Terrence Handscomb – 26 May, 2015

Many close to the show saw some of the critical reaction to the retrospective as unfair maverick misinformation. However their heated reaction (albeit well out of the public gaze) to online forums, is not merely a localised anomaly, but it is a symptom of a wider condition: those whom have, until recently, controlled the contemporary art narrative, must now vie for attention with what they see to be as the historically ill-informed, misinformed, disinformed and even the talentless - all of whom have found a public voice, usually through social media.

Billy Apple®: A Life in Parts

Christina Barton

112 pp, illustrated chronology

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2015

Published on the occasion of the retrospective exhibition Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else, curated by Christina Barton, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 14 March - 21 June 2015

History is a strange beast and art history, it seems, is the strangest beast of all. Of the various histories, art history has, in the modern era at least, developed the odd capacity to spawn even stranger progeny: that which is born of art history’s intellectual engagement with contemporaneity. That which is born of art history’s persistent intellectual engagement with the not-yet-historical - i.e. the present - invariably leads to maven historiographies whereby the past is evoked to give meaning to the present. This was most notably the case when, in the late nineteenth century, classical principles (particularly universality), were evoked by the academy to repudiate the ‘inferior’ but invasive principles of modernism. I call this forensic historicity: the occultation of new (and therefore speculative) undocumented speculation, by established historical ‘evidence.’

When forensic historiography is used to empower our understanding of the contemporary as well as the historical, and the ‘illustrated chronology’ Billy Apple®: A Life in Parts is no exception, . However, when tight curatorial principles are based on strong historical fact, as is the strength of the retrospective exhibition Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else, and the illustrated chronology cum catalogue Billy Apple®: A Life in Parts. Beware however, that when a serious curatorial endeavor is forced to occupy the same critical grounds as the internet-based art-critical forums that are being increasingly occupied by flamers, bloggers and maverick intellectuals, all hell can break loose.

Street-level insurgencies into the art-critical community, are not mere isolated instances of lapses of critical discipline, or what Vanity Fair recently called “…the erosion of supervision, accountability and trust in this untamed discofever digital landscape,” (1) to many art-institutional professionals and historians, the condition has become endemic.

Recent critical reaction to Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else has provoked uncommonly seen, behind-the-scenes argy-bargy and hurt feelings, culminating in an egregious call for Creative New Zealand to not support online art-critical forums, like EyeContact, for a perceived undisciplined lack of editorial leadership. The not-so-private commotion following certain critical assessments of Billy Apple’s retrospective was, as I see it, exacerbated by the notable absence of a critical curatorial essay, and/or director’s comments that should have accompanied the retrospective.

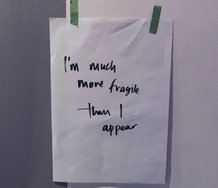

Many close to the show saw some of the critical reaction to the retrospective as unfair maverick misinformation. However their heated reaction (albeit well out of the public gaze) to online forums, is not merely a localised anomaly, but it is a symptom of a wider condition: those whom have, until recently, controlled the contemporary art narrative, must now vie for attention with what they see to be as the historically ill-informed, misinformed, disinformed and even the talentless - all of whom have found a public voice, usually through social media. With various mixtures of in-your-face wit, adversarial vitriol, exaggerations, incoherent and unreadable texts and art-critical speculations punctuated by the occasional politically savvy nonce, a new breed of street-level arts commentary is burgeoning.

If this is the case, then it also begs the question: can the historiographic fidelity of a serious and accomplished chronology of Billy®’s long and storied history, albeit loyally laid out in Billy Apple®: A Life in Parts, fill the critical no man’s land vacated by a strong explicative monograph that in all likelihood should have accompanied the show, despite the strategic choice not to do so?

Recently, a call for submissions was sent out for an academic conference discussing the role that a media-enabled critical culture is increasingly playing in the dissemination and reception of arts commentary. For example, online forums (such as eyecontactsite.com and blouinartinfo.com) and the social media networks (Tumbler, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube …) are increasingly replacing the traditional “… privileged places of art-critical exposure - catalogue essays, curatorial remarks, broadsheet review, glossy art magazine article, academic research paper, art-historical monograph[s].” Increasingly, these traditional outlets “… have been challenged by new means of accessing the art-critical discourse.” (2)

There is a principle widely practised by professional historians: at least fifty years should elapse between the occurrence of (historical) events and their historiographic presentation (art historian Tony Green reckons it’s seventy years). During this time, so the principle maintains, history must be given the opportunity to ‘settle’ and to allay the inclination to tarnish burgeoning historical fact with excited or willful speculation. Of course, this principle does not always suit the contemporary art market and the numerous MOMAs where the idea of ‘contemporaneity’ and ‘the new’ can amount to nothing more than orchestrated optimism and the saccharine taste of novelty. It can take time for great art to become great.

The myth of the new has a way of engendering dysphoria and optimism in equal measure. It plays equally upon our fearfulness, uncertainty and our subjective malleability, as well as engendering a willingness to elevate whole new generations of artists whom, as the master satirist Evelyn Waugh’s delightfully and mockingly observes, are “notable for elegance and variety of contrivance with so much will and so much ability to please.” (3)

Before history settles, there are those of us who will always do our best to make it settle exactly how we would like, and Billy Apple® is no exception. Always the adman, Billy Apple® likes to control the representation of his own brand, which of course, is judiciously indistinguishable from Billy Apple the artist. One of Apple’s important talents is his shrewd ability to choreograph his own self-history - notably the evolution and representation of his identity - and then get others to fold it back into his work in such a way that documents like Billy Apple®: A Life in Parts or Anthony Byrt’s sycophancy (Metro, April 2015, pp. 74-82) become wholly compliant to Apple’s exacting and tenacious artistic will.

The difference between artists’ retrospective and survey exhibitions can be significant, although in practice the terms are often used synonymously. Treating Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else as a retrospective is both deserved and fitting because Apple’s vast oeuvre comes replete with its own history effectively wound into the representational fabric of the brand Billy Apple®. Retrospectives are about authorising histories and recognizing career-long contributions to the arts. Like being inducted into a hall of fame. On the other hand, a survey, the exhibition Yvonne Todd: Creamy Psychology (City Gallery, Wellington, 6 December 2014 - 15 March 2015) has no need to authorise a history in the same way that a retrospective may do, but instead focuses on comparing and contrasting and assembling in one place an extensive body of work, where subjective engagement is cleverly choreographed. Todd’s survey plays not so much on the history of her work, but instead, and with great curatorial savvy, assembles Todd’s considerable corpus, laying each work out against the other in clusters of themes and moods, over two floors, as it weaves a cleaver curatorial narrative. Disappointingly, this curatorial achievement is diminished by an annoying, self-serving, undisciplined (and theoretically dated) title for the show, which is wholly incapable of bearing the allegorical weight of Todd’s extensive oeuvre.

The historical gutsiness of brand Billy Apple®, and the historiography that sustains its artistic integrity, are mainly informed by a vast body of historical documentation, much of which lies in Apple’s personal archive. Apple’s personal archive is a vast repository of historically important artifacts, the availability of which Apple himself carefully monitors self-selectively: images of a socially connected Billy, Billy with David, Billy with Andy, or Barry before Billy, Billy as Billy®, and so on. Thankfully Barton’s text does not play on Apple’s own oral history to the same extent that Byrt’s faithful Metro essay does. Nor does Barton’s text sanitise Apple®’s oeuvre without mentioning the subjectivising historical nuances that complete the brand. There are however, disappointing gaps, made inevitable by Barton’s restriction of certain pieces. Apple’s body works and other mentioned-but-not-explored historical blemishes remain largely airbrushed out of Barton’s historiography, although key ‘scandals’ such as Apple’s Serpentine Gallery fiasco are mentioned, albeit briefly (p. 29). The tenor of Barton’s text makes it clear that she is determined not to play into the hands of ill-informed public whose visual vocabularies are acculturated more by reality television and tabloid scandal than by selective historical facts which sit nicely with the audience-safe programming of Auckland Art Gallery.

Barton is an accomplished historian who clearly possesses what Boston Review journalist Meghan O’Gieblyn recently described as “… a quality shared by the best historians: the ability to make (her) subject integral, a sun around which everything else orbits.” (4) However, A Life in Parts is no mere “narrative constructed around certain dates that serve as pointers to significant events, or as opportunities to reflect on larger ideas and issues that underpin Apple’s practice,” as Barton quietly notes in the preface (p.7). With an aura of calm expertise and editorial dispassion, Barton’s text is a subtle politico-historical statement whose authoritarian conceit remains well concealed.

As a result of the already-mentioned critical responses to Apple’s retrospective, Barton’s long-held intolerance of ‘lazy’ online critics, has become surprisingly visible. Without much embellishment, one may conclude, that the problematic species of self-serving, scandal-hungry and undisciplined online art-political commentator, could quite easily be described, in the words of theorist and journalist Aude Lancelin, as those with a taste for worst-case politics (la politique du pire). That is, those commentators ‘… who would never give up an antagonism that excuses them from having to abandon their intellectual laziness and relinquish even a single one of their prejudices.’ (5) However, at our peril we should never underestimate the efficacy of the soap-box politics in the arts. In an age of twittered-out knee-jerk flaming, an art-critical voice can find less power in the veracity of objective truth (in this case, ‘historical’ truth) than it may find it in the intoxicating power of its utterance. The perlocutionary force of any art-critical declaration lies not in what is said, but that it is said.

When intellectual schadenfreude gets a taste for cruelty it likes to bite, and bite hard; but when criticism takes satirical form and then folds in the sweet taste of irony, it can also provide a welcome tonic against the excruciatingly happy-face place of the chattersphere, where long ago Facebook got rid of its dislike-thumbs-down button, thereby signaling that the giant social network had became a “place where nobody flops.”

A close reading of A Life in Parts (and not necessarily a willful one), reveals that the archive, together with its careful and honest explication colors its intention. After all, this document is a chronology and not a polemic. Yet in a subtle way Barton’s tight historical intention relinquishes any need to add a subjective tenor to its narration, while shrewdly denying anything that does. However, that is all her text seems to be: a repository of historical purities. It is an extensive (but not exhaustive) history of documented fact, with little or no intuitive, nor up-front-and-personal, critical engagement with Apple - or to summon the spirit of Blanchot and evoke the language of Badiou: as a historical document, A Life in Parts does not come face-to-face with the subjectivisable body of Billy Apple® and the artistic will that vivifies it (6).

Barton seems content to leave interpretive narratological assessments of Apple’s history to others. A Life in Parts is not “… an exhaustive chronology, but a narrative constructed around certain dates … [and] significant events.” The document, as Barton argues, is a chronological template or “a preliminary point of entry, using the exhibition history and reading list…” as a resource “…to extend [our] understanding.” Because Barton’s narratological structure is forensic and neither interpretive nor subjective, any understanding we glean from the text will, in all likelihood, be historical. Apple’s history, which is inexorably enforced by the tenacity of its brand, is already a state of representation which cannot be separated from its concept nor its object. Despite there being a gallery full of things, we should never underestimate the transcendental efficacy, nor the representational thrust, of the brand Billy Apple® and the post-object considerations that supports its history.

Historical rigor, and the value that archival substance plays in its articulation, is the seminal condition of Barton’s historiography. The importance Barton’s narrative places on the forensic document-as-evidence over, for example, an intuitive engagement with the actual art object, can be traced back to her 1987 art history master’s degree thesis Post-object Art in New Zealand 1969-1979, (7) wherein the importance of documentation plays a significant role. Although the phrase ‘post-object art’ appeared earlier, Barton attributes its first antipodean use by NZ and Australian artists whom, as early as the late nineteen sixties (in particular Australian born artist Terry Smith (b. 1944)), were declaring “…the redundancy of the object, (and) instead placing the type of context-based post-minimalist sculpture which involved the spectator in a new and active way” (p. 7). With the eliding of the object in their practices, many post-object artists ‘…realised the need for effective documentation, not simply as an adjunct to the work but as an integral part of the work…’ (my emphasis). Importantly, documentation is ‘…evidence of work done, (and) it often served as the only tangible residue of a particular piece’ (p.44), a condition that continues to suffuse Apple’s work.

It is a matter of speculation to what extent Barton’s early engagement with post object art, has conditioned (if at all) her distrust of the type of undisciplined and historically unsubstantiated speculations, which will inevitably plague the discourses that engage contemporary art. As a retrospective exhibition, The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else is a place where history reassess that which was once radically new and tests the veridicality of that moment against time itself. Clearly, Barton’s careful curatorial efforts are a significant achievement and deserving of one of New Zealand’s great artists, but A Life in Parts does no more than its mandate requires: it dispassionately lays down a history of Apple’s vast oeuvre.

Twentieth century physics and non-classical logics tell us that there is no absolute now because the intuition of time-as-linear-flow is not only relative, it is also chronically mutable. If so, any idea we have of a truth entailed by the radical new, will always include a retroactive component spoken in some future anterior tense - i.e. “sometime in the future it will have been the case.” In other words, until history settles, the at-first-unrecognizable truth of radical newness is up for grabs. More so, it seems, in the hyper-subjective no man’s land of the internet’s chattersphere.

Terrence Handscomb

(1) James Wilcott, “The Sweet Smell of Disgrace,” Vanity Fair, 657, May 2015, p. 84.

(2) Art Criticism 2.0, conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 6 November, 2015. Deadline for abstracts (200 words) 14 June 2015. Downloaded 17 May 2015.

(3) Evelyn Waugh, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, London: Chapman and Hall, 1957.

(4) Meghan O’Gieblyn’s book review of ‘American Apocalypse: A history of Modern Evangelicalism’ by Mathew Avery Smith, Boston Review, March/April 2015.

(5) Aude Lancelin, Confrontation: Alain Badiou, Alain Finkielkraut. A Conversation with Aude Lancelin, trans. Susan Spitzer, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014. p.ix. Note also the French phrase la politique du pire (worst-case politics), refers ‘…to a deliberate strategy of allowing a situation to deteriorate to the point where some drastic action, whether revolutionary or counter-revolutionary, is required to change it’ (ibid.).

(6) Maurice Blanchot (1907 - 2003) was a French, writer, philosopher and literary theorist whose principle ideas (drawn from the writings of Martin Heidegger, Georges Bataille and Emmanuel Lévinas) on radical alterity and our face-to-face ‘relationship to the unknown,’ informs this point.

(7) Christina Barton, Post-object Art in New Zealand 1969-1979, Thesis, MA - Art History, University of Auckland, 1987. Fine Arts Library 707.51 B293.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.