John Hurrell – 27 July, 2023

Janine Randerson's selection of seven pertinent art projects—initially picked for online access as part of Te Tuhi's involvement as a ‘weather station' in the World Weather Network, but now transmuted to a gallery format (as another option to check out) and occasionally edited or reversely extended—utilises the architectural interiors and upper exteriors of the Te Tuhi building for a more bodily involvement.

Auckland

Breath of Weather Collective, Denise Batchelor, Janine Randerson, Julieanna Preston, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila, Layne Waerea, Maureen Lander, Mick Douglas, Nujoom Alghanem, Paul Cullen, Phil Dadson, Rachel Shearer, Ron Bull, Stefan Marks, Stìobhan Lothian

Huaere: Weather Eye, Weather Ear

Curated by Janine Randerson

Gallery presentation: 4 June 2023 - 5 August 2023

The actuality of climate change, its rising temperatures and the alarming consequences of altered global weather patterns, is a subject most people on the planet these days are cognisant of, if not deeply alarmed—through personal observation or following reports in the global mass media. In fact, the changed weather patterns, plus the economic situation, have encouraged widespread depression. It is palpable. You can sense it all around you. Especially here in Auckland.

Consequently there is a view that shows like this are a waste of time. It argues that it is far too late for any art to be of benefit. Yet, even if you agree, you can give up on the pragmatics and still think that art in all its manifestations is interesting—so why shun this variety?

Janine Randerson’s selection of seven pertinent art projects—initially picked for online access as part of Te Tuhi’s involvement as a ‘weather station’ in the World Weather Network, but now transmuted to a gallery format (as another option to check out) and occasionally edited or reversely extended—utilises the architectural interiors and upper exteriors of the Te Tuhi building for a more bodily involvement. This meteorological theme is related to many other exhibitions around the world, like the recent Avant l’Orage show at the Bourse de Commerce / Pinault Collection in Paris.

This project though, is exceptionally well focussed in its emphasis on climatic shifts and rising temperatures, their damaging effects, and our bodily encounters with such maverick elements, outdoors. And on the social dynamics of collaboration.

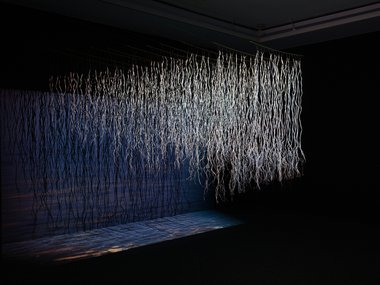

Maureen Lander, Denise Batchelor and Stiobhan Lothian’s installation, Ngaru Paewhenua (the wave that comes to shore), features a video projection of small foam-laden waves creeping up a beach, beneath a triangular formation of dense undulating vertical stalks of dried harakeke suspended from the ceiling. With Lander’s inverted triangular Wave Skirt on the adjacent outside wall, made of muka, harakeke and clear acrylic oblongs with bubble-like cut circles, it seems that the islands of foam skittering across the soaked sand represent waves of Māori migration.

They could also reference in today’s terms, direct pollution or water temperature increasing; or the inverted triangle, pubes; and tides, menstruation. There is a clever poetic and political (feminist) ambiguity in these works that focuses on transience. In very broad terms, one is about arrival of a particular community, the other the annihilation of a whole species.

Ron Bull, Stefan Marks, Heather Purdie, Janine Randerson and Rachel Shearer’s large installation, MĀKŪ, te hā o Haupapa: Moisture, the breath of Haupapa, is shrewdly placed near the Ngaru Paewhenua work, a corner projection in the next room that uses images of ice and water to comment on the disappearing Haupapa (Tasman) glacier. Via their juxtaposition the two works resonate with and enhance each other.

With MĀKŪ the ‘action’ is very slow, often frontal, and the picture-plane translucent—at times appearing to be microscopic-while in parts voices recite the names of Māori ancestors so the past is never severed from the present. We see close-ups of the melting and splitting glacier and its attendant lake: a mix of live and recorded images and sound.

The horizontal shots don’t flow onward together but occur in sudden isolation or bursts, at times unnerving with an ominous, cracking, violent soundtrack. This is because the light levels and the movement of the projected ice/water imagery—and tone of the emitted aural recordings—are affected by a live NIWA weather stream sensitive to real time solar conditions and wind direction.

The Breath of Weather Collective: Kōea O Tāwhirimātea / Weather Choir project involves eight collaborating teams invited by Phil Dadson to set up aeolian harps on coastal Pacific Ocean sites at on Niue, Rarotonga, Tonga, Samoa and Aotearoa (Parihaka, Whakatane, Tāmaki Makauru, and Haumoana). Video and audio recordings were made over one year, and much of this material can be seen/heard online. Dadson has constructed a shorter edited single-channel (looped) video of 17 minutes for the Te Tuhi space.

Phil Dadson and James McCarthy have also installed delicate spindly aeolian harps on the Te Tuhi roof to create harmonics when winds from the Tāmaki estuary get unruly. Standing outside to listen to the vibrating wires, one needs to consider wind direction, and when to avoid traffic noise or thunder.

Paul Cullen’s Weather Stations installation references an earlier version made for Waiheke Island. It is presented outside in the Te Tuhi courtyard, and inside, one early ink drawing from the seventies is shown opposite two other wash and ink studies for the nearby concrete-slabbed, glass, pipe, steel and rubber tubing structure.

Science here in this deliberately half-arsed ‘rain collecting’ sculpture is dismissed as inconsequential, without value-because of human apathy—for the displayed ‘research’ parts exude a calculated ineptness: its rubber, glass, pipe, steel and concrete components are never efficiently connected, assembled or positioned. The technician capable of resolving them and fitting the parts together to enable measurement has fled. Meteorological recording or competent functionality is impossible; the ferocious behaviour of the elements has caused it to be abandoned.

Nujoom Alghanem’s project, Field of Heat and Dust features a large coloured text-covered photograph of Aisha Al Naqbi, a woman who works by seeking out and domesticating bee nests in the wild NW mountains of the United Arab Emirates so she can bottle and sell their honey. Global warming has badly affected the number of potential hives, and so the amount of sales.

From adjacent speakers we can hear an edited soundtrack of Alghanem’s documentary film on Aisha Al Naqbi’s search, and those also of Fatima Al Naqbi and Gareeb Al Yammahi: Honey, Rain and Dust, edited by Ahmad El Habbal and with music by Mohammed Haddad. Being non-visual, it is a pretty subtle work that I suspect most visitors won’t notice.

I think there is an argument that many exhibits in this show are too subtle. They fail because of their understatement or technical complexity, being over restrained and too nuanced. If you compare this art with the real experience being caught in a catastrophic flood or terrifying gale, much of the work seems over cerebral and lacking in physical impact.

In other words, it is wanting in emotional efficacy maybe because it is art. That might be the problem, because it (the physical underwhelming limitations of art, its sites and its small audience) hampers the activism. You could argue that the money for these Te Tuhi commissions would be better given directly to Greenpeace, but no, here it is still well spent. It is crucial, art—whatever its nature, politically effective or not—receives institutional funding. Those institutions should be there to provide forums and assistance for art’s articulation, whatever its typology, be it successful at communication, or popular, or otherwise.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.