John Hurrell – 12 June, 2018

Stichbury's paintings are terrifically mesmerising, and maybe that is all you require—if you know how to look. In this age of textual overload, where the artworld in particular grinds out excessive amounts of (usually dull) promotional writing, words have to be extremely special to survive. These stories could almost be plots for comic strips planned for the future, or story-boards for films—but which will never be made.

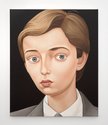

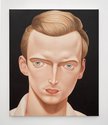

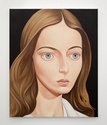

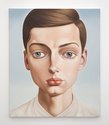

Peter Stichbury’s last portrait exhibition at Michael Lett’s was of wonderfully delicate graphite drawings, but in this presentation he is back to his characteristically glowing, clean-faced, intensely psychological, painted heads. With a graphic flatness that links them to comic strip art, but with extraordinarily fine detail (such as precision eyelashes), he presents four male portraits and three of women. They are usually young—in their twenties, or teenage years—are Caucasian, well groomed, and often exude an idealistic fervour, as if driven by ideologies unknown.

Stichbury generates these images by looking at individual visages on the web, creating identities for the faces, and then doing developmental drawings where he improvises or tweaks the details. For each one he makes up biographies and character types which he converts into texts. These he now publishes with the galley’s list of works. Devised ‘lives’ that supplement or pair with the visual images.

Stichbury‘s paintings are terrifically mesmerising, and maybe that is all you require—if you know how to look. In this age of textual overload, where the artworld in particular grinds out excessive amounts of (usually dull) promotional writing, words have to be extremely special to survive. These stories could almost be plots for comic strips planned for the future, or story-boards for films—but which will never be made.

With big eyes, wide foreheads and bony, sculptural physiognomies—these recent paintings hold your interest for a long time. To make them, Stichbury seems to have been picking online images with a harsh light that accentuates bumps and swellings on bulbous foreheads, pouting lips, and bony nose-bridges. The heads have a greater tactility and mass than before, a more pronounced, more piercing sense of objectness, of presence, of palpable sculptural form.

The show’s title, Altered States, refers to Near Death Experiences (NDEs), a consciousness changing theme that is prevalent throughout the seven texts. In the introduction, several different causes are suggested, one being the chemical dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a naturally occurring (smokeable) neurotransmitter that creates the experience of another dimension. In the stories, the seven ‘Outer Body’ scenarios include: the smoking of DMT; a seven day coma from meningoencephalitis; an operation on a brain aneurism; two psychic experiments—one about an archaeological site on an ocean floor, the other about a secret quark detector made during the Cold War; a drowning where a woman leaves her body, and then returns to come back to life; and finally, metempsychosis—remembered observations from past lives.

You could read these stories one at a time while standing in front of the pertinent portraits, or devour them at home while studying the painted physiognomies online. Some people I suspect will read the texts all in one go—away from the gallery—and then flick through the other pages of the handout to peruse vertically the tiny printed images.

While the stories make gripping reading, they are really footnotes to the portraits, and not essential for understanding them. You could enjoy speculating about NDEs and not even look at Stichbury‘s portraiture achievements, just as the reverse possibility is plainly evident too.

The question is whether the narratives are sufficiently compelling to suck you into the images so that the stories are vividly psychologically embedded in those visages. Is it possible, like the way you could be engrossed in a well illustrated (true) story you might read in Vanity Fair and end up—in an attempt to make connections—studying the features of the main protagonist on the cover?

I don’t think it is. The two don’t effectively link up. The reason is they are declared as fictitious. They remain separate, despite the artist’s intentions—and the paintings dominate.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.