John Hurrell – 3 August, 2023

You can see in front of you why I have started my text in this unorthodox manner. By coincidence Denis O'Connor has included in his current Two Rooms show an image on roofing slate of a “knife,” an image that though a pencil-sharper, is conical and so also a thimble. It has several meanings.

In his 1977 book, The Modes of Modern Writing, that discusses the nature of metonymy (a figure of speech where an associated object or body part is a substitute for the name of another object, or institution or concept), the British novelist, critic and theorist David Lodge—following the pioneer linguist Roman Jakobson—once casually suggested as an example of this term (p.78) that a traumatised aphasic patient might say “pencil-sharpener, apple-parer, bread knife, knife-and-fork” instead of the more disturbing word, “knife.”

You can see in front of you why I have started my text in this unorthodox manner. By coincidence Denis O’Connor has included in his current Two Rooms show an image on roofing slate of a “knife,” an image that though a pencil-sharper, is conical and so also a thimble. It has several meanings.

His selection of wall works in the upstairs gallery (along with some sculpture) includes found pressed plants from 1883 (under glass) as themselves, and objects and animal parts painted on slate as replacements for key natural and artificial objects that he recalls within personal narratives.

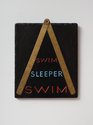

In the 14 slate paintings he presents the use of what I call ‘fake inlay’, as if using jewel-like insertions, but they are really intact surfaces with incised edges—not additions physically plugged into holes—and sometimes also flat relief carving. Metonymy emphasises a displacement, an imagistic substitution for a name. The mock inlaid image serves as kind of rebus for the written ‘naming-word’ where it is the ‘inlaid’ shape that has meaning, not the word that that shape describes.

For example, the painted blue feather in The Plumassier (The Feather Trader) does not in itself mean a question, but its curved linear shape does. An unbent avian winged body part does not alone equate with interrogation.

These paintings look like book-covers, enticing openable codices containing pages, and with text covered vertical spines (or columns of dominoes) along their lefthand edges.

Of course O’Connor is presenting single panel, static, painted and carved images here that may allude to a narrative that he could (if he wished) elucidate verbally or in a text. They are not stories, or films or comics—with sequential parts—they are puzzling symbols (constructed fake metonymies) that might also involve frozen protagonists within slices from a chronological stream.

Out of the whole show, it is these discrete slate works lined up in a row that I wish to emphasise, and not the five pieces of sculpture on the opposite side of the narrow space—though one freestanding piece, The Bowl that Waited, has many methodological (exquisite corpse?) similarities with one slate painting in particular, Kerfuffle (St Kevin and the Marginals).

Both have extra-long body parts: The skinny white sculpture with short bendy legs (attached to feet wearing turquoise jandals) shows a long undulating arm reaching upwards, holding a copper infused porcelain bowl placed on a beautiful ebony box. The colourful Kerfuffle, (St. Kevin and the Marginals), on the other hand, presents a wonky letter ‘K’, standing for Karangahape Rd.

The letter consists of a reaching out arm at the top, attached to a restless leg attached to a yellow sock and stamping boot, and an elongated spotted red toadstool fastened to a white horse’s shank. It is gorgeously evocative and seems to be a mysterious synthesis of Irish folktales and the vibrant night culture that dwells on this west-east ridge. The human, animal and fungi parts could be sequential permutations of a single shape shifter, what O’Connor calls a Mister Lucken. (See hand out interview with Emil McAvoy.)

One of my favourite works is Umu Kotuku (Nankeen Night Heron) where a small, delicate, colourful heron (recently emigrated from Australia) rests on the ticklish flat sole of a stretched up, inverted foot reaching out of a tributary running off the Whanganui River. I can almost feel its scratchy claws on my own tootsie.

Another gem is Cairn of the Hourglass, a painting that shows an egg-timer that might also be a pink toilet bowl with raised lid. In the top oval are several sliced up dice, and cascading down into the lower ‘bowl’ are black dots from the shredded cubes. Comparing chopped up numbers to falling poo is a droll way to condemn gambling and wasted money. A scatological yet witty method of saying something very serious, this is one of many treasures in a fascinating presentation.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.