John Hurrell – 27 July, 2009

The detailed research poured into this publication impresses and the (usually Marxist) writers are shrewdly picked for their different areas of focus.

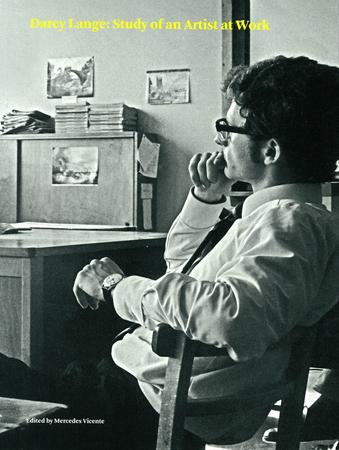

Darcy Lange: Study of an Artist at Work

Edited by Mercedes Vicente, with contributions by Benjamin Buchloh, Guy Brett, Lawrence McDonald, John Miller, Geraldene Peters, Pedro Romero, Dan Graham and Mercedes Vicente.

Softcover, 208 pp. b/w and colour illustrations

Published by Ikon, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery 2008

New Zealand’s pioneer video documenter of working life, Darcy Lange (1946-2005), was often included in small group surveys of seventies practice, exhibtions that usually ended up with skimpy catalogues. He now has a substantial document about his projects, a publication that accompanies the New Zealand show (organised by Mercedes Vicente, the Govett-Brewster’s curator) presented at the Govett-Brewster and Adam Art Galleries, and the English version (curated by Helen Legg and Mercedes Vicente) at the Ikon in Birmingham. The achievement of Vicente, its editor, is that she has managed to rustle up an amazing group of authorative scholars, curators and artist /friends from around the world to contribute a suite of varied but highly informative, accessible essays; all about an artist whose videos - being in real time and unedited - many in the art world consider unwatchable. The detailed research poured into this publication impresses and the (usually Marxist) writers are shrewdly picked for their different areas of focus.

Vicente’s own essay is a comprehensive biographical and historical overview of Lange’s work in Spain, the U.K. and Aotearoa that sets up a thorough introductory context for the endeavours of the other contributors. In the preceding but illuminating preface she tells us a little about her own Spanish background and what attracted her to Lange’s work, introducing the notion that his performances as a flamenco musician were an extension of his video practice.

October co-editor, Benjamin Buchloh, is an art historian who always has a forthright point of view. His immensely interesting essay is about the history of documentary photography, in particular the period of the mid-seventies when certain ‘progressive’ artists such as Burgin, Wall, Roster and Sekula began through their practice to criticise conceptualist photography because of its prohibition against referentiality and representation and emphasis on deskilling - and open up an interest in particular historical, social and political conditions. The artists they reacted against - Ruscha, Graham, Huebler, Baldesarri and Smithson, sometimes were their friends, as was Graham with Lange - for Buchloh subtly aligns Lange to the critiquing group (though he is very different in not having an interest in theory, as Vicente points out) because of his ‘recovery of the working body’, his ‘persistent interest in the conditions of social class’, and his recognition of ‘the universal permeation and presence of skills in every member of the working collectivity.’ (p.60)

Lawrence McDonald extends this side of Lange’s thought when he points out that Lange considered Polynesians to do “everything as creatively as they can”, and that “creativity in schools is not necessarily confined to the art class (p.124)”. Much of McDonald’s discussion in a superbly researched essay is taken up with the ideas of education theorist Paul Willis that he posits as parallel to Lange’s methodology. He refers to two of Willis’s books, the first being The Ethnographic Imagination (2000) which asks “..what are the consequences of viewing everyday relations as if they contained a creativity of the same order as that held to be self-evidently part of what we call the arts?”

The second Willis book, Learning To Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs (1980), McDonald spends more time on - firstly in connection with Lange’s interest in middle class subjects in the UK (unlike say the New Zealand working class projects), and secondly in Lange’s move going beyond the observational to the more interactive. He and Guy Brett both write about Lange’s possibly most important project, Work Studies in Schools (1976-7), a documentation of teaching in Birmingham and Oxfordshire - important because of Lange’s process of showing his videos to the teachers and pupils later so they could separately assess their performances and behaviour (while being filmed). Intriguingly, Brett compares this work to Dan Graham’s transparent / reflective mirrored pavilions and Oiticica’s hammocks for sound and projected collages where social solitude and social interchange were fused.

McDonald is interested in the dialogical aspect of these Work Studies, how someone like Willis (who used transcribed audiotapes for his book) or Karl Heider (with his related publication Ethnographic Film [1976]) might analyse them. He points out that Lange blended his observational data collection into the interpretative process, that there was no editing or selection process separating the two - or devices like voice-over commentary, written titling or sound design. Only long takes, uninterrupted real time, and the unfolding of social processes which the viewer can work at to analyse if they wish.

Ngapuhi land rights activist John Miller, a friend and collaborator of Lange’s, with Media Studies lecturer Geraldene Peters writes a thorough account of his Maori Land Project (1977-80) a set of documentaries examining the Ngatihine Block and Bastion Point land claim disputes, of which a short 25 min version was shown on Dutch television in 1980 (but without Maori participation in the editing - due to travel funding difficulties). Miller and Peters’ impressively detailed account also covers some of the early eighties, and in it you get a sense of Lange’s personality and life style, his characteristic traits while working - such as his restless energy and political commitment, an ad hoc interview style, the fragmented, ongoing, unfinished nature of many of his projects and his financial hardships.

Pedro G. Romero’s contribution is the biggest surprise of the publication. It folds Lange’s musical passions into the fabric of his video documentations. In particular he elaborates on Lange’s flamenco discipleship of the legendary Diego del Gastor, and amusingly (as a touch of authorial wish-fulfilment) makes comparisons between certain guitar styles and Lange’s camera rhythms (p.172-3). He also points out the tragedy of Lange’s failure to complete a proposed Art of Flamenco As Work as a form of resistance to the commercial banalisation of consumer culture.

Dan Graham’s contribution about his friendship with Lange is brief but moving, and works well with the commentaries by Brett, Vicente, Romero and Buchloch that spasmodically allude to similarities and oppositions between the two artists.

This diverse set of writers clearly see Lange as using video as a means of social activism, yet whilst his imagery is loaded with historical, technological and political information about the seventies, and intimately connected to the different communities he worked with, it is hard to imagine contemporary audiences showing much empathy for its real time methodology, even when displayed in sophisticated gallery installations. However while I’m thus not sure about the efficacy of Lange’s practice as strategy (does it provide more than what any observant person would see walking round a city watching working people; or is it really about fetishizing video as a medium?) I did find this book an informative, thoughtful and very pleasurable read. Well designed and easy to scan (its font doesn’t make readers over forty have to squint) and packed with surprises, it deserves a wide international readership.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.