of teenage love have turned into private ‘Stations of the Cross.’(5) The childhood paradise of Dornauf does not consist of the timeless never-land of animated gnomes and elves but of visceral memories of real, vulnerable people. Referring to similar ideas of personal belonging and loss in a series of works called Eden to Ohaeawai by Shane Cotton, Dornauf submits: ‘The translation of one’s “ancestral” home with overtones of the sacred is a trope well used.’(6)

How do paradises get lost? You eat from the tree of knowledge. You discover your naked choices, your vulnerability and your mortality. You get kicked out in the cold like liars in a court or drunkards in a pub. But even the pious and the backcountry innocents are not spared the expulsion. As children they still experience a bliss akin to living in the garden ‘before the fall’: ‘In summer the paddocks shouted hosanna/He roamed acres, slept in trees and named the animals and counted sabbaths.’ But come puberty and first-year Humanities’ papers, the dark angel appears in the form of persuasive philosophy teachers and Darwinists. Dornauf’s coming of age novel Day of Grass describes the fall from grace and the expulsion from a childhood paradise of a young Waikato protagonist with a Christian fundamentalist background, Eason Vercoe. One of the panels in the Morrinsville exhibition is an extensive quote from the novel. Day of Grass describes a psychomachia, a soul-battle, between simple fundamentalist Christian beliefs and the sophisticated world views of (Neo-)Platonism and Charles Darwin that replace them. It is a rare and, to my knowledge, the only Waikato-based, New Zealand campus novel.

There are parallels between the author’s biography and the novel. It is also an almost archetypical story of the philosophical socialisation of an educated pākehā Kiwi into a philosophical materialist, pragmatist and no-nonsense adult. (7) In Day of Grass there is no reconciliation between the old religious ideas and the new philosophical and scientific world views. In his theoretical writings and some of his novels, Dornauf is a passionate and sometimes polemical and somewhat inveterate representative of an anti-religious Darwinian worldview.(8) And yet, in The Barberry Days, the artist still borrows the old powerful language of Genesis for his wistful poetry and his text paintings with their ‘overtones of something spiritual’. (9)

What is on display with The Barberry Days in Morrinsville is the art of a Waikato master at the height of his visual and poetic game. Unlike the above quoted Ernst Bloch, and unlike the eschatological thinking and artistic tradition of Judeo-Christian culture whose language he still partially adopts, in Dornauf’s works there is no (religious or political) way to regain the lost paradise except in those extremely short and sad glimpses of childhood bliss that mnemosyne affords. Poetic images conjure up the fading memories of homeland and reframe them in loss. It is a loss of cosmological proportions: ‘In the narrow gullies/… along the lonely fence lines/Not even a feather of one of the fluttering stars will remain.’ It is this deep and inconsolable melancholy that makes the beautiful Waikato images more poignant.

Norman P. Franke

(1) Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope, three volumes (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1986), p. 1376

(2) For a post-modern attempt to interpret the biblical paradise myths as a blueprint for discourses of desire and gender and power-differentials, S. Graham Ward’s ‘A Postmodern Version of Paradise’. In: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/030908929502006501?journalCode=jota

(3) https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-hicks/ There must be even more Dornauf paintings that revolve around the theme of a lost childhood paradise.

(4) William Satchell, The Greenstone Door, Whitcombe & Tombs,1957, p. 241

(5) From the poem Night Driving

(6) Peter Dornauf, artist talk, The Wallace Gallery, Morrinsville, 6 June, manuscript kindly provided by PD.

(7) For a discussion and contextualisation of male literary self-images and aspects of male (literary) socialisation see Kai Jensen’s seminal study: Whole Men - The Masculine Tradition in New Zealand Literature. Auckland University Press 1996.

(8) The author of this review and Peter have been artist friends for a long time; we have had passionate discussions about religion and philosophy as we agree to disagree on each other’s world views.

(9) Peter Dornauf, artist talk, The Wallace Gallery, Morrinsville, 6 June.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.