John Hurrell – 2 November, 2023

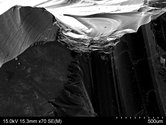

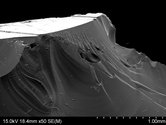

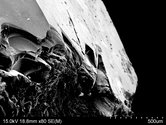

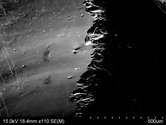

The landscape feel of these evocative, 30 sec long images makes the human viewer seem minute, and the gazed-on 'vistas' panoramic and sublime. You appear to take on the eye of God, hovering high in space—looking up as well as down, during day as well as night, perhaps in the future as well as past. Glowing and transient flashing light is caught on the small ridges and specks of the striated obsidian surfaces, and within their highly absorbent textured, flaked and pockmarked forms.

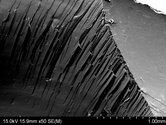

This very beautiful, forty minute video at Starkwhite, from Clinton Watkins, features a long sequence of slow moving ‘vistas’ that seem to play off mineral geologies, impasto paint close-ups, night skies, and mountainous snowfields-ambiguously all at once, separately, or in pairs—being totally mesmerizing in piercing black and white. Some are repeated and sequences might be shuffled around.

Seen frontally or from oblique angles, these mysterious images are not double exposed, Photoshopped or collaged. In fact, these photographs are of reflective shards of black obsidian, made with an electron microscope (that normally we associate with images of tiny insect parts)—scanned, greatly enlarged and cropped.

The landscape feel of these evocative, 30 sec long images makes the human viewer seem minute, and the gazed-on ‘vistas’ panoramic and sublime. You appear to take on the eye of God, hovering high in space—looking up as well as down, during day as well as night, perhaps in the future as well as past. Glowing and transient flashing light is caught on the small ridges and specks of the striated obsidian surfaces, and within their highly absorbent textured, flaked and pockmarked forms.

It is extraordinary how the apparently ordinary geological samples that Watkins has picked are magically transmuted into steep mountainous terrain, or apparent brushloads of hardened thick oily paint, fields of stars, or sparkling blankets of crusty snow, while a distant rumbling from an added soundtrack, gradually crawls its way into your ears.

Watkins’ exhibition notes on the SW website emphasise the geological processes of obsidian’s igneous formation, and the component of silica within its volcanic mineralogy. The rock’s glasslike brittleness exploits the impact of reflected light, a crucial contributor to the success of these dazzling images.

Apart from briefly mentioning landscapes, Watkins does not try to guide interpretations of his arresting photographs—or even expand on how such interpretations exist—only explain the mineralogical origins of what is placed in front of the electron microscope. With these geological processes, it is possible he intends a metaphor to do with the ideational crucible of the creative occurrence, comparing the artist to the forces of nature.

Whatever the case, experiencing these detailed textured ‘landscapes’ (that seem at high altitude to be accompanied by unnervingly clear air) suggests many dramatic possibilities of how to see them and the implied spaces they contain. As glorious fantasies, they are an extraordinarily imaginative micro-to-macro transition.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.