Jessica Hubbard – 1 July, 2020

The word 'tohu' has multiple interlocking definitions. It means to direct, to point the way, to gesture towards, to guide, it also means a symbol or a sign. You could say it suggests both the action and also the physical embodiment of that act - signs and symbols as a guide. The stars acted as a guide to a new world. Matariki acts as a guide to a new year. Can art likewise act as a guide to a new way of thinking or being - or a new/old way of thinking and being?

Wellington

Ayesha Green, Kauri Hawkins, Maioha Kara, Nikau Hindin

He Tohu

18 June - 11 July 2020

The exhibition He Tohu at Jhana Millers is designed to come to an end as Matariki comes to a beginning.

The word ‘tohu‘ has multiple interlocking definitions. It means to direct, to point the way, to gesture towards, to guide, it also means a symbol or a sign. You could say it suggests both the action and also the physical embodiment of that act - signs and symbols as a guide. The stars acted as a guide to a new world. Matariki acts as a guide to a new year. Can art likewise act as a guide to a new way of thinking or being - or a new/old way of thinking and being?

In a recent talk at The Dowse the artist Nikau Hindin suggested that we decolonise our idea of time. For many of us, most of us, almost all of us, our concept of time is tied in measurable bundles of mathematical exactness. Minutes, hours, days, months, years make neat packages and act as symbols of a Western concept of time devoted to clock-watching - divorced from reality, and from nature.

Nikau suggests we look back/forward to another perspective of time. One guided by nature and the stars. Her work, which rebirths the art of aute (or Māori tapa/kapa) draws on, or draws, the mātauranga that is sited in the rhythms and realities of the world we live in. A mātauranga that looks to the stars for signs to plant, to gather, to hunt, to explore - for the important things, the things that keep us alive and moving.

The first voyage of James Cook was navigated by the stars. Tupaia was a Tahitian navigator whose knowledge of navigation by the stars took Cook and his ships safely around the Pacific. Tupaia also worked as a translator for encounters with the tangata whenua of Te Ikaroa-a-Māui and Te Wai Pounamu.

Tupaia travelled with the ship’s naturalist Joseph Banks and botanical artist Sydney Parkinson. Tupaia himself made drawings during the voyage. Tupaia and Parkinson both died of dysentery on the trip back to England. Banks however employed other artists to complete the botanical illustrations begun by Parkinson and these illustrations were published 200 years later in the book Joseph Banks’ Florilegium.

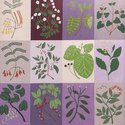

Ayesha Green has drawn on images from Joseph Banks Florilegium in her triptych, Kurawaka. Her purpose is to use mimicry to undermine the authority of the colonial powers in their mission to colonise knowledge through anthropology and classification. In her work she has selected 24 botanical illustrations and reproduced these three times across the three panels. The work has a flat plainness that, while attractive, shows how shallow and meaningless this concept of representation and classification can actually be. Separated from the rich mātauranga and lived cycles of the plants, separated from their context and tikanga, they are rendered ornamental and almost meaningless.

Maioha Kara’s work takes us from nature to the pattern and concept embedded in toi Māori. But I’m making a false dichotomy. I should say Maioha continues the work of using pattern and symbol to represent both te taiao and mauri. Maioha’s work echoes tukutuku, raranga, kōwhaiwhai, whakairo and the tivaevae of her Cook Island Māori whakapapa to explore the holistic energy of the stars and the cycles of time and space. Her work is rooted in symbol. It prompts me to consider how much more richness this language of pattern provides - how many stories and histories there are available to those who are open to learning.

There’s a story, no, a history, or perhaps an explanation or a perspective. There’s an explanation for the stars of Matariki, ngā mata o te ariki o Tāwhirimātea - this means the eyes of the god Tāwhirimātea. The explanation says that Tāwhirimātea, the god of the weather, was so upset that his siblings forced apart their parents Papatūānuku and Rangi-nui, that he tore out his eyes and threw them up to his sky father Rangi-nui. There they stay as the stars that make up Matariki.

Kauri Hawkins’ work, Taawhirimaatea, draws quite literally on concepts of tohu. He uses the material of road signs, but in these signs the arrows sweep in multiple directions - like a weather map, like the wind. What direction do they point us in? Perhaps they point us to mātauranga, to ako? But perhaps they also have another more current meaning, intentional or not. If ever there was a time to look to the climate, to look to the weather, to consider our own hubris, it is now.

For me, this exhibition guides us to an opportunity to consider the cultural construction of even the most basic forms of knowledge and, if we haven’t already, to open up to other forms of mātauranga. There is never a bad time to learn.

Jess Hubbard

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.