Peter Dornauf – 4 March, 2022

The work of Australian textile artist, Teelah George, embraces the practice of mounts, edgings and enclosures—and does it with knobs on. Her mantra is: If you are going to have a frame, then let's do it properly. As a consequence, some displays present an extravagant and theatrical scaffolding that in its art nouveau configurations, gives a deliberate nod to the melodramatic and overblown framings of the past.

Hamilton

Teelah George

The Rose has Teeth in the Mouth of the Beast

23 February - 19 March 2020

“I do like the frame.”

Sometime in the second century BC someone drew a border around an Etruscan cave painting, and thus was born the frame which decorated and protected works of art up until it was deemed a distraction in the late 1940s.

These boundaries encompassed everything from the ‘Old World Cathedral’ look—complete with gilded curls, baroque swirls, and carved acanthus leaves thrown in for good measure—to the rawer and unsentimental style favoured much later by members of the American Ashcan School in the early twentieth century.

With the arrival of the Abstract Expressionists, however, the frame was discarded altogether. Nothing was to complete with the aesthetics of pure colour, line and form. Chocolate boxy borders were verboten. The frame, after centuries of service, was dead.

But now, in the twenty-first century, the frame is back. After decades of devaluation, the frame has returned, though not necessarily as a window on the world. Not literally anyway.

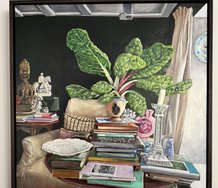

This trend is exemplified in an exhibition currently showing at the Laree Payne Gallery, Hamilton. The work of Australian textile artist, Teelah George, embraces the practice of mounts, edgings and enclosures—and does it with knobs on. Her mantra is: If you are going to have a frame, then let’s do it properly. As a consequence, some displays present an extravagant and theatrical scaffolding that in its art nouveau configurations, gives a deliberate nod to the melodramatic and overblown framings of the past.

They are made of brass—winding, curling and disporting themselves in bold and inflated fashion—and in so doing become an art work in themselves. There is nothing demure and understated about these borders. They declare emphatically that they are integral to what you are looking at.

There is also an unmistakably organic element in their forms, and as such they find a kind of kinship with elements that make up the title of the show: The Rose has Teeth in the Mouth of the Beast. This comes from one of those gnomic sayings Wittgenstein constructed. He enjoyed playing “language games” after the Tractatus proved too linguistically confining.

There are various ways one can interpret this, but the artist has chosen to read it as somehow endorsing abstract practice, while she works in colours that allude to floral blooms.

And this is exactly what she has done in her tapestry-like textile pieces, that are hand embroidered, where the stitching gives the appearance of fur. They are, essentially, abstract creations which display subtle colour ranges, employing sometimes ridged formations that look like aerial views of walled paddocks or labyrinth-like configurations.

These connect to the subject of memory—hollows, dents and depressions made by objects no longer present—marks that allude to a past now unrecoverable, known only by the pockmarks left by a previous life. Other works reference the colours of flowers, fallen petals left bruised on a pavement; or the changing tints and shades of a mutable sky. In these works, depth and modulation of colour work their sensory nuances and overtones on the mind.

This exhibition is a little more minimalist than the last show at the same gallery, if one discounts for the moment the florid frames, particularly displayed around the larger embroideries. The frames on the smaller ones are not quite so extravagantly demonstrative, but still in bronze, heavily textured, and following the eccentric contours of the asymmetrical wonky borders of the enclosed work.

George crosses the boundaries between high and low, combining a refined abstract aesthetic with humble stitch work. The result is, in part, something approaching a mini Rothko-esque emotional encounter.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.