John Hurrell – 6 July, 2009

So when Luit and Jan Bieringa’s film about him was announced as being included in this year’s International Film Festival, there was considerable excitement. Yet my impression after seeing it is that it is a bit of fizzer.

The Man in the Hat

Directed by Luit Bieringa

Produced by Jan Bieringa

Photography by Leon Narbey

73 minutes

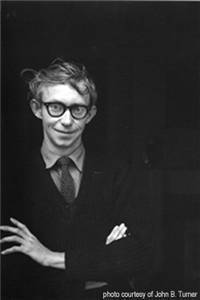

There must surely be no more revered contemporary art personality living in this country than the historically pivotal art dealer, Peter McLeavey. There has been some brilliant journalism about him and his hugely significant contribution to our visual culture (by Bryan Staff, Grant Smithies and others) but so far - until this year - no movie documentation. So when Luit and Jan Bieringa’s film about him was announced as being included in this year’s International Film Festival, there was considerable excitement. Yet my impression after seeing it is that it is a bit of fizzer. Lovely to hear the man talk, but as art docos go, not as appalling as Merata Mita’s , but nowhere near as good as Leanne Pooley’s Being Billy Apple or Judy Rymer’s Victory Over Death. Just so so.

So what went wrong? Why wasn’t it as good as those last two? With the co-operation of a tirelessly loquacious, charismatic personality like McLeavey, and an esteemed cinematographer like Leon Narbey it should have been superb. Why wasn’t it?

First of all only three days were spent filming. Somebody like McLeavey, whom everyone knows is a complex individual, will always tell great stories (even to strangers) about his childhood, family and friendships with certain key artists - but that is just the surface. He needs to be gently prodded so that he is continually recorded at length to make a substantial document. Something over a couple of hours with real depth. He is so engaging he is always watchable.

There are many unpresented questions that could have been asked: I’d like to know what was it like to fill a Morris Minor up with paintings (as I’ve heard he used to do in the sixties) to take them to motel rooms in distant cities to try and sell them? Why and how did he persuade Woollaston to make the wonderful panoramic landscapes? Where did he learn to become a salesman? Did he ever consider that the role of spiritual themes might be over-rated in this country? Why did Hammond’s prices go up after the Auckland Island trip and not before? (What was it about the imagery?) Why did he get upset with L. Budd ‘blonding’ his chaise longue? And most importantly, when did he start wearing a hat? The McLeavey brand is actually his silvery (Warholesque) hair, his round ruddy (babylike) face, and those alert blue eyes behind stylish glasses. Always instantly recognisable. No hat.

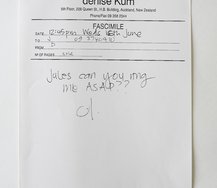

Much of the film, as you’d expect, is fascinating, especially when our subject is talking about his nomadic childhood, his Catholic education, Freudian psycho-therapy and his bouts of depression. Or his passionate collecting of internationally sourced photography or publications of New Zealand poetry. The excerpts of letters from or to him from McCahon, Woollaston and Walters are the highlights.

The film’s photography though is disappointing. Some of the interviews were held when he was slumped in a chair and filmed from below, making him look facially a bit squat or froglike. He should have been filmed at eye height. After all, he is a salesman of infinite persuasion and charm, a great communicator who is very expressive and direct. Show him as he is normally seen.

Furthermore, in this film too much is made of Wellington and its inhabitants. McLeavey, perceived by many as a national treasure, is admired everywhere in this country and beyond, but Bieringa, in my view, wastes too much time showing life on the streets of the capital, and his subject’s daily wanderings between home and gallery. Such subject matter is consistent with Bieringa’s earlier film on Ans Westra, and as director it is natural he follow his own creative humanistic impulses - though his agenda is not overbearing to the cost of his subject as Mita’s was in her Hotere. Yet despite his comparative restraint, for documenting such a significant player in our visual heritage it is regrettable that he did not play ‘David Sylvester’ to McLeavey’s ‘Francis Bacon,’ and develop some extended, really pithy conversations over three whole months, instead of only three short days.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.