Warren Feeney – 19 September, 2014

In 'I see Art Everywhere', revelations and commentary about the current status of the New Zealand artist and Darragh's practice read as more than a reiteration of socialist principles or an expression of where Darragh is positioned in the country's art. There is a complex layering of scenarios and ideologies that opens up broader considerations, allowing her to maintain a balance between critical frankness and opinion.

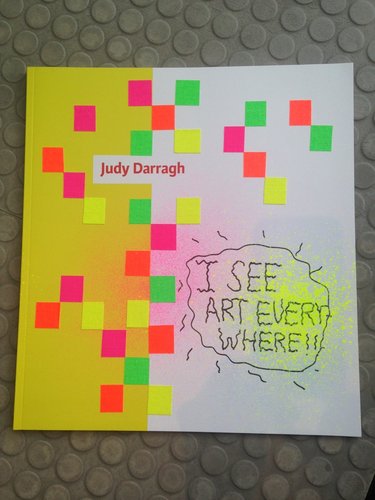

Judy Darragh

I See Art Everywhere

Judy Darragh in conversation with Tessa Laird

Essays by Louise Menzies and Megan Dunn

Designed by Fiona Gilmore

Edition of 300, each cover unique

Softback, full colour illustrations, 48 pages.

New Books, Auckland, 2013

RRP $39

It is difficult to think of another publication on a New Zealand artist quite like Judy Darragh’s I see Art Everywhere. Offering an insight into her principles and practice it also widens attention to issues around the cultural, social and political infrastructures that artists currently operate within. It is sustained by a glare-in-the-headlights openness that is absent from the curatorial agendas, art history essays and arts criticism that more typically inform this country’s commentary on the arts and its artists.

For example: What precedent exists for a critique of our arts infrastructures and the delivery of their services? Darragh’s observations on the largess of our institutions points to a void between vision and outcomes. In conversation with Tessa Laird, she comments that it is “strange as a worker/producer [of art], I am not paid to produce but managers of art workers are remunerated.” Darragh’s observations about the ways in which artists are valued or otherwise is also alluded to in an essay by Megan Dunn. ‘Submerging Artist,’ pointing out that most students currently at art school “concocting installations out of beer cans and aluminum doors… will in time no longer be practicing artists. So what? Life’s tough. Get a haircut and get a real job.”

As the introduction to I See Art Everywhere, Dunn provides the right mix of candour and self-depreciation, unraveling memories of her four years as a student at the Elam School of Fine Art in the mid-1990s that could be a confessional monologue - but consistently resists the temptation. There may be admissions about sins from the past, an indifference to the advice of tutors, the failure of others to live up to her expectations, but ‘Submerging Artists’ never descends to sentiment. Rather, its measured understatement gets to the heart of an abyss between expectations, promises and reality. Dunn makes tangible the mundane practicalities of life as an aspiring artist: “Our education as artists seems to be about redundancy at some fundamental level.”

If Dunn deals with the dubious prospects of a future for arts students, Louise Menzies’ contributing essay to I See Art Everywhere implies that the failed actuality of promises may be one of art school’s most valuable lessons. ‘It was Hot in Peace Square’ reads as a series of fluctuating notes from a diary recording the artist’s visit to the site of the 1958 Brussels World Fair. Menzies outlines her interest in the restoration of the Atomium Construction, the central building for a post-war fair that championed the virtues of atomic energy during the American/USSR Cold war. Joining the oblique associations between a visit to the gym, self-inflicted pain, Bauhaus architecture, uranium from Belgium, and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Menzies notes that walking back from the Atomium site she came across a “bright green parrot,” later discovering that parakeets had been exhibited in one of the fair’s pavilions and set free at the end. She comments: “The parakeets seem too bright for Brussels. But sometimes things are better when they appear out of place.”

The parakeets’ displacement represents an appropriate introduction to ‘artWORK IT. Community service - a conversation between Tessa Laird and Judy Darragh.’ It is a discussion, not so much about specific works by Darragh, but principles, philosophies, materials and the making of works of art. Laird remarks that Darragh’s predilections for works that often represent a collection of objects is indicative of the “sociability” of her relationships with the world at large. Darragh extends these thoughts, noting that the making of art shares much in common with the language of social engagement - “organizing and unifying the mass and masses.” A collective practice that in Darragh’s art coalesces the aesthetic, conceptual, political and environmental.

In I see Art Everywhere, revelations and commentary about the current status of the New Zealand artist and Darragh’s practice read as more than a reiteration of socialist principles or an expression of where Darragh is positioned in the country’s art. There is a complex layering of scenarios and ideologies that opens up broader considerations, allowing her to maintain a balance between critical frankness and opinion. If artists are often “placed below the bread-line,” while the country’s art institutions appear to flourish, why does she continue to work as an artist? Darragh acknowledges the all-encompassing significance of being a maker of art “and the excitement of discovering new thoughts or [the] materialization of ideas… art can take you out of the world.” And in response to the country’s art institutions: “Artists carry the cultural memory, the institutional memory is impermanent as workers from art institutions come and go…. Art is proof of success.”

And when Darragh draws attention to the “consistently inconsistent” income sources that artists are often required to generate to make a living, (the odd sale, part-time teaching jobs, working in hospitality), Laird extends the conversation: “All workers now feel like artists as much as they don’t know when their next contract will be, or their next pay-cheque.”

Yet, I see Art Everywhere is not just a series of essays. Designed by Fiona Gilmore it will sit loudly and uncomfortably on every living room table in the country. It reads like a feisty introduction to Art and Reality 201, but looks like a work of art. In addition to its limited edition of 300 - and its larger-than-practical-for-putting-in-your-library-at-home scale - nearly 70% of its content is images of Darragh’s work; installations, sculptures, drawings, collage works and photographs from 1998 to 2013. And while it may initially seem rowdy - like being drawn into a chaos of ideas, being formed and reshaped - it is more than the sum of its many parts.

Warren Feeney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.