Andrew Paul Wood – 11 August, 2019

How is this exhibition re-writing history, aside from highlighting the existence of an artist and provocateur who has largely been ignored for decades? How is this exhibition a “celebration” when it goes to great pains to be objective and critical. It's not this exhibition trying to re-write history at all, but rather the protesters seeking an easy platform for their general sense of alienation and anomie.

EyeContact Essay #32

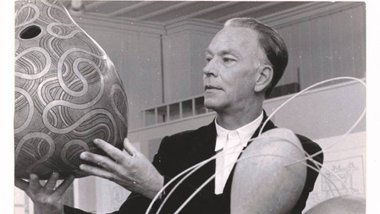

The City Gallery Wellington exhibition Split Level View Finder: Theo Schoon and New Zealand Art, curated by Damian Skinner (off the back of his recent biography of the artist) and Aaron Lister of the gallery, has found itself at the centre of protest and hostility on the grounds that Schoon was a racist who made his career (such as it was) appropriating from Māori culture.

I want to argue that his interests were a lot wider than that, encompassing the Bauhaus, the art of the mental health patient Rolf Hattaway, and pioneering images of mud pools and other geothermal formations around Rotorua. Protest is healthy, voices are to be used, but as someone who dedicated many years to researching Schoon, I consider some of the complaints levelled at him, Skinner and the gallery, are worthy of interrogation. Others are not.

Certainly some of the media coverage seems driven by a clickbait internet model rather than debate. Laurence Simmons’ review of Skinner’s book in Landfall seemed barely to tackle the book at all and came across more as a review of the reviews and pointedly hostile to Schoon. The following line had to be edited when I and others complained: “Another ‘social’ factor entails identity politics. Schoon was homosexual, openly so, and no special sleuthing is needed to winkle out his desires from his art and his adoption of decorative techniques.” Schoon seems to be being set up as a popular bogeyman to project various agendas on.

Was Schoon racist? That rather depends on what one means by that very broad term. He was, at times paternalistic, condescending, made assumptions, pretended to cultural knowledge and prioritised his own agenda at the expense of Māori practitioners. He regarded, and loudly proclaimed, that contemporary Māori visual culture was a “degenerate” (his word) version of its earlier greatness. One might question his word choices (despite being very articulate and fluent, English was still his third or fourth language) and his Dutch forthrightness, but he doesn’t appear to have been hostile to people of colour on the basis of their race.

If anything, he reserved his vitriol for the Pākehā colonial culture in which he was very much an outsider. Importantly both Skinner’s book and the City Gallery Wellington exhibition never shy away from presenting Schoon’s character flaws, the attitudes and approaches that are no longer appropriate—and that’s exactly what they should do. All too often the messiness and complexity of cultural interaction in Aotearoa is rendered down to simplistic and generalised postcolonial narratives that reduce Māori to a monolith and rob them of agency. This is a point I will return to.

For over a century Pākehā narratives have white-washed what we find uncomfortable in the on-going process of colonisation. Really, we need more honesty like this in public institutions so that we can better confront the issues tearing apart the social fabric today. At the same time, we shouldn’t ignore Schoon’s impact on the direction that Pākehā and Māori art has taken (in the latter case, particularly through Schoon’s illustrations for Te Ao Hou magazine)—ironic when the Pākehā art established managed to edit him out nearly altogether for decades. You can’t punish the dead for their sins, you can only contextualise them, which Skinner and City Gallery Wellington have made every effort to do. At this point we need to look at what the protestors themselves say about their motivations.

To quote protest organiser Anna McAllister in Lana Lopesi’s article for The Spinoff, her concerns include that the exhibition will “retraumatise” Māori, “the capacity of City Gallery and two Pākehā men to facilitate the criticism and critical thinking that this kind of artist requires”, and that “that those who have criticised this protest as trying to re-write history have failed to take into account that this is not a museum, this is a contemporary gallery. We aren’t wanting Schoon to be taken out of the history books, we just don’t believe he should be celebrated in a contemporary space, where his views simply do not belong.”

To tackle each of these points in turn, the word “retraumatise” is problematic—it implies that Māori are one collective hive-mind and that they were particularly “traumatised” by Schoon in the first place. It doesn’t sit particularly well with the call for white people to stop treating indigenous groups as monoliths. Putting aside the way such framing reduces recent Māori history to one of passive victimhood and incidentally feeds into colonial divide and conquer strategies, the historical record in fact shows Māori choosing to disregard or deal with Schoon on their own terms as it suited their interests. Māori, it seems, have had nearly two centuries of experience in dealing with cranky white arseholes. So, in 1963, we see Schoon invited to participate as the only Pākehā artist during the first Māori Festival of the Arts at Tūrangawaewae Marae in Ngaruawahia.

Regardless of why Schoon may have thought he was accorded that honour, it was mainly because of his efforts in reviving gourd growing in Aotearoa. Māori knew exactly what they were doing, and if you want an example of exactly how much influence they could bring to bear against Pākehā artists they saw as exploiting them at the time, one need only look at how the Māori Women’s Welfare League comprehensively shut down Ans Westra’s Washday at the Pā publication the following year at considerable expense to the state.

Speaking of the League, it appears some Māori were interested in Schoon’s experiments in pounamu carving, as in the late 1960s or early 1970s we find former League National President, Maata Hirini commissioning a mere from him. This is not the only example of such a commission by Māori as a matter of documented record. Leaping forward to 1992, seven years after Schoon’s death, and the internationally touring Headlands exhibition, Rangihīroa Panoho brought the appropriation by Pākehā artists of Māori visual culture into the spotlight in an essay / broadside launched against Gordon Walters, while noting approvingly that Schoon approached Māori art respectfully because Schoon saw it and not Pākehā art as the only worthwhile art tradition in Aotearoa.

Now, while I’ve always thought this a bit odd given Schoon’s project, in my opinion, was far more actively invasive and appropriative than that of Walters (it was my MA supervisor Jonathan Mane-Wheoki who encouraged me to see Schoon more sympathetically), Panoho is no shy wallflower when it comes to calling out racism when he sees it.

Criticism of Schoon for his touching up and “improving” of Māori rock drawings is on sounder ground—something that can’t simply be dismissed as youthful impetuosity. However had he not so enthusiastically and tirelessly promoted their importance, chances are many more drawings would have been flooded as part of booming hydroelectric schemes, or blown up and bulldozed by farmers and burned in lime kilns to make fertiliser. At the time even anthropologists like Canterbury Museum’s Roger Duff, the man tasked with supervising Schoon’s rock drawing project, believed them to be mere doodles by Moa hunters waiting out the rain.

It was Schoon who invested the drawings with spiritual potency in the public imagination. There doesn’t appear to be a great deal, despite extensive searching, of Māori having much to say about the drawings at all at the time, although I’m happy to be proven wrong about that. Again, emphatically, none of which excuses what Schoon did.

At the very least the situation is more complex than presented by the protesters, which should at once have been obvious if they had read Skinner’s book, or his PhD thesis, or my MA thesis, or multiple other sources on the subject, but their main source of information seems to be Anthony Byrt’s review of Skinner’s book for The Spinoff. I consider Byrt a friend and a very fine and capable writer, but that wasn’t his most thoughtful or informed work. It does beg the question, however, that if the third-hand views of one Pākehā writer can inspire a protest, then why can’t two Pākehā curators, one of whom who has dedicated years of research to Schoon and demonstrated the utmost sympathy for Māori, be capable of putting together this show? Is it not time Pākehā owned their bullshit? A reoccurring refrain from Māori academics and curators is that they’re tired of articulating these issues to Pākehā and that Pākehā should educate themselves. At least since the 1990s, art historians are well trained in the politics of visual representation, postcolonial theory and intersectionality, so we’re not completely oblivious to the nuances.

As for the puzzling formulation that City Gallery Wellington is a “contemporary gallery” and not a “museum” and therefore such a show is outside their mandate, firstly how are any of these terms defined? Schoon died in 1985, hardly an aeon ago.

“Contemporary art” is hard to define, given that it seems to start in the second half of the twentieth century. City Gallery Wellington isn’t a museum in the sense that it doesn’t have an art collection. Te Papa is a museum, but it also shows contemporary art. City Gallery Wellington has previously also shown survey shows of work by artists whose high point was the 1960s, ‘70s or ‘80s. As a criticism it doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny.

How is this exhibition re-writing history, aside from highlighting the existence of an artist and provocateur who has largely been ignored for decades? How is this exhibition a “celebration” when it goes to great pains to be objective and critical (I recommend reading Nathan Pohio’s essay in the catalogue which is far from flattering to Schoon). It’s not this exhibition trying to re-write history at all, but rather the protesters seeking an easy platform for their general sense of alienation and anomie.

Some enlightenment may be gathered from the protesters’ t-shirts. As Lopesi notes, on the front they read “Theo Schoon is a racist” and on the back, “Fletchers supports this exhibition” and “We stand with Ihumātao”. So yes, Schoon was a racist (past tense because it’s difficult to see how he could be racist from the grave) for a very specific given definition of casual, paternalistic, thoughtless racism, as we have seen, not uncommon for the time and still common today.

The reference to Fletchers is a bit strange. Some of the work in the exhibition and the money for the catalogue came from the Fletcher Challenge Trust. A quick google will reveal that the Trust is a charity independent from Fletcher Building, with its own governance, and has been so since 1980. About all they have in common is the name. Perhaps the somewhat forced link with the Ihumātao protest, beyond the general and understandable feeling of Pākehā injustice, is a need to find greater legitimacy given how tenuous some of the Schoon claims are. An actual Ihumātao protest might have been more to the point, as that seems by far the more urgent situation.

Protests in art galleries have been widespread since the Gorilla Girls but have been particularly common in recent years—consider the furore around Dana Schutz’s Emmett Till painting in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, or that surrounding Luke Willis Thompson’s shortlisting for the Turner Prize in 2018. There is an obvious cachet, a feeling of belonging to an international movement.

Personally, I think it’s a great thing that art and art galleries can provoke debates, even angry ones, around such subjects. They are natural places to expect a clash of narratives and agendas, but we still need to show and see the artworks in order to be able to talk about their putative qualities. (Also, McAllister might say she doesn’t want Schoon removed from the history books, but if she actually knew that much about him, she might have realised he was barely in the history books in the first place—because he was openly gay, foreign, scathing of the establishment, extremely difficult socially, and more interested in Māori art while loudly disparaging Pākehā art).

It’s perfectly fine to be critical of, even hostile to Schoon’s agenda—I am myself on many levels—but this exhibition (with its displays unimpeded) is still the best opportunity to discuss any group’s obviously genuinely-felt distress.

Andrew Paul Wood

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.