Scott Hamilton – 4 May, 2015

The video showed Faletau and two of his brothers making the shape of Tonga's most famous monument. The three actors were naked except for black tupenu, and remained silent throughout their performance. Two of them were kneeling, with their hands on the ground, so that they resembled the pillars of the Ha'amonga ‘a Maui; a third lay across their bent backs on what looked like a thin mat, so that he resembled the trilithon's lintelpiece.

Near the northwestern corner of Tongatapu, the capital island of the Kingdom of Tonga, a crumbling road passes a few acres of open ground surrounded by bush and plantations.

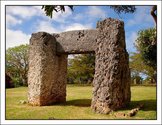

On most weekdays, several stalls stand on the edge of the clearing: dust from the road flecks their coconut bracelets, their paua shell earings, and their pandanus leaf fans. Beyond the stalls the trilithon Tongans call Ha’amonga ‘a Maui - the Burden of Maui - can be seen. Two rectangular slabs of coral stand upright; a third rests on top of them, making an archway about twelve feet high. A trail runs from this archway into a strip of bush where the sound of the sea mixes with the hissing of insects and the rattling of lizard tails. The trail passes smaller, overgrown monuments, before reaching a narrow beach and a reef of coral that was quarried hundreds of years ago.

Every tour guide on Tongatapu brings his customers to Ha’amonga ‘a Maui, and every tourist, no matter new to the kingdom or uninterested in history, recognises the monument. The Ha’amonga adorns T shirts and tea towels sold at Tongatapu’s airport, is pasted onto bottles of local beer, and decorates the crests of sports teams and civic associations. The entrance of the Billfish Bar, a popular hangout in Nuku’alofa, Tonga’s only city, features a miniature version of the trilithon made with slabs of concrete rather than coral.

Carbon dating and local stories suggest the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui was raised in the thirteenth century, when the country had been united by the Tu’i Tonga monarchy, and had begun raiding and trading with distant archipelagos like Fiji and Samoa. The trilithon became the focus of Heketa, capital village of the fledgling Tongan Empire. A century or so later Tonga’s capital was moved a few kilometres southwest to Mu’a, a village protected from heavy seas by a lagoon.

As their influence spread further through the Pacific, the Tongans created new monuments. At Mu’a they laid slabs coral on top of one another to create pyramids over the graves of kings and queens; in colonies like Samoa and ‘Uvea they raised stone forts. But where the function of these structures is easy to discern, the purpose of the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui is obscure. Its shape is unparalleled in Tonga, and indeed in the Pacific, and neither oral traditions nor contemporary scholars can agree about its meaning.

Some stories suggest that the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui was raised on a distant island, then made into a yoke that the demigod Maui dragged to Tongatapu; others insist that it was built by Momo, the tenth Tu’i Tonga, who wanted its three parts to celebrate his three sons; others say that the monument was made to decorate the tomb of Momo; still others insist that Tu’itatui, the eleventh Tu’i Tonga, built the trilithon and made it the entranceway to his quarters at Heketa.

King Tupou IV, who ruled Tonga from 1965 until 2006, decided that the trilithon had been a sort of observatory where his ancestors had calculated the dates of equinoxes and solstices. Tupou IV had his interpretation printed on a billboard that he raised close to the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui, but few scholars have taken his foray into astroarchaeology seriously. At the 2011 conference of the Tongan Historian Association a researcher named Daniel Fale presented a paper intended to support Tupou IV’s contentions. Firita Velt, Tonga’s only resident astronomer, was in the audience, and was unimpressed with Fale’s claims. The two men argued angrily, and the meaning of the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui remained unresolved.

Perhaps because of its mysterious history, the Ha’amonga a Maui has often attracted the attention of cranks and fantasists. In his book The Lost Civilisation of Lemuria, Frank Joseph claims that it was built by migrants from a teeming and technologically sophisticated Pacific continent that suffered the same misfortune as Atlantis. Martin Doutre, a former Mormon missionary whose books insist that Europeans rather than Polynesians are the indigenous peoples of Aotearoa and the rest of the South Pacific, believes that Tonga’s trilithon was made by ancient Celts. A palangi hotelier who takes his guests on tours of Tongatapu, he tells them that the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui was the work of Chinese masons, and cites Gavin Menzies’ absurd but bestselling book 1421: the Year China Discovered the World in defence of his view.

Ha’amonga is the name that Sione Faletau gave to a video that has just played for six weeks inside the OTARAcube, a converted shipping crate funded by the Otara-Papatoetoe Local Board, managed by the Manukau Institute of Technology, and located close to Otara’s bus station and its branch of McDonalds.

The video showed Faletau and two of his brothers making the shape of Tonga’s most famous monument. The three actors were naked except for black tupenu, and remained silent throughout their performance. Two of them were kneeling, with their hands on the ground, so that they resembled the pillars of the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui; a third lay across their bent backs on what looked like a thin mat, so that he resembled the trilithon‘s lintelpiece. The brothers were brightly lit, but the space around them was as ominously black as the backdrop to one of Caravaggio’s scenes. A fast, rasping drumbeat borrowed from a Tongan dance song seemed to mock their stillness.

In a second scene shown near the lower right-hand corner of the video screen, a pyramid-shaped pile of ngatu seemed to quiver; it might have hidden a human being. Eventually one and then another of the pillars of the ha’amonga moved slightly under the weight of the lintelpiece, and the whole monument trembled, so that one feared it might fall. The brother who was playing the lintelpiece lay with his eyes closed, and gave no sign that he knew what a burden he was to his siblings.

Faletau’s video lasted six and a half minutes, which means that it screened about two hundred and thirty times every day.

Ha’amonga reminded me initially of the work of Kalisolaite ‘Uhila, the Tongan-New Zealand performance artist who almost won last year’s Walters Prize. ‘Uhila’s performances have the same formal simplicity as Faletau’s video, and one of them, 2013’s Fa’e Huki (Mother Brother), saw the artist falling to his knees and letting his niece and other members of his family sit on his bent back.

But where ‘Uhila’s performances are often lengthy, gentle improvisations The Ha’amonga was short, careful and controlled, and induced, in me at least, a sense of uneasy anticipation. As Faletau’s unseen drummers worked mercilessly away I waited for his trilithon to tumble, and for some strange and perhaps sinister being to burst from the ngatu chrysalis in the corner of the screen.

By substituting human flesh for stone, Faletau reminded me of the meaning of the word ha’amonga. Like many of the ancient monuments we photograph and sentimentalise, from Stonehenge to the Acropolis to the temples of Angkor Wat, the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui is a product of oppression.

By the time the trilithon was built the egalitarian, marine-based society of the Lapita people, who settled Tongatapu three and a half thousand years ago, had evolved into a centralised, hierarchical civilisation sustained by plantation agriculture and war.

As their wealth and territories grew, Tonga’s rulers began to mystify themselves, claiming descent from the god Tangaloa, and commissioning poets and dancers to perform in their honour at Heketa and Mu’a. The ruling class lived by taking tribute from its overseas colonies and from the tu’a, or common people, of Tonga. Tonga’s priests taught that class divisions persisted even after death: the souls of the kings and queens and chiefs buried at Mu’a journeyed across the sea to the easeful western island of Pulotu, but dead tu’a reincarnated as mosquitoes or small animals.

Labour as well as crops was taxed by Tonga’s rulers, and it is likely that the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui and the monuments of Mu’a were raised by tu’a conscripted for the task. Its pillars and lintelpiece had to be quarried, shaped, transported, and assembled without modern tools or vehicles, and must have cost tens of thousands of hours of toil.

Because it seemed to point towards the human effort that went into the making of Tonga’s trilithon, Faletau’s video reminded me of Bertolt Brecht’s poem ‘Questions from a Worker Who Reads’. When confronted by conventional accounts of ancient history, with their lists of monuments and monarchs, Brecht’s worker responded with a mixture of awe and exasperation:

Who built Thebes of the 7 gates?

In the books you will read the names of the kings.

Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

And Babylon, many times demolished,

Who raised it up so many times?

In what houses of gold glittering Lima did its builders live?

Where, the evening that the Great Wall of China was finished, did the masons go?

Great Rome is full of triumphal arches.

Who erected them?

Even after it was constructed, the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui may have remained a symbol of oppression for medieval Tongans. In their 2013 paper ‘Stone Architecture, Monumentality, and the Rise of the Early Tongan Chiefdom’, archaeologists Geoffrey Clark and Christian Reepmeyer argued that the trilithon was the focus of the ‘inasi ceremony, which saw Tongan farmers presenting the best parts of their harvests to their king. Anthropologist ‘Opeti Taliai believes that the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui was designed as a symbolic gateway through which Tonga’s commoners had to pass as they brought offerings to the king at events like the ‘inasi. By stepping through the archway, the tu’a affirmed their servitude.

But Sione Faletau’s work suggested that the Ha’amonga ‘a Maui was a symbol of unity, as well as inequality. By choosing three brothers to comprise the three parts of his monument Faletau reminded his audience of the intricate genealogical ties that connect between Tongans of different classes.

It is not unusual for a Tongan noble with a state salary, an estate, and a seat in parliament to have cousins who grow talo and sleep under leaky tin rooves. Wealthy and impoverished family members drink kava together, and fulfil complex obligations to one another.

Blood ties complicate class differences, and soften the inequality of Tongan society. In an essay published at the end of the 1960s, Elizabeth Bott, an anthropologist, psychoanalyst, and confidant of the Tongan royal family, praised the ‘differentiated but interdependent’ quality of Tongan society, and argued that this quality was embodied in the kava ceremony, where drinkers are seated and served according to their social status. The kava ceremony brought Tongans together, Bott said, but it also reminded them of their differences.

The great Epeli Hau’ofa made the same point a decade later in his poem ‘Blood in the Kava Bowl’, which celebrates the genealogical ties that bring powerful and powerless Tongans together around kava bowls. Hau’ofa’s poem mocks a left-wing palangi scholar who ‘talks of oppression’ in Tonga but ignores the power of blood:

Across the bowl we nod our understanding of the line

that is also our cord brought by Tangaloa from above

and the professor does not know.

He sees the line but not the cord

for he tastes not the blood in the kava.

A lot has changed in Tonga since Bott wrote her essay and Hau’ofa wrote his poem. The country’s monarchy has lost many of its powers, rioters have burned and looted the property of their powerful relations, and a commoner once imprisoned for treason has become Prime Minister. Like Sione Faletau’s monument, Tongan society is shaking. Can it hold together, or will old burdens bring it down?

Scott Hamilton

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

I'm reminded of Italo Calvino’s novel ‘Mr Palomar’, the chapter “Serpents and Skulls”, in which the protagonist is being guided ...

Richard Taylor

But thanks for that link to Dali. Some fascinating art there by him I had never seen.

Richard Taylor

But what I like about Scott's writing is that, while he understands art history and theory, he doesn't go in ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 5 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 8:54 a.m. 4 May, 2015 #

This work also has a witty connection with Dali's famous photograph “In Voluptas Mors". See https://rebeccambender.wordpress.com/2014/05/06/body-skulls-salvador-dali/

Richard Taylor, 9:29 p.m. 12 May, 2015 #

But what I like about Scott's writing is that, while he understands art history and theory, he doesn't go in for the fashionable theory of vague things such as 'the corporeality of the body. He goes to Otara, looks at what he sees, and describes it more or less as he sees it.

I don't see any connection with Dali. Great artist as he was. Dali was a fascist sympathiser for a start (which may not matter per se, I like his art a lot and say, the writing of Celine, Pound, Eliot are all fascinating and great, but of a different...whatever the word is) which puts him in a different category?

This is conceptual art (it seems to me) referring to Tongan history and by extension of course world history and the nature of art.

Billy Apple, as perhaps a counter-example, seems to be only about art, and himself. Unless there is a tribe of one who freeze their own blood for 'immortality' or unless we can get some money from all that gold and pre-paid bills he got paid, and all the millions he boasts he will be making with his art. The artist needs to live like anyone else? Well, they get paid enough. I doubt that these Tongan artists get the cash Dali got or Apple and his mates will get.

The test of art will come when they limit their income to an average income. And work for their art and not for money only.

Richard Taylor, 9:14 p.m. 12 May, 2015 #

Good review Scott. Interesting art work. What does ngatu refer to?

The monument could well be a symbol of hierarchy but it is not easy to know.

Richard Taylor, 9:31 p.m. 12 May, 2015 #

But thanks for that link to Dali. Some fascinating art there by him I had never seen.

Ralph Paine, 10:33 a.m. 13 May, 2015 #

I'm reminded of Italo Calvino’s novel ‘Mr Palomar’, the chapter “Serpents and Skulls”, in which the protagonist is being guided by a Mexican friend round a pre-Columbian archaeological site. While Mr Palomar’s friend spins elaborate and colourful stories of the god Quetzalcoatl, nearby a group of local schoolchildren is being told by their teacher that although the ancient stone structures and carvings at the site can be accurately described and dated, no one actually knows what they mean.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.