John Hurrell – 14 November, 2017

Magritte and de Chirico are conspicuous references here: painters, not collagists or photographers. The irony is that—despite his origins—the physicality and materiality of Stezaker's manipulated and realigned found photographs is really important. The works are not at all abstract, dry or coldly cerebral like those of his earlier Conceptualist colleagues, but highly emotional, and subtle. They can be very disturbing and visceral, but also very, very funny.

Wellington

John Stezaker

Lost World

Curated by Robert Leonard

26 August -19 November 2017

A touring show that starts in Wellington, and goes on to New Plymouth, Christchurch and Melbourne, this presentation of John Stezaker collages, film and found sculptures (47 works picked out of 11 ongoing series) is an exciting chance to look closely at the psychological effects of his juxtapositions and compositional nuances, via cut and pasted film stills. He last had work in Wellington as part of Pictura Britannica in 1998, that legendary show where Paul Holmes raised a huge kerfuffle over Tania Kovats (for six months art was front-page news), and where there were superb contributions not only from Stezaker and Kovats, but others like Ceal Floyer, Georgina Starr, Gary Perkins and Bethan Huws.

Initially Stezaker was known as an early British conceptualist (1), a contemporary of language-based artists like Victor Burgin, Art & Language, John Hilliard and Stephen Willats, but his career changed direction in 1981 after he saw a Joseph Cornell exhibition at the Whitechapel gallery. Although he has never really moved away from a preoccupation with how art functions with its audience, he did become more intrigued by the possibilities of collage and its ties with Surrealism.

Magritte and de Chirico are conspicuous references here: painters, not collagists or photographers (2). The irony is that—despite his origins—the physicality and materiality of Stezaker’s manipulated and realigned found photographs is really important. The works are not at all abstract, dry or coldly cerebral like those of his earlier Conceptualist colleagues (he now is considered a traitor by some—by virtue of his moving away from text), but highly emotional, and subtle. They can be very disturbing and visceral—absolutely intestinal—but also very very funny. They need to be seen directly in a gallery, not in books or online where a lot is lost in detail and scale.

Upstairs in City Gallery, there are four rooms allocated to Stezaker’s projects. One is a dark space for a looped projected film made of hundreds of photographed crowd scenes and some objects, one frame only for each found image. The flurry of flickering and seething images means you are never quite sure what it was that swirled past on the screen. How much did you imagine (or guess) and how much was planned by the artist? The unconscious mind holds a fascination in moving image and static, in both cases reaching into involuntary bodily and convulsive zones.

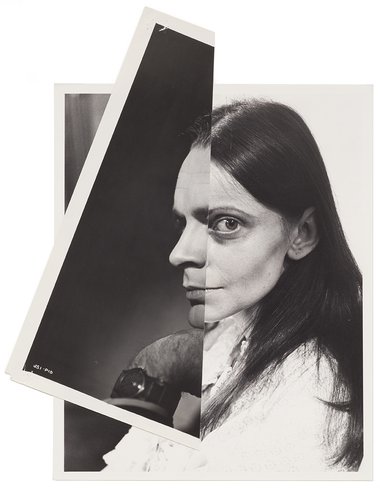

In the three large white-walled spaces, the collages—made from 40s film stills featuring unknown actors, and old postcards—dominate. When (for example) combining male and female faces, or pairs of each, Stezaker craftily aligns eyes and mouths or the sides of noses so that physiognomies partially blend or match up, but the rest of the images stay out of sync along the straight diagonal border—maintaining a tension that disavows perfection or closure. Or, as with the picturesque postcards of caves, cliff-faces or aqueducts laid over profiles of conversing couples, the overhanging trees or steep rock faces become the silhouettes of noses or locks of hair, creating a blurry gestalt that partially resolves and (importantly) partially fragments further. Incongruous 2D and 3D spaces attempt to merge.

Although Stezaker‘s work is about Surrealism and hidden psychic energies, there is a sense that it is not that. (Stezaker is too logical.) Nor is it Conceptualist. This is because, like say, sculptor Bill Woodrow, he believes in transparency of process. As with Woodrow’s use of whiteware, nothing is tidied up or removed beyond minimal functionality where one or two elements are matched. Untidy or disruptive scraps become an essential part of the work by embracing the overall randomness, and so he avoids any mystery in technique.

Like Francis Bacon with his smeared portrait paintings, Stezaker is skilled at making collages that really get under your skin. Through brilliant juxtapositions and sudden changes in scale or shifts in position, they disturb in a truly profound way, with a sense of horror and mutilation (like the photographs of WW1 battle-wounded that Breton and his friends were fascinated by) and foreboding. Yet they seem so simple in their economy; so casually constructed; almost accidental even.

Stezaker is consistently obsessive about the tactility of sight, and the way we look at objects or each other or ourselves in reflection—often to find sense in chaos. Individuals gaze fixatedly at white screens or pale circles, alluding perhaps to Horishi Sugimoto and John Baldessari, and referring to their own mechanisms of projection, and the construction of imposed meaning.

Lost World is beautifully hung with restraint and clever juxtapositions, but the first room by the stairs is especially rich in witty resonances, particularly in the way the collages and the sculptures on plinths interact. Five mannequin hands that look as if they’ve had psoriasis and been severed, dominate the centre of the space. In the middle of the main wall is an image where all the protagonists have had their heads removed by removing a strip at the top (symbolising perhaps a rejection of reason by Stezaker) and one of them is about to be guillotined.

Most of the two dimensional works are called Touch, and a few are trimmed found photographs only—ie. made headless—where hands are conspicuous, touching furniture or clothing. Stezaker’s black humour is to the fore because the guillotine work is called Camera, referencing the exposure shutter in the device controlling the descending blade as it cuts through the neck, and acknowledging Roland Barthes’ theory of the photograph and its connection with death, that what we see in the image once existed in a transient form but is not here now.

Three of the images in this room I find particularly extraordinary. Touch, 2014, shows a male figure standing close to a wall and casting a faint shadow on it. The details of the man’s body have been obliterated by his silhouette being filled in with dark grey. He becomes a second shadow, one that replaces the original clothed body.

On another wall are two Double Shadow works, presenting conversing couples at parties that (in profile) have had their bodies removed to leave empty silhouettes. The replacement backgrounds are both inverted, a strategy that really galvanises the composition. One shows a man reclining on a duvet with his feet in the air, and is dominated by rhythmical bands that with his white shirt, unite the whole composition. The other shows distant figures standing outside a large building, the blending combining two very different sorts of deep space.

Stezaker is the sort of genius that arrives intuitively at image combinations that can draw on primal terror as much as give you a fit of the giggles. He is superb at manipulating your emotions (you may dry-retch or shake), often causing contradictory responses simultaneously. Profoundly physical as well as steeped in paradox, they are intimate and modest in scale, never overworked, and always—always—memorable.

John Hurrell

(1) Last year’s catalogue for the Tate Britain show, Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, edited by Andrew Wilson, sheds some light on Stezaker’s early work where he only supported Conceptual Art because it was vehemently anti-Modernist, but disagreed with say, Art & Language, because he saw that group as an extension of Minimalism’s art-for-art’s sake—whereas he wanted more engagement with the world beyond focussing on its mere representation. (See pages 41-42, 91, 93: text and footnotes.)

(2) Stezaker was a painter when he was a young student but all his paintings got destroyed in an artschool fire. He then switched to collage and found photographs. (See Dawn Ades, ‘John Stezaker, Monteur’, in John Stezaker, Ridinghouse Whitechapel, 2011, second edition, p.23.)

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

In vivid contrast to Francis Upritchard, here's an artist dealing with faciality and the abstract machinism of the Face: "...between ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 8:54 a.m. 14 November, 2017 #

In vivid contrast to Francis Upritchard, here's an artist dealing with faciality and the abstract machinism of the Face:

"...between black holes of subjectification and a white wall of signification, faces take shape; these sometimes appearing on the wall, sometimes in the holes. Sometimes the wall is black and the holes white; and so on: the abstract machine is a combinatory, one designed to organise and distribute faciality traits."

And there's even landscapes and faces!

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.