Will Gresson – 25 May, 2015

The depth of research which Martin Parr, Thijs groot Wassink and Ruben Lundgren have undertaken - and the resulting scope of the photobooks on display here - opens a multitude of windows into a region still not particularly well understood by Western audiences. There is a level of access here which does much to vindicate the curators' interest in the photobook as a kind of mediated medium that provokes further consideration of what this sort of publication might reveal about other territories.

London

Books of historic photographs

The Chinese Photobook

Curated by Martin Parr and Wassinklundgren

17 April - 5 July 2015

“The image is never innocent.” Over the course of the next hour, this is the sentiment which repeatedly comes to the fore as I discuss the exhibition ‘The Chinese Photobook‘ with Thijs groot Wassink, one half of artist collective WassinkLundgren . This duo of Dutch photographers, together with British photographer Martin Parr, has spent the better part of the last eight years researching the largely unexplored field of Chinese photobook publishing. Born out of Parr’s interest in propaganda as well as the dynamics of photobooks, the collaboration has proven incredibly fruitful - as evidenced by the touring exhibition currently showing at London’s Photographers’ Gallery and its accompanying publication.

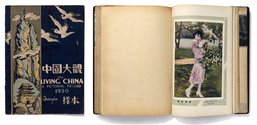

Beginning in the Imperial China of 1900, the show presents photobooks spanning over one hundred years of Chinese history, divided into six roughly chronological chapters that trace the dramatic social and political changes in China up until the present day. This large time scale incorporates multiple foreign perspectives, from the colonial powers of the early 20th Century to Japanese propaganda in the 1930s and 40s, as well as contemporary journalists and fine art photographers in the build up to events such as the Beijing Olympics in 2008. Within this broad spectrum the curators are able to highlight the incredible changes wrought throughout these different periods of history, all illustrated through different photobooks published along the way.

The exhibition opens with the largely foreign perspective of China in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, as the Nationalist movement was beginning to gather momentum. Particular highlights from this section include a series of aerial photographs, quite possibly the earliest images of China captured from a bird’s eye view, taken by French military forces. Wassink is philosophical about the Western influence on these early images, either due to the foreign armies or photographers responsible for them, or the largely western audience they were addressing. This in turn influenced Chinese photographers to shoot with a similar emphasis.

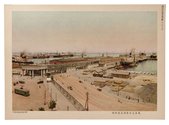

The conflict between China and Japan over Manchuria, which began in the early 1930s and continued on until the conclusion of World War Two and the Japanese surrender, is also addressed here in a separate section. Two publications with almost identical layouts sit next to each other, one showing Japanese propaganda aimed at legitimising their invasion and occupation, the other showing gruesome scenes of wounded Chinese at the hands of the Japanese army. So similar is the design that for a moment, the difference in message is momentarily blurred, before coming vividly and profoundly into focus.

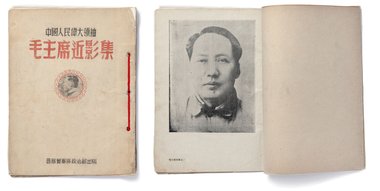

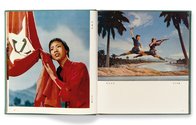

The two large central sections of the exhibition trace China’s transition to communism from the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, through the Cultural Revolution and the creation of Mao’s expansive cult of personality, and on into new spaces opened up after his death in 1976. The cessation of private publishing during this time, and the growth of the state publishing apparatus, is a fascinating insight into the development of the regime’s authority. Comparing the small and rather humble pocket sized publication ‘Grand Military Parade at the Inauguration of the Central People’s Republic of China’ from 1949 with the huge ornate book ‘China’ published ten years later for the anniversary of the country’s founding, shows the pace of development and the level of consolidation that the government had undertaken in just a decade.

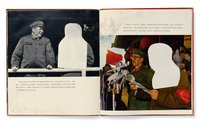

One of the most intriguing dynamics that comes through in the later stages of the exhibition is the degree to which the propaganda machine of the party occasionally seemed to throw not only individual citizens into difficulties but also the regime itself. This is perhaps best illustrated in the case of Lin Biao, a senior figure in the Chinese Army, highly regarded and praised by Mao, who later fell afoul of the regime and died under mysterious circumstances with his family in a plane crash in 1971. Branded a major counter-revolutionary force, many tried to erase him from the official history of the party. While the government of course could do this with images released subsequent to his death, images that had already been published during the years when he was still in favour couldn’t be so easily altered.

Consequently within the exhibition, several copies of the same image are shown, where the owner has gone and altered the image of Biao themselves, either crossing the face out, covering the whole figure with white, or trying to cover over the image in black pen (leaving a ghostly apparition standing smiling at Mao, in one example). Wassink points out that while altering Biao’s image was a sort of insurance against being accused of sympathising, people had to be careful not to alter the image of Mao by trying to cut pages out or glue them together, for example. A seemingly pedantic exercise in censorship, the results could be grim for those caught vandalising the wrong image, or even vandalising the right image the wrong way.

Fast forward then to post-Tianaman Square China and something interesting becomes apparent. In the aftermath of the student protests in 1989, the now famous images of the ‘tank man,’ the famously defiant protester who stood in front of the tank as it broke up the protests is perhaps predictably banned. To this day, the image still can’t be shown in China, and the iteration of the exhibition which travelled to the country and the accompanying publication both have been censored accordingly.

Around the same time, a publication from the government which sought to brand the demonstrators as violent antagonists was published, entitled ‘The Truth about the Beijing Turmoil.’ Carefully selected images of people fighting were labelled with highly dubious captions about “rioters” bludgeoning injured soldiers. While this sits alongside the images in the London show, this photobook now too is banned in China, perhaps in acknowledgement of the fact that for many in the West the regime’s crack-down on the protestors was a human rights violation (the full extent to which is still unclear). What we see then is that the government too occasionally becomes tangled in its own web of propaganda, and must sometimes walk a tightrope between maintaining the authority of the regime, while still leaving enough space to build links with the West.

It’s nuances like this, of which there are many, that make this collection of images so fascinating. The depth of research which Martin Parr, Thijs groot Wassink and Ruben Lundgren have undertaken - and the resulting scope of the photobooks on display here - opens a multitude of windows into a region still not particularly well understood by Western audiences. There is a level of access here which does much to vindicate the curators’ interest in the photobook as a kind of mediated medium that provokes further consideration of what this kind of publication might reveal about other territories. These publications are a visual map not just in terms of the images they present but the context that they frame them in, and as you leave the exhibition, it’s interesting to consider what another ten years might look like.

Will Gresson

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.