John Hurrell – 19 July, 2023

We see Rosemary Mayer's Midwinter Ghost, a moderately sized delicate sculpture made of spindly wooden rods coated with metallic paint, tied on dangling ribbons, scrunched-up and tumbling translucent and transparent paper, sometimes coated with oil pastel, and cords—positioned so the natural light from a nearby window passes through it.

Auckland

Özlem Altin, Quishile Charan, Judith Hopf, Laida Lertxundi, Rosemary Mayer

Scores for Transformation

Curated by Ruth Buchanan

24 June -18 August 2023

In Scores of Transformation, this exciting international group exhibition of five women artists, the dominant figure who serves as a hub—a central foil replenished by viewing the other ‘satellite’ four—is the little known seventies feminist New York sculptor, Rosemary Mayer (1943-2014). Of the eight items presented, about half focus on her specifically.

Overall, the show looks at ‘scores’ as time-based processes in art, alluding to musical layering, motif and structural repetition, performance sustainability, and cumulative narrative tension, built up like successive lines of poetry, slotting the contributing and contrasting texts, films, sculptures, printmaking, dyeing and collaging endeavours into part of a wider Artspace Aotearoa theme for 2023: Where does my body belong. Aware of transitional states, they collectively look at the boundaries of the predominantly female corporeal entity, and the possibilities of its attendant selfhood(s). There is even a quirky metempsychotic dimension to be seen in Hopf’s film, Hospital Bones Dance, with an actor miming Bob Dylan’s now mutilated song, ‘Like a Rolling Soul.’

Mayer’s fascination with the puffy sleaved forms of decorative garment fabrics depicted on female bodies in the fourteenth century paintings and devotional marble sculpture of Florentine Mannerism—and their link to her sculptural practice—is a major generating feature. Her lists of influences are printed on lined quarto-sized lecture paper that is blown-up wall-sized, while we see on a long stand, twenty pages from an artist’s book revealing cursively written commentary and collaged photographs based on her study tours through key art museums in Italy, France and Germany. Mayer’s written lists of influential nouns—along with research notes—provide inspirational qualities, and the exhibition artworks themselves espouse generative transitive verbs that engage hyperactive or reposed (but contorted) bodies.

We see Midwinter Ghost, a moderately sized delicate sculpture made of spindly wooden rods coated with metallic paint, tied on dangling ribbons, scrunched-up and tumbling translucent and transparent paper, sometimes coated with oil pastel, and cords—positioned so the natural light from a nearby window passes through it.

Adjacent in a small alcove is a 28 minute audio recording of a slide lecture Mayer gave c.1978, commenting on nine, very large, richly coloured, ‘drape’ fabric sculptures suspended from gallery walls or ceilings—and again discussing specific inspirational Mannerist paintings and artists like Pontormo or Bronzino who with empathy often depicted groups of women. On the central coffee table are various Mayer catalogues and an approximate transcript of the text running through the twenty artist-book pages.

From the transcript we see that Mayer came from a family deeply interested in art, Catholicism, and Italian history. From her recorded talk, we learn that some of her works are named after the admired female Greek philosopher Hypatia, the Roman empress / politician Galla Placidia, and the pioneer German playwright Hrosvithia. One other work is named after a group of ‘Catherines‘ influential in European history that includes Catherine the Great, Catherine of Sienna, and Catherine of Aragon.

This complex, serious but at times fun, show has an emphasis on spontaneity, instinct and improvisation, yet through its interest in notation and the passing on of transforming knowledge, is deeply conscious of predetermined strategies to enable bodily resistance to / subversion of controlling patriarchal systems. Vectorial components (as tropes taken from sculpture and painting) swoop, stretch, fatten and buckle as overlapping methods of art practice propel layered allusions in multiple dimensions.

In some ways, the two coloured films (by German and Spanish artists) are the superior contributions because of their immediate emotional impact. Hopf’s video is frivolously ghoulish with its hammy permutations of skeletal dancing zombies, leg-dragging mummies, hopping and limping cripples—and unhelpful hospital receptionist—while Lertxundi’s longer filmed suite of ‘therapy’ interviews (shot in California, audio in Aotearoa) is earnest, heavy and confrontational in the Godardian sense; stressing alienation or indifference, and avoiding ingratiation. Both are refreshingly compulsive: one being ‘silly’, yet viscerally addictive; the other, polemical but strangely mysterious and genuinely interesting.

Özlem Altin‘s collaged blue canvas on a blue wall, with its elongated and dismembered body parts, internal penetrations—and affinities with Ava Seymour and Nancy Spero—is conceptually connected to the final section of Lertxundi’s film where individual body parts peek through a masking yellow field. There seems to be a suggestion, in both cases, that we are mentally and physically composites of others (beyond family) and that great ideational distances can extend between the separate organs.

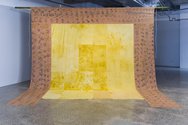

Indo-Fijian artist, Quishile Charan, has sewn together printed and dyed pillow cases for her family, layering petaled motifs and finger-agitated dyes from genda, kutch and hibiscus flowers. It is a clever idea, to create pillows that could be vehicles for dreaming. They showcase blurred handmade marks that provide ‘nests’ for the imagining reposed human head, with added (onion-skin stained) outer bands, made into suspended coverings or sheets as a statement about community. The reference to flowers echoes Mayer’s own watercolours.

The works in this show are varied, but the way they cohesively lock together is convincing as a statement about parallel creative processes. It might be argued that I have over-emphasised Mayer in this discussion, not sufficiently examining the roles of the other four contributors. That claim I would, of course, disagree with. However, you should explore this stimulating presentation yourself through direct encounter, if you wish to arrive at a more resolute conclusion. It’s an exceptionally layered, very mentally rich exhibition.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.