Warren Feeney – 10 January, 2014

In terms of audience development, the Canterbury Museum made an excellent decision to act as centre for this event. Rise invites comparison with strategies undertaken by the Auckland Museum in 2007 when it curated the exhibition Loli Pop a downtown Auckland view of Japanese Fashion, which sought to address the lack of participation in the Museum's programme of an increasing Japanese population in Auckland.

Christchurch

Local and international street artists

Rise Festival

Street Art: Rise Festival and From the Ground Up Project: Askew, Beastman, Berst1, BMD, Daekwilliam, Deus, Diva, Drypnz, DTR, Eno, Fat, Fluro, Ghstie, Jonny Higher, Anthony Lister, Misery, Morepork, Oche, Paulie, Phat1, Rita V, Roa, Rone, Gary Siupa, Sulk, TMD, Vans the Omega, Wongi and Ikarus, Yikes. (Canterbury Museum and various inner city locations)

Oi You! Collection: Banksy Collection, and work by Buff Monster, Cheryl Dunn, David Choe, Faile, Adam Neate, Antony Micallef, Milton Springsteen and Swoon. (Canterbury Museum)

Ian Strange, Final Act (Canterbury Museum)

20 December 2013 - 23 March 2014

Have the visual arts in Christchurch ever received the degree of popular attention and media coverage that the Rise Festival of street art had currently generated? Possibly only the touring exhibition in 1906 of Pre-Raphaelite painter, William Holman Hunt’s, The Light of the World, has met with a similar level of publicity and interest. Like Hunt’s image of the despondent Christ, Rise has been featured in the local media virtually every day since it opened on 20 December 2013.

Encompassing the work of more than forty New Zealand, Australian, British and American artists, Rise aims to be a ‘celebration of street art’ but for many in Christchurch it also represents an introduction to an art form that has been slow to gain credibility in the city, in spite of its presence throughout the east side for the past thirty years. So, the attention street art is currently accorded raises the question; why now? This was an issue that formed the subject of a recent Press editorial. The column, ‘Street art brings colour to city‘, followed three front page photographs in the newspaper over a period eight days and the editorial was fulsome in its praise, in spite of drawing attention to street art’s ‘genesis in the scourge of graffiti.’ The Rise Festival is also worth taking notice of due to the number and range of artists exhibiting their work in public spaces and the Canterbury Museum‘s galleries. All aspects of the programme provide an opportunity to consider the current state and status of street art.

What is Rise‘s programme made up of? In association with the From the Ground Up Project, Rise comprises more than thirty public art works sited throughout the inner city from Sydenham to the Canterbury Museum, and the CPIT Madras Street campus to Oxford Terrace. These large-scale murals are complemented by Oi You! Collection, an exhibition in the Canterbury Museum of twenty-two works by Banksy and additional prints, paintings and sculptures by artists from the United States and Great Britain. The Museum’s exhibitions also includes Final Act, an installation, video, and photographs by Australian-born artist Ian Strange and Corrupt Classics, a series of paintings by New Zealand artist Milton Springsteen.

Did it really take a natural disaster of an unprecedented scale in New Zealand to shift Christchurch’s attention to the credibility of street art? The answer is yes. The attention accorded to the visual arts has been characterised by supportive commentaries from the Christchurch City Council, national and local media and businesses. Canterbury Employers’ Chamber of Commerce chief executive Peter Townsend has stated “Putting street art in significant [public] places…. can create a real point of difference for a city,’ while Deputy Mayor Vicki Buck rallied at the opening of Rise, that Christchurch needs more art like this throughout the city. Curator of the festival, George Shaw hopes to transform Christchurch into the ‘street art capital of the southern hemisphere,’ maintaining that Rise represents an ‘opportunity for this city to create a new identity for itself.’ And The Press‘ list of ‘try something different’ activities in the New Year, recommended: ‘Visit an art exhibition. It doesn’t have to be highbrow. You can tick this one off the list this week at the Canterbury Museum’s Banksy exhibition.’

Of course, implicit in this statement is the subtext that for the majority of the city’s population - the arts remain essentially elitist. Certainly, Rise has attracted attention because it is a user-friendly, accessible arts event. In the large scale, intensity of colour and graphic/figurative nature of the majority of works, many of the participating artists seem self-conscious of their anticipated role to brighten up the appearance of the city. Rise appears to represent a congenial partnership between its organisers and artists, community and business. All have found a means to fulfil one another’s purpose as increasing concerns about the slowness of the rebuild and the completion of anchor projects in the inner city become more apparent. The seemingly infinite number of vacant sites and buildings with exposed blank walls, all confirm that there could not be a better strategy for a sense of recovery and progress than the premise of physically brightening up the city. (And in doing so, occupying it with a more than welcome, visible human presence).

Yet, on another level, it would also be difficult to describe the majority of public art works as overly site-specific or immediately responsive to the current state of the environment of Christchurch. Although addressing the desire and need to animate the central city, many of the works confirm the pervasive global nature of street art - its international iconography/graphics, materials and methods. (But then - to be fair - it shares this criticism with much current arts practice in New Zealand). The success of the public artworks in Rise, consistently depends on their scale and technical skill. That is, artists may be working on a blank wall, but it is a surface that occupies a similar role to the empty canvas in the studio. Both await the subjectivity, skills and processes of the artist’s response. Accordingly, only a small number of the participating artists in Rise, give due attention to the specific situation of a building - its architecture, spaces, surfaces, surrounding environment and location. The iconography of Vans the Omega and Beastman on the wall of Underground Coffee in Sydenham, Ghstie’s 70s-inspired design on the YMCA’s wall, or Rone’s youthful female figure at 109 Worcester Street could be on any site in any street in any city in the world. (In contrast, however, it must also be noted that Vans the Omega’s abstract design on the CPIT building on Madras Street is responsive and empathetic to the space it occupies.)

Moreover, the scale of the opportunity to decorate the inner city with large murals like those in Rise is, in part, measured by the reality that - even with more than thirty artworks completed - the demolition process still retain a commanding authority. Which works provide the rebuild with some serious competition? From a significant distance of more than one block away, DMB’s trompe L’oeil mural on Cashel Street certainly does, and also Berst 1’s animated psychedelic image (capturing something of the spirit of the late Martin Sharp’s 1968 LP cover design for Cream’s Wheel’s of Fire) on the wall at 53 Battersea Street in Sydenham.

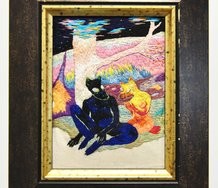

Belgium artist, Roa’s mural on the North side of the Canterbury Museum is also a highlight. A large moa skeleton and kiwi, executed in tones of grey in accord with the Museum’s concrete wall, it references something of the activity taking place inside the building and the rationale of the institution. Similarly, the painterly gestures of Australian artist, Anthony Lister’s mural by the Les Mill’s centre in Cashel Street also deals to its site. (Lister has painted almost everything within reach: the wall, shrubs, security camera and asphalt.) An additional work by Lister, is also of interest. An abstracted mix of rhythms and circular forms, located near the corner of Lichfield and Madras Street, the artist picks up on the patina of this vacant site - its colour and surfaces - all inform this work.

In addition to works by Banksy, the Oi You Collection in the Canterbury Museum includes prints and paintings by artist such as Antony Micallef, Buff Monster and Faile, from the private collection of George Shaw and Shannon Webster. The collection was displayed in Adelaide in 2013 and Nelson in 2011 and it documents the alter-ego, commercial enterprise of street art as respectable commodity and status symbol - part of its history that goes back to the mid-1980s and artists like Keith Haring.

Banksy’s images and messages are easily the most succinct in their combination of words and pictures. Kate Moss, La Applause, Flower Thrower (Love is in the Air), Barcode or Bomb Hugger are refined and convincing works. If Banksy’s art is open to criticism, it is the extent to which his social and political messages have any genuine influence on the subjects they critique. Many of his targets seem like world-weary straw dogs; freedom from capitalism, the codification of objects and products for human consumption, or Royalty as suppressor of the masses. Many of these works seem more like a panacea than a call to arms, in spite of the evidence they provide about the authority of images - even in the 21st century - as a powerful means of mass communication.

Also making up the Oi You! Collection are Springsteen’s series of paintings, Corrupt Classics. Springsteen reworks the canon of the country’s art as a ‘that was then, this is now’ moment, reinventing, (for example), William Sutton’s Dry September as Bogan Creek, with graffiti on the bridge sign, masking out ‘Bruce Creek,’ and road vehicles in the riverbed. Orchestrated over a series of well-known paintings, (He also appropriates Rita Angus’ Cass), it is an idea centred upon shifting perceptions about national identity and ‘fine art.’ Yet, in doing so, Springsteen also raises the dilemma of where his art sits within such traditional notions of high and low art.

The Oi You! Collection includes Antony Micallef’s Bomber Girl, an iconic image that reside uneasily somewhere between Rorschach blot-test and political protest. Brooklyn artist, Faile’s images are equally not entirely sure of their intentions, seemingly overwhelmed at times by the source material of the adult comic books they seek ownership of. Los Angeles artist, Buff Monster’s Untitled (2007) however, is far more certain. Pink and reductive in content, it gets close to the elegance and energy of Banksy. It also raises the question; why does a group show that introduces international street art to the gallery not include artists more well-suited to such spaces? For example: Shepard Fairey or Invader?

If Rise sought to extend thinking about what street art is, then the inclusion of Final Act - an installation by Australian-born artist Ian Strange of sections of houses from the Red Zone of Avonside, segmented and reconfigured as sculptural objects, photographs and video, is a success. Strange has filmed and lit these houses from inside and outside. The video plays like a homage to Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural sculptures and a scene from a David Lynch movie, panning slowly and circling around its subject. These houses from the Red Zone assume a personality and life of their own as creatures detached from even the most remote of experiences of domesticity.

Praised for its potential to bring Christchurch’s inner city back to life, the Rise Festival has gone some way towards doing so. In addition to daily media coverage, Canterbury Museum has commented that, even after only three weeks of opening, the exhibition has proved to be one of the most popular in its history. The participating artists in Rise have delivered Christchurch a unique arts experience and provided residents and visitors with good reason to revisit the city.

And in terms of audience development, the Canterbury Museum made an excellent decision to act as centre for this event. Rise invites comparison with strategies undertaken by the Auckland Museum in 2007 when it curated the exhibition Loli Pop a downtown Auckland view of Japanese Fashion, which sought to address the lack of participation in the Museum’s programme of an increasing Japanese population in Auckland. Rise has the potential to encourage new, and younger audiences into one of the city’s oldest institutions and to give due attention to the culture and ideologies of one of its communities that has previously been too readily ignored.

Will Christchurch become the destination for street art in the Southern Hemisphere? It will not happen simply because its inner city currently has numerous large blank walls. A commitment to an annual street art festival requires the support of local businesses and administrative bodies, alongside long-term policies and strategies for the arts. While Melbourne is considered a centre for street artists, to follow such an example, Christchurch must currently consider whether it still wishes to be as enthused ten years from now, as it currently appears to be, about advocating and supporting a visual arts project such as Rise.

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Got it sorted.

John Hurrell

Thanks Jesse. If you tell me which of the two 'Lister' works is mislabelled, I'll correct it.

Jesse Bowling

Hi I have noticed that you have named a wall by DRYPNZ in your photos as by Anthony Lister! Might ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Jesse Bowling, 10:45 p.m. 3 February, 2014 #

Hi I have noticed that you have named a wall by DRYPNZ in your photos as by Anthony Lister! Might want change that!

John Hurrell, 9:16 a.m. 5 February, 2014 #

Thanks Jesse. If you tell me which of the two 'Lister' works is mislabelled, I'll correct it.

John Hurrell, 5:33 p.m. 7 February, 2014 #

Got it sorted.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.