Will Gresson – 21 February, 2013

Ultimately the success of the show lies in its ability to extend beyond the science and bring things back to relatable human feelings. While other shows currently showing in the German capital seem to only revel in the ‘newness' of the technology which they address, LEAP's exhibition goes that one crucial step further in prioritising the sense of relation.

LEAP (Lab for Electronic Arts and Performance) is a collaborative project put together by Daniel Franke, Kai Kreuzmüller and John McKiernan which seeks to draw lines between art, technology and science. It is a few years old now, and since inception they have hosted semi regular performance events such as the Body Control series alongside exhibitions and installations at their space near Alexanderplatz, in an otherwise unattractive, kitsch and very touristy part of the city.

Their latest exhibition, Abstrakte Welten Realisieren (Abstract Worlds Realised) seems to perfectly embody the aspirations of the mission statement on their website .The four installations which make up the show are all equal parts science experiment and sculpture; what stands out after viewing them however is how strangely easy it feels to relate to them. The same day I saw this show I also went to an exhibition as part of the massive Club Transmedial Festival, the themes of which also concerned the cross-section of music, art and science. The effect of this latter show was totally alienating, however where this project failed LEAP’s latest show succeeds wonderfully.

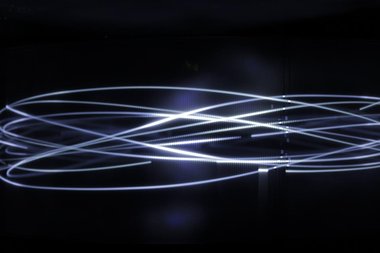

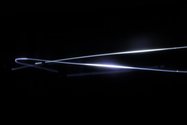

The first installation which must be walked past in order to reach the rest of the show is Markus Hoffmann and Lucas Buschfeld’s piece Aloop. Using a Geiger counter as a measuring sensor, the installation reads the radiation level in the space (taking into account the spectator as well as changes in the surrounding area of the gallery itself) and emits small bleeps which became flashes of light at either end of a spinning line. The room is in pitch black, and so the spinning line creates streams of light which spin around the centre. Despite being a difficult work to describe, its effect is simple and powerful. As the measure of radiation in the room is never constant, the corresponding light show is always different too. The longer you stay in the room, the more your eyes become accustomed to the light, registering it as single beams rather than two points spinning. It feels like a lot to digest to examine the mechanics of Aloop, but the triumph of the work is its sheer beauty and simplicity when experienced in the flesh.

As you pass through into the rest of the show, the second work you encounter is Verena Friedrich’s piece Transducers, a collection of small glass tubes all containing a single human hair. Each hair is ‘triggered’ by the surrounding machinery, creating a small audio output. As each hair is different so too is each sound slightly different, a tangible, sonic register of each unique human specimen. Its low hum almost seems akin to the sound of an old light bulb buzzing, which in the context of the works shape and dimensions, and the somewhat ramshackle space in which it sits feels fantastically fitting.

Yesterdays Today (The Supertask), created by Sascha Pohflepp and Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, takes its name from British philosopher James F. Thomson’s name for ‘a quantifiably impossible endeavour.’ The work addresses the notion of creating models, more specifically in this case the weather. While a large light work on the wall reduces the world to a single digit temperature reading in degrees Celsius, a small box of wood and plastic sheeting creates an isolated chamber where visitors can step inside and experience a different weather model from that outside. This playing with space is an interesting idea, though the computational work underpinning the work is some of the hardest to come to grips with. While the things going on behind the scenes may be less easy to grasp than other works in the show, purely on a visual level the installation is still engaging.

The final work in the show, and by far my favourite is David Bowen’s Tele-Present Wind. The installation consists of 42 small devices, each with a dried plant stalk sticking up from them. Using an accelerometer positioned outside, the stalks move and sway in accordance with wind conditions measured outside. For the purposes of the show at LEAP, the sensor is ‘installed adjacent to the Visualisation and Digital Imaging Lab at the University of Minnesota,’ so in effect the devices in Berlin are actually responding to weather conditions measured and transmitted from halfway across the world. While the science of this is certainly interesting, raising notions of time and place, distance and environment, on purely visual terms it is also an incredibly beautiful work. The movements create a real sense of place, even with the obviously technological constructions apparent in the whole process, and to stand amongst the stalks as they move is quite something.

Ultimately the success of the show lies in its ability to extend beyond the science and bring things back to relatable human feelings. While other shows currently showing in the German capital seem to only revel in the ‘newness’ of the technology which they address, LEAP’s exhibition goes that one crucial step further in prioritising the sense of relation. It’s this which is the collection of works’ most lingering impression.

Will Gresson

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.