John Hurrell – 24 July, 2021

Culbert noticed that both intense light and extreme shadow dissolve form and—by degree—compress distance. Despite studying painting at the RCA in London and becoming a brilliant ‘neo-cubist' practitioner, his international art career took off through his sculpture (he had a show at the Serpentine) with his seventies camera obscura projects that usually featured projected multiple images of a glowing light-bulb.

Auckland

Bill Culbert

Slow Wonder

Curated by Julia Waite

3 July - 21 November 2021

Displayed in nine rooms with 54 artworks, including two immersive installations in their own darkened spaces (as if we are inside giant cubes), Julia Waite has assembled a snappy new survey to remind us of the subtly of this constantly revisiting NZ born (but France and [occasionally] England-based) artist’s observations about perception and the experiential, and the varied ways in how they mesh with language.

As the exhibition’s title says, these Bill Culbert (1935-2019) works take time to gradually work their magic. They encourage prolonged scrutiny and careful analysis, and a key awareness that looking at the world directly and looking at a photograph (as an artefact) of part of the world, involve two very different bodily and cognitive processes.

This is confused by the fact that some of his light-fixated sculpture is absolutely impossible to accurately photograph, for during everyday circumstances the human eye is superior to a camera in picking up fine detail.

Wonderfully in this show, many of the phenomena the viewer detects are ‘found’ wit-aspects of the laws of physics that Culbert alerts us to—or manipulated wit where he has organised certain material juxtapositions to ‘fool’ us or make a joke about categories, such as with different types of bulb or skeletal silhouette.

In the line-up there are 24 b/w photographs and 4 coloured ones, and of course lots of portable ‘light’ sculptures (another 24). Most works show how utterly intrigued he was by the liquid optical properties of light (especially emanation, reflection and refraction) and shadow (how it spatially collapses, compresses or elongates form).

Culbert adored delicate translucent colour and worn (time-evidenced) texture, so while the latter is salient in most of the b/w photographs, the former only really surfaces in the sculpture that incorporates thin plastic, and a few photos, in three rooms near or at the end.

Culbert also noticed that both intense light and extreme shadow dissolve form and—by degree—compress distance. Despite studying painting at the RCA in London and becoming a brilliant ‘neo-cubist’ practitioner, his international art career took off through his sculpture (he had a show at the Serpentine) with his seventies camera obscura projects that usually featured projected multiple images of a glowing light-bulb.

About the same time, he began making tonal discoveries with photographs of ordinary objects interacting with light, and then—as shown here—sculptures using discarded translucent plastic containers, or leather and metal ones that became metaphors. Later came the illuminatory architectural modifications where white fluorescent tubes were coordinated with suspended tubular office chairs, or freestanding lamp stands, elsewhere lined up coat-hooks on a wall, or carefully ‘scattered’ hollow coloured plastic objects on the floor.

Curiously in total, within his practice, Culbert‘s varieties of artwork and research are actually more demonstratively complex than the above. Other topics of interest for example include house, furniture, wineglass and car design (a logical consequence of sound observation); the ritualistic mores (eating and drinking) of neighbourly or friendly conviviality; the casual French treatment of inorganic waste; tightly stacked grids bearing saturated chroma; his love of drawing.

Let’s look now at a dozen of what I think are Culbert‘s most striking works, sequenced chronologically—items I consider particularly remarkable. Humdingers picked out of this cracker show.

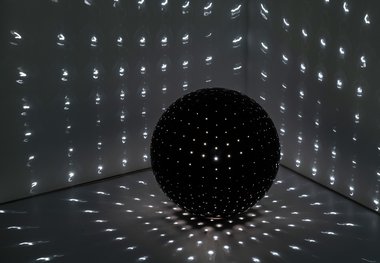

(1) Cubic Projections, 1968, shows his transition from portable cubes with gridded sides of repeated glowing projected marks (or parts of bulbs), to that of a space where the viewer is now seemingly inside the box. The gallery room has become the dark cube and the cause is a black sphere lined with perforations. Those wee holes project out rows of glowing filaments (in small bulbs) that when covering a corner with a ceiling, two walls and floor, look just like the inside of a right-angled planar intersection; the inside of a cube. It is unnerving.

(2) Jug, Windowpane, 1980. In this b/w photograph a white enamel water jug lies flat on a wooden table. It is very carefully positioned on top of a glowing floor-reflected image from an adjacent four-part window where one quarter has a mottled rippling effect—as if disturbed water—caused by imperfections in its glass. Culbert wittily makes it appear to be spilling out of the jug’s spout.

(3) An Explanation of Light, 1984, is also about light interacting with glass. A set of double French doors leaning against a large tinted gallery window has its windows pierced by diagonally aligned illuminated fluorescent tubes. According to where you are standing, these white lines (with white looping power leads) are reflected sloping in the door-window glass, and also in the dark museum window behind, where the lines bounce back to the inside of the doors, and so—perpetually reoccurring—fly back off, multiplied to fading infinity out over Albert Park.

(4) Small Glass Pouring Light, 1985, takes this theme further: Twenty-five verres bistrot glasses are spread out over a long table with three suspended carefully controlled light sources that shape the direction and tonal depth of the subsequent radiating bulb-shaped shadows. As the wine in the filled glasses gradually evaporates it leaves red rings on the sloping inside surfaces of the transparent inverted cones. The glasses are freshly topped up every morning.

(5) Cascade, 1986: Here four ascending and diminishing horizontal rows of fluorescent tube-pierced detergent bottles are positioned on the wall adjacent to the descending staircase at the end of the corridor. The varied (but muted) colours of the inverted transparent containers are repeated and carefully distributed, creating a rhythmic musicality within the large bottomed four-sided four-layered polygon.

(6) Stand Still, 1987, is a sculpture made of six fluorescent tubes of different lengths standing vertical in a row. The long bulbs themselves have become lampstands. Placed inverted over five of their ends are a selection of coloured fabric lampshades, a plastic bucket and a couple of large translucent jugs. Two of the glowing stems have shades stuck halfway up, an amusing touch.

(7) Central station, 1990, is a large group of spindly black lampstands with fluorescent tubes positioned at odd angles, tilted at their tops, replacing the usual bulbs and shades and attached halfway along their sloping glowing lengths. At floor level their bases are usually spiralling scrolls and sometimes empty V-shaped magazine racks with dark red cord woven into their sides. The vertical stands seem anthropomorphic and collectively become quite comical, as if satirising a snooty, very superior, social gathering.

(8) Sunset I, 1990, is a coloured photo of a half-filled Sunlight detergent bottle with a frosted bulb and unused Bakelite fitting mounted on its cap. It is placed on a low wall so that the sun sinking into the sea can be detected immediately behind it. It is not directly visible but the sky around it is glowing, as are the twinkling golden drops of detergent sticking to the inside shoulders of the bottle, and the top surface of the enclosed liquid. It is marvellously clever, yet brilliantly simple.

(9) Sunset IV, 1992 demonstrates how photos can create unexpected fictions. In the same series as the Sunlight bulb from the previous year, this large coloured image looks like a monumental linear steel structure built on a distant ridge and now seen during sunset. In fact these dark skeletal lines are very close to the camera, a jumbled assortment of lampshades piled high with all their fabric removed. The illusion of some distant construction is impressively convincing.

(10) In Seven Yellow Cloroval, Easter Island, 1994, seven yellow (once toxic) jars from Portugal are resting on a narrow cardboard box in which is hidden a horizontal fluorescent tube that shines up through their removed bases. We see indented seven skull and crossbones which, judging from its title, possibly refers to the well known, but now considered historically dubious, myth claiming that the ‘Long-Eared’ tribe was exterminated by the ‘Short-Ears’, when slaves successfully turned against their masters. Whatever the reasons behind Culbert’s thinking, the yellow glow with the small skulls exudes a sinister ambience.

(11) Bucket, Croagnes, 2012, is a coloured photograph of an abandoned anaemically pink bucket lying on its side. The sunlight passing through it makes its paler base seem quite thin, especially when compared to the darker conical walls. We might also notice that the curved plastic handle is very pale as well; in fact even more so. One assumes that the walls are thicker. It is hard to imagine why, as the circular base takes the weight.

(12) Lightline, 2014: At head height this is a continuous line of six glowing fluorescent tubes held on the gallery corridor’s white wall by six different types of ornate brass coat-hook. It is a wonderful work with great simplicity. One of the tubes is shorter than the others, but this is not at all obvious. The work functions as a kind of long horizontal arrow between the two Culbert items on either side (one round the corner). It seems to say, ‘Come along…What do you think of this next work?’ An incandescent but ‘invisible’ vector, it modestly ignores itself.

There you have it. If you are lucky enough to possess a good pair of eyes, and you enjoy using them—and thinking about what you are looking at—then this extraordinarily dynamic show is essential visiting.

John Hurrell

![Bill Culbert, Blackball to Roa, 1978, kerosene tin, fluorescent tube. Installation photography by Jennifer French. [I think this is a joke about the old kerosene lamp with a wick you used to take camping--Ed.]](/media/thumbs/uploads/2021_07/5_2021_15_1_Bill_Culbert_Blackball_to_Roa_1978_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.