Peter Dornauf – 11 May, 2022

In this wild collection of disparate ephemera, the mood of light and dark play off against each other in what amounts to be a visual stream-of-consciousness, a riotous creation that roams over a vista of a great many disparate things, including bits of wire bent into words like “ADRIFT” and “YES YES YES.” It becomes a cacophony of visual enjoyment, to be read like a novel that takes time and even more time to interpret.

There is a lot to see in Omega Man, a show of new works by Hamilton artist, Joseph Scott, at Never Project Space. This large installation piece covers a lot of ground and a lot of wall space, not to mention the floor. It is a packed house of a myriad images and objects, all jostling for our notice, a claim on our time and attention span, each part of which is meticulously placed and composed.

What this giant collage represents is a kind of cornucopia of the world in various throes of woe, delight and distress, a thousand voices—each with an affliction, a sad tale to tell, a point to make—downbeat mixed with up-beat, irony butted up against polemic, cliché versus cliché.

It is constructed as a kind of story that begins at the beginning, the best place to begin. Indeed, the artist is at pains to make this clear with instruction of where to start your tour in the gallery itself. It begins at the far wall, moving in a counter clockwise direction. So far, so unconventional.

The wall text says, LET’S BEGIN, marked out in bold white lettering against a black background with an arrow pointing the way. But just before we proceed, there, positioned on the wall just prior to this entry point, is a brand new commercial off-the-shelf product consisting of a child’s paint set. It’s unopened, complete with brushes and paints, together with a plastic model of a white rhino, which it seems might be the real object of the art exercise. All is safely installed inside the box which reveals its contents behind a transparent plastic window.

At the end of the show, after making one’s way around the walls, lefthandwise—through a plethora of images, text, objects, objet d’art, drawings, found objects, posters, torn pages, books, and altered readymades—we find, at the completion of our journey, an identical plastic white rhino toy, out of the box, looking a little grubby and a little soiled, attached to the wall, but hovering over a small wooden shelf that suggests it should really belong there. The kicker here is that this rhino has had its horn cut off.

That, in essence, is the narrative in a nutshell. The story of the Fall of Man, plummeting from innocence to experience.

But in between these two bookends, one finds, in various clever guises, the story spelt out in finer, equally sardonic, detail. The directional black arrow, at the start, actually points to a small piece of triangular rock positioned on a shelf with a postcard sunset backdrop. Creation of the world. So far, so pretty. But from here on, things get a little ugly.

First, and forebodingly, on a small torn slip of paper pinned to the wall, is pressed a piece of discarded green chewed chewing gum. Adjacent to that is a tiny polemical pamphlet, 1940s vintage, entitled The Bible Versus the Evolutionists, by Enoch Coppin. It is placed next to a pencil sketch of Fred Flintstone, which butts up to a KFC keyring, which hangs over a text from Samuel Becket’s Molloy, the page of which is all crossed out except for the following lines:

The fact is, it seems, that the most you can hope is to be a little less, in the end, the creature you were in the beginning and the middle.

Such mordant observations are accompanied by found printed images alluding to the violent propensities of both men and animals, dinosaurs included. Dismantled circuit boards play off against these pictures, variously purloined from incongruous sources. Nearby is another small shelf that holds a pile of vintage books, the topmost being The Achievements of Western Civilization. We are starting to get the picture at this stage, as the smorgasbord of material begins to pile up.

An upturned plastic bag gets the treatment with a pair of painted snarling teeth and a couple of glaring eyes made from ping pong balls. A Micky Mouse face morphs into a clown’s face around which are pinned a variety of printed texts taken from diverse sources. They ask an assortment of pointed questions, like:

“Is there a limit to scientific growth?”

“Are human rights uniquely ‘western’ ideals?”

Or various bits of banal advice, like - “Walking is man’s best medicine.”

Sometimes the links between image and text are a little more physically removed, so that after one has read, “Really? Thanks a lot, you cheating bastard”—a line from the film, Omega Man, (accompanied by a sketch of a bride)—one later comes across the iconic image of that same embracing nude couple advertising The Joy of Sex. Or a small cardboard copy of The Ten Commandments.

Part of the fun of this show is finding these connections, point and counterpoint, discovering family relations.

A pretty porcelain group of figurines, depicting eighteenth century aristocrats, complete with faded price tag ($3), jostles with robot figures, a bottle of correction fluid, a torn comic book page with a picture of Tarzan extolling the virtues of modern life, a clothes rack with three singlets (one white, flanked by two blue), and another set of old worn books, one entitled, The Joy of Living and How to Attain it.

The most poignant piece of all this ‘detritus’ would have to be a text on a card in a child’s slightly clumsy handwriting:

We went to Geraldine. On the way back to the camping ground we went to an old church and saw the graveyard.

This captures just a tiny portion of the material the artist has carefully and judiciously selected and arranged on the gallery walls.

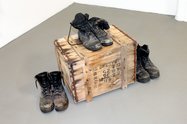

Then there are the sculptural pieces. My favourite would have to be the extremely worn working men’s boots, three pairs arranged around an old crate. The black boots remind one of those same boots van Gogh painted and the association is apposite. The boots themselves are seriously oversized, astonishing in itself, but it is the title N.E.E.T. (Not Engaged in Employment Education or Training) which provides a critical edge to this ensemble, with its new indicator rate on youth unemployment.

While looking at this, one recalls an earlier tiny piece of the patchwork collage (a torn copy of a Kaikorai Valley High School library record card pinned to the wall) along with mounted wooden ice cream spoons, a Fortune Cookie wrapper and several cute miniature ceramic English cottages in immaculate rose gardens.

In this wild collection of disparate ephemera, the mood of light and dark play off against each other in what amounts to be a visual stream-of-consciousness, a riotous creation that roams over a vista of a great many disparate things, including bits of wire bent into words like “ADRIFT” and “YES YES YES.” It becomes a cacophony of visual enjoyment, to be read like a novel that takes time and even more time to interpret.

Scott’s point of reference is the title of the show, a direct allusion to the film made in 1971, a post-apocalyptic drama that finds echoes in our own pandemic era. These are troubled times, almost biblical in proportion, and he gives himself the task of attempting to make some sense of it all, or at least provide some acerbic comment on the whole mad shooting box.

This is one of this artist’s best installations, a crazy, delightful, troubling exploration of contemporary life, one that rises above singular political agendas and touches on broader existential themes. It is refreshing to see him traversing such territory in such an engaging, clever and droll manner. An exhibition rarity.

Peter Dornauf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.