John Hurrell – 2 July, 2020

In fact, there is something highly performative and bodily (on the part of the artist) in this show—with its emphasis on transitive verbs and violent actions. A mental picture of Robinson indulging in crazed infantile behaviour is generated—even though he, when he chooses, can through his work be an accomplished mimic or comedian. It is also risky to be too confident here of the presence of genuine impulsiveness, for as an apparent formalist who likes to weave in the occasional politically coded signifier or hint of postcolonial narrative, Robinson is cunningly nimble-footed.

Auckland

Peter Robinson

Rag Trade

25 June - 4 July 2020

Peter Robinson’s new installation is presented in a high studded, grey-walled, polished concrete-floored, industrial warehouse organised by Sarah Hopkinson in Morningside. A temporary space, it is square in floorplan with a high roller door. It is obviously designed for storage and the stacking up of loaded pallets.

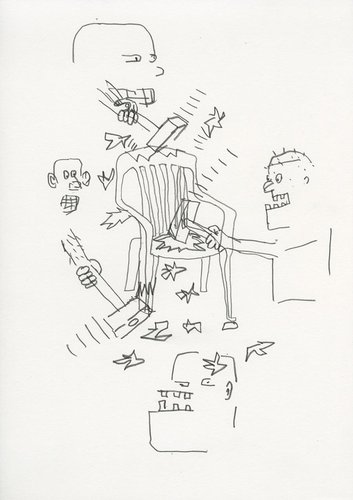

Robinson’s show runs parallel to a similar presentation in Melbourne, Notations (click here), at Sutton Gallery. The high Morningside ceiling he copes with effortlessly, for although the emphasis is on the floor with its scattered ‘carpet’ (of smashed up plastic chairs, strewn coloured sheets of die-cut offcuts, chopped up soft-drink bottles, broken laundry baskets, shredded balloons, dismembered garden tubs, dismantled paint buckets, flattened pottles, pulled apart sections of PVC piping, exposed sponge-mattress stuffing, sliced up rubber gumboots and gloves, squashed basket-balls and draped cotton rags)—and the walls are ignored—long doubled-over aluminium struts reach upwards, bearing moth-eaten balaclavas and signthetic wigs to present heads on pikes.

Such severed ‘body-parts’ establish the mood. A grim anger is suggested in the intermingled shattered objects that look as if they were spontaneously destroyed on the site. They don’t look as if they were demolished elsewhere—for the sake of mischievous comedy or intellectual curiosity—and the pieces then transported. Their destruction seems motivated by a hatred for these tacky and nasty consumer items themselves, accompanied by a cathartic release, but channelled through ‘templated’ traditions linked (amongst other things) to certain works by Morris, West, Pollock and Basquiat.

In fact, there is something highly performative and bodily (on the part of the artist) in this show—with its emphasis on transitive verbs and violent actions. A mental picture of Robinson indulging in crazed infantile behaviour is generated—even though he, when he chooses, can through his work be an accomplished mimic or comedian.

It is also risky to be too confident here of the presence of genuine impulsiveness, for as an apparent formalist who likes to weave in the occasional politically coded signifier or hint of postcolonial narrative, Robinson is cunningly nimble-footed.

While the work exudes a veneer of the processual and aleatoric, Robinson still clearly maintains careful control of all elements so that they playfully interact via layering, juxtaposition or penetration. Every element’s position is considered, for after all this is a form of optical theatre. As options, the mutilated materials he concentrates on are varieties of plastic, rubber, cotton rags (from abandoned clothing), woollen children’s onesies and balaclavas, glitter, aluminium and tin; no wood, no glass, no ceramics, no iron, no earth, no unprocessed natural fibre.

Rag Trade, with its continual spread and lack of discrete units, is paradoxically more akin to The Humours (2005) than say Fieldwork (2018). It is closer to a ‘carpet’ sensibility, yet with its lack of warmth or smirking vulgarity is snarly, bristly, and not as creepily clammy or greasy as the former was. Like Fieldwork, it’s much airier, while maintaining a cohesive density. The scattered shards and spiky slivers, and thrown down (out of fashion) hideous garments, accentuate that industrial iciness.

Robinson seems to be having a hissy fit (for various political or sociological reasons) but besides indicating emotion, I think he is also preoccupied with experiential space and how to confront the towering-above, unattainable hanger-like ceiling: how to get to the unreachable from the floor.

It can be argued that the two hypotheses are one and the same, and that by ‘reaching for the sky’—he has much more elevation to play with than in the Sutton space—he is using the height as a trope for aspired Māori social and economic mobility, expecting you to notice. Yet those impaled heads are a worry. Robinson may be a sneaky Ngāi Tahu activist dressed in formalist clothing, but he’s waving warning signs too. Expressing ambivalent hesitations and uncertainties about striving to attain desired happiness and any societal utopia.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.