John Hurrell – 7 December, 2022

Besides her and Rivera's accomplishments, the show looks at Mexican society and its changing dynamic, with the role of artists documenting shifts—though Kahlo is the central hub. She inherited a Tehuana (Indigenous matriarchal community on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec) sensibility from her mother, and a passion for art from her father, a highly respected architectural and socialite photographer.

Auckland

Works from the Jacques & Natasha Gelman Collection

Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera: Art & Life in Modern Mexico

15 October 2022 - 22 January 2023

An immensely informative blockbuster about Mexican modernism and the pivotal roles of Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) and Diego Rivera (1886-1957)—a wife and husband team (1940-1954)—this richly satisfying touring presentation amazes through its exhibits (from a wide ranging coterie) all coming from the one private collection. The selection features paintings, drawings, lithographs, film clips, photographs and collages, many swirling around the two star personalities, and set against a detailed timeline of Mexican history.

Although not focussed solely on Kahlo like the Adelaide Arts Festival survey that many NZ artists visited in 1990 (seven years after Hayden Herrera’s biography took the international artworld by storm), this presentation looks at her marriage to Rivera and their contribution to Mexican modernism.

The show features a cast of colourful personalities clustered around Kahlo, Rivera her celebrity muralist husband, various family members, lovers, surgeons (for spinal operations), artist friends and colleagues, so that all together these intermeshed narratives look at the nature of salient subjects such as the self, love, national identity (Mexicanidad), place, modernism, representation and personal symbolism.

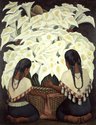

Whilst Rivera was usually a comparatively ordinary oil painter, he is much more famous for his massive, politically strident, communist-driven, fresco murals that are crammed full with figures and symbols and quite formally rigid. Kahlo on the other hand, was an inventive, highly imaginative portrait painter, with a flair for dynamic self-portraits and astoundingly resonant, personal symbolism set in an intimate, more fluid space. Often linked to Surrealism through her admiring social connections, her work is really too individualistic and controlled for that—despite its vivid interiority—and not about the subconscious mind.

Although she became an artist much later than Rivera, Kahlo quickly superseded him in reputation—though their respective styles and subject-matters were very different. A beautiful, observant, witty and passionate woman who suffered from a series of appalling accidents and ailments that dogged her all her life, she succinctly expressed her excruciating pain through tropes and chosen objects that rarely became maudlin—mixing them at times with exotic local plants and animals and playful humour.

Besides her and Rivera’s accomplishments, the show looks at Mexican society and its changing dynamic, with the role of artists documenting shifts—though Kahlo is the central hub. She inherited a Tehuana (Indigenous matriarchal community on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec) sensibility from her mother, and a passion for art from her father, a highly respected architectural and socialite photographer.

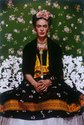

We see lots of wonderful contextual photographs and film clips of Kahlo and Rivera, the highlight being a suite of colour photographs of Kahlo by Nickolas Muray, taken in New York.

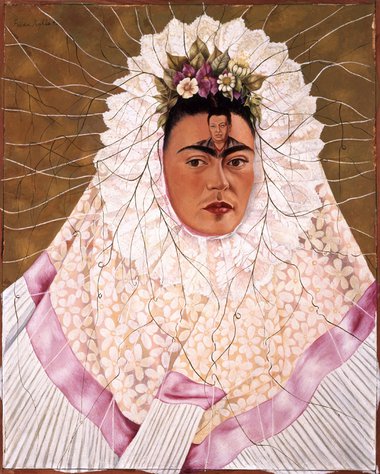

Several famous Kahlo paintings are included, such as Self Portrait with Monkeys (1943); Diego on my Mind (Self Portrait as Tehuana) (1942); Me and My Doll (1937); Self Portrait with Red and Gold Dress (1941); and The Love Embrace, the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Senor Xoloti (1949).

As you’d expect, most of the Kahlo self portraits are serious in tone, but often the images depicting Diego (at times comically infantile) whom she adored, are extremely amusing, even though their relationship was at times rocky.

In some of the photographs of Kahlo she is clowning for the camera, such as wearing a doily on her head as a bridal veil. In one photo of the couple’s sitting room, we see amongst assorted collectables, a life-sized cardboard and paper figure of Judas Iscariot, covered with explosives and wicks, ready for an exuberant detonation.

Her pencil drawings are also highly engrossing. These include an imaginative reworking of the Statue of Liberty, Lady Liberty (Workers of the World Unite) (c.1945) with a dramatic political realignment; and a wonderful undated drawing on a foot surrounded by tree roots, an eye, heart and other body parts. There is also Frida and the Miscarriage (1932), a moving lithograph of herself as a ‘visible woman’ showing her body split into light and dark, a developing fetus, and with a pantheistic sensibility, the planet earth and plants growing in soil.

I would have liked to have seen more documentation of Rivera‘s murals (surprisingly many are in the States), although the huge Detroit Industry Mural (1931-32) in the Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, gets some coverage, and there is a selection of coloured prints depicting details from the murals. Locked into the architecture, their scale and multiplicity astonishes.

In the exhibition, the elegant photographs of Lola and Manuel Alvarez Bravo (wife and husband) play an important documentary role recording Tehuana life, but Lola’s panoramic Surrealist photomontages are also spectacularly sensational.

Her striking b/w portraits of Kahlo are an important contribution too. Kahlo is the star of this show, and for good reason; her distinctive paintings never lacked confidence and they still seem extraordinarily fresh today. A cynic might think them narcissistic but they are not remotely vacuous, only mentally compelling.

This show is also an excellent adjunct for A Space to Dream, the glorious South American multimedia survey that came to AAG in 2016, even though it focusses on one country only; and mostly two artists. It highlights the richness of Mexican culture, and the high octane creative energy of certain driven individuals. In Aotearoa NZ society, Communism and Surrealism have never gained much traction, so that helps make this presentation even more intriguing.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.