John Hurrell – 20 August, 2010

Instead of a self-perpetuating CV, consider the cleverness of Baldessari's 1966-8 A painting That Is Its Own Documentation, where the writing on the canvas sets out its own exhibition history. Dashper's CV work is too literal in its translation of Baldessari. Like his paid-for ‘review' ad in Artforum, and the depicted slide sets serving as artworks, it ends up a trivial gimmick.

It is a little over a year since Julian Dashper died and this show is a compact survey put together by Ariane Craig-Smith, a freelance curator who at one time was one of his students. The tragedy of his premature death at 49 makes it difficult to assess his life’s work unemotionally, but this Gus Fisher show gives us the chance to look at its qualities or failings - if qualities or failings it has.

‘Conceptual art’ as a term has long been over-used, and even within a certain specific time period (mid-sixties to mid-seventies) practices that once were lumped together as ‘Conceptual’ are now being pried apart - often at the instigation of the artists, not art historians. And the very term, Conceptual Art, might be considered a laughable tautology, though perhaps it also might be seen as a separately bracketed concept within a concept.

This show is called Professional Practice, named after a course Dashper set up at Unitec with Richard Fahey for painters who were lumbered with a typography course. Now typography might have been valuable for such students (Billy Apple I imagine might claim that) but Dashper felt there was a need to elucidate various procedures within an art practice that he saw as essential to enable furthering a successful artist’s career.

So to be a professional artist, what does that involve? Are artists the priests of some sort of secular cult, embedding ‘art’ values in mainstream culture, so that professional practice ends up being a kind of ‘theological’ course aimed at perpetuating art by proselytising. Or is the relationship implied between art and mainstream culture there inaccurate? Does the notion of ‘professional’ art values have legitimate currency?

If I have a problem with Dashper’s notion of Professional Practice it is because I think he was an unabashed believer - the work confirms it, and its hermetic worshipful titles about other artists - and that worries me. He was not sufficiently critical of the community of which he was a vital part, and I see that as a problem. New Zealand’s art world needs more artist-critics like for example David Cauchi and Roger Boyce, individuals who spot-light through their easily-grasped work the sort of ethos conventional ‘art professionalism’ represents. Using laughter, they raise questions about art cultism - something that Dashper strived hard to perpetuate.

Okay, let’s now zero in on works in the show. Some I admire. Others I don’t.

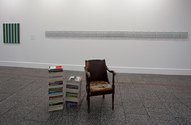

Two works which exude a pomposity that I loathe are Untitled (CV) (1995-2009) and What I am Reading at the Moment (1992), the latter being a high stack of Artforums alongside a chair. Others might claim they are about innovative content but I think they are about vanity. Dashper put on long term loan at Waikato Museum of Art and History another far superior version of Reading where the magazines were laid out as a kind of Carl Andre carpet on which the chair was placed. That sculpture was witty, and about epistemological foundations. Far more brilliant than the one now at Gus Fisher.

The counter-argument to this sculpture is John Baldessari’s 1968 painting with a screened-on photo of an artforum cover, under which is written This is not to be looked at. It scoffs at any fawning towards international art magazines, encouraging artists to think for themselves and be independent of so-called ‘authorities’ of taste.

And in terms of wit, instead of a self-perpetuating CV, consider the cleverness of Baldessari’s 1966-8 A painting That Is Its Own Documentation, where the writing on the canvas sets out its own exhibition history. Dashper’s CV work is too literal in its translation of Baldessari. Like his paid-for ‘review’ ad in Artforum, and the depicted slide sets serving as artworks, it ends up a trivial gimmick. These last two - though about distance - don’t really help serious discussion about Aotearoa New Zealand’s isolation, despite Dashper’s claims. They are more about an artist’s ego and exhibitionism.

For all my dismissals there is a lot of work here that is terrific. I like the fact that Ben Curnow has to be sitting at the large desk in the main gallery for Untitled (Portrait of Ben Curnow) 2004 to exist - to be complete. That the creases on Untitled (O) 1990-92 from its folding for easy portability to easy to detect. That the six sound recordings made from Pollock’s Blue Poles effectively showcase the enigma and transcendence of presence. That the vinyl-on-drumskin and painted velvet Regent works look so sexy.

Some works that used to irritate, have now won me over. I remember seeing the five watches of The Big Band Theory on display in 1993 in Tina Barton’s Art Now biennale in the old National Gallery, with their names (The McCahons, The Drivers, The Hoteres, The Woollastons and The Anguses) separately on each dial, and being extremely annoyed because the work seemed more about inane Hollywood TV celebrity (like say The Monkees) than serious art. It trivialised. However in view of their link with the various drum-kit works and Dashper’s notion of cultural ‘timekeepers’ I can see now they weren’t in isolation but part of a larger project.

There are several works I would really have liked to have seen here: the wooden stretchers that Dashper showed with Simon Ingram and Salvatore Panetteri two years ago at Newcall; other ‘stacked’ facing-the-wall stretchers that Natasha Conland presented in a recent AAG collections exhibition; the morphine paintings; some documentation of Future Call, the work where he phoned a small village from Italy from an ‘earlier’ time zone; the uncharacteristically Tindallesque sociological golden chains and linked frames - but hey, there is so much stuff out there it is nigh impossible. All to be looked at closely and evaluated. With this survey the Gus Fisher and Ariane Craig-Smith have done us all a big favour, putting together a stimulating catalyst to get people thinking.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

The great John Baldessari has left us. It is hard to think of any other contemporary artist more loved by ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 8:53 a.m. 7 January, 2020 #

The great John Baldessari has left us. It is hard to think of any other contemporary artist more loved by successive generations. As teacher and brilliant conceptualist, he will be hugely missed.

https://fontsinuse.com/uses/30283/learn-to-dream-by-john-baldessari

http://eyecontactartforum.blogspot.com/2008/07/baldessari-billboard.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/05/arts/john-baldessari-dead.html

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.