Mary-Jane Duffy – 10 April, 2018

And of course these works are meant to be provocative. In their messed up historicism, they flip the power relationships of our contemporary world. And like the men upset by the perceived attack of the #metoo business on their sovereignty, there are people who want to deny Māori agency and power.

Wellington

Suzanne Tamaki

Native Eye

Curated by Reuben Friend

2 February - late May 2018

I first met Suzanne Tamaki in the nineties at a conference in Paekakariki. She ran a workshop on making costumes and jewellery out of beach detritus and driftwood, and then later MC-ed the catwalk show of all the work. She joked and bantered and turned some sketchy material into hilarious entertainment.

Fast-forward twenty years and Suzanne has turned these interests into a lively practice made up of jewellery, costuming, up-cycled and eco fashion, photographic collaborations, performance, and exhibition curation—tied together with humour and an interest in the legacy of colonialism in Aotearoa.

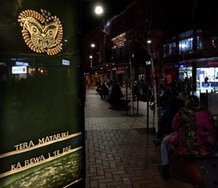

Her latest project is Native Eye in Wellington’s Courtenay Place light boxes. These eight double-sided three metre high freestanding LED-lit light boxes are a micro art environment on the western end of Courtenay Place. They border the street like advertising hoardings. From a car, they’re a set of images flashing by, and on the footpath you can walk around them. They’re a smart piece of urban design, part of a revamp of the area completed in 2008, but also the site of the former Te Aro pā.

It’s this latter point that’s important for Native Eye. Curator Reuben Friend has selected a series of portraits for the light boxes from Suzanne’s ongoing collaborations with photographers Norm Heke, Sarah Hunter and Greg Semu. These portraits repopulate the site with the people of the land—’the tupuna of Courtenay Place’ as Suzanne refers to them.

The series starts and ends with a larger-than-life image of the same young girl dressed in a piupiu with a taniko headband. At one end of the installation in Dream Girls dancers wanted, she holds out a poi, and at the other end in Ahurei, she looks at you warily. She’s not the only child. To have and to hold is a Madonna and child of Suzanne and her son Rameka, and in Songs from the outside a grown-up Rameka plays a guitar. The children look vulnerable and tired.

Some of the portraits are based on historical photos and others appropriate the costumes and poses of history painting. But the real story is in the detail and the symbols—a woman wearing a flag brandishes scissors; a queen in a tiara of bones; the kuia’s tui beer bottle lid necklace; the taniko pattern in buttons; lycra strips woven into a piupiu matched with a knitted korowai; a Wayne Youle fibreglass tiki; the maids proffering cake. Domestic craft materials are repurposed to create a fresh story about adaptation and renewal, while symbols like the cake and the scissors speak for themselves. And there are real taonga too—blankets from Ngaruawahia, kete and hei tiki worn by Suzanne’s cousin in Divided against itself and Everyman needs a pet which are his family’s heirlooms.

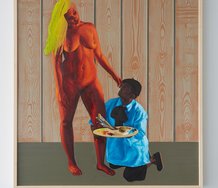

Three of the works are reminiscent of Tracy Moffatt’s colonial series Laudanum except with a humorous twist—sexy housemaids with a slave in A House, and Everyman needs a pet has his hand on the head of a leather-masked man. Like Moffatt, Suzanne is playing with the images of colonialism upturning the power relationships and the symbols of royalty and empire. Her images riff off notions of stateliness and class while showing Maori in all the roles they have played and still play—leaders, workers, slaves, and queens. Suzanne wanted to represent all the roles—the paid and the unpaid; the willing and the coerced.

This has caused a couple of complaints to the Wellington City Council. In Cannot stand a man holding a gun stands behind another man, his slave. The man with the gun is clearly Maori and the slave has whitened skin but he’s Māori too. The image isn’t particularly menacing, more proprietorial and transgressive. One of the complainants to the Council went to the trouble of sending a photo-shopped image swapping the figures around—a white person with a gun lording it over an unarmed Māori man. Well, what’s news there? Being privy to these complaints was a disturbing experience. One of them was so insulting I was seared by its ugliness and racism.

And of course these works are meant to be provocative. In their messed up historicism, they flip the power relationships of our contemporary world. And like the men upset by the perceived attack of the #metoo business on their sovereignty, there are people who want to deny Māori agency and power.

And one last thing: some of the images have been augmented for this exhibition. You have to download an app called Suzanne Tamaki and then use it to look at the work. This works best at night and adds a sweet layer of surprise.

Mary-Jane Duffy

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.