John Hurrell – 8 January, 2020

I want to briefly draw out Curnow's comments in particular, looking at five or six works in the show, because I'm fascinated by—despite the seriousness of McCahon's life's project—what (surprisingly) can be seen as mischievousness in his practice; the ‘appetite for ambiguity' that Curnow refers to. It makes me wonder if McCahon is teasing; a bit sly; a bit of a scamp? Perhaps some sort of trickster?

Auckland

Colin McCahon in Auckland

A Place to Paint

Curated by Ron Brownson and Julia Waite

10 August 2019 - 27 January 2010

This New Year holiday period is a good chance to have a second prolonged look at the large McCahon show on the top floor of AAG (if you’ve seen it already), or a long squizz if you (inexplicably) haven’t bothered so far. With the recent hefty publications by Justin Paton and Peter Simpson, and great writing by Wystan Curnow in the last Reading Room, and Robert Leonard on his website, there is lots of new information circulating about these works and McCahon’s working process. Websites like MCCAHON 100 are also pretty interesting.

The show is a mixture of well-known and rarely seen paintings assembled from different national collections up and down the country. It looks at McCahon’s time in Auckland, and has three rooms allocated into three decades: the 50s; 60s; and 70 to early 80s. Even if you are a McCahon fanatic, you will find plenty of surprises. We are presented with a wide range of work, and as you’d expect most are on Biblical themes and involve cursive or printed text. There are twenty-five paintings, plus (to add extra resonance) there are the related Wake and the Fourteen Stations of the Cross ‘waterfall’ series downstairs on the ground floor.

Thinking about McCahon’s aims, here are two quite different accounts of his methods of creating meaning through his paintings.

Thomas Crow, the author of a superb paperback No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art—with chapters on Chardin, Rothko, McCahon, Smithson and Turrell—a couple of years ago chatted to Kathryn Ryan on RNZ about McCahon. In part of his interview he said this:

One of McCahon’s constant themes is the difficulty of communication, of people mishearing or misunderstanding or deliberately betraying the sense of the words of Christ in particular. His own desire to communicate and the feeling he wasn’t being understood. He found the most vivid and overwhelming figure for this in the gospel of John in particular, because of Christ’s effort to make himself understood, and continually being frustrated…

Wystan Curnow (BTW an enthusiastic champion of Crow’s book) on the other hand has this to say:

Although he sought, even yearned, for simplicity and clarity in his paintings, qualities many of his reviewers and commentators have found or wanted to find in them, McCahon’s appetite for ambiguity and uncertainty, rejection of closure, is one he never relinquishes. He knows it is essential to the power of his work. He is as much compelled by the need to generate problems as to solve them. (‘Salvation Army Aesthetic: The Politics of Colin McCahon’s “Early Religious Paintings,”’ Reading Room #8, p.27)

I want to briefly draw out Curnow’s comments in particular, looking at five or six works in the show, because I’m fascinated by—despite the seriousness of McCahon’s life’s project—what (surprisingly) can be seen as mischievousness in his practice; the ‘appetite for ambiguity’ that Curnow refers to. It makes me wonder if McCahon is teasing; a bit sly; a bit of a scamp? Perhaps some sort of trickster?

McCahon’s Titirangi (1956-7) painting, an abstraction of bush and sky filtered through a showering cascade of tilted dark green and blue Malevich squares, on one level is about dappled light and bodily immersion, but in coordination with the related French Bay and Flounder Fishing, Night works it can also be imaginatively interpreted as being about an obsessive work ethic and an artist envisaging his future life’s work: a commitment to the production of hundreds of paintings. Maybe even a furtive wink at his own myth construction and growing reputation.

Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian (1961) again has multiple layers and more than a hint of irony. He adores Mondrian for his innovative achievements but also resents the conceptual art historical obstacles his paintings present. The image could be a painting packed in a shallow rectangular box and tilting over. It also could sardonically mock Mondrian’s passionate dogma extolling vertical and horizontal compositional lines as spiritual symbols. It is a cluster of geometrically organised, turbulent, ambivalent feelings.

The Way of The Cross (1966) is a painting rarely seen—a work gifted by McCahon to a convent. It presents Christ’s walk to Calvary (with its traditional Roman Catholic fourteen stations) as a climb along a skyline of hill forms that rhythmically ascend and descend. What is surprising (shocking even) is the use—along the top edge and within the long painting—of the cross pattée shape, a form associated with the Nazi or Prussian Iron Cross. Most viewers will assume that that unfortunate link was not anticipated by McCahon, yet its presence may be intended to confront—to profoundly disturb. One can’t imagine McCahon being oblivious to its connotations, and if he did intend provocation it may be linked to the pacifist beliefs analysed by Curnow in his article. (ibid.13-27pp).

The Large Jump (1973) looks at the notion of the leap of faith and the towering rock formations linked to Muriwai Beach and the resident gannet colony. The fledglings’ first flight jumping off the cliffs is schematically rendered as ‘jumping down.’ The painting here seems to represent Christian believers ‘jumping up’ to a position of certainty that reason refuses to bring. Other works though are created representing a leap across a gap between two towers. Collectively the group of Jump works is about risk taking and conviction, with the dotted (two way) trajectory lines being unpredictable (the height of the end-points) as putative indications of launching or landing.

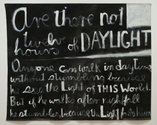

I Considered All the Acts of Oppression (1980-2) is based on sections from the Book of Ecclesiastes, that he quotes in white paint cursively writing on a large black canvas. This work seems different from his other paintings. It is considered to be his last work and the black (unwritten on) rectangle on the right to some may look unfinished—as if he ran out of energy. That ‘blankness’ connects this work to the Jump series (its showcasing of trust), so that we see the void as intended, and perhaps a hint that McCahon was thinking not only of the end of his productivity but also of his own death (an empty doorway?). It is similar in its work/death layering to Are There Not Twelve Hours of Daylight?

When you read it you also see that the text is about absence—of champions of the oppressed; of the living; of plenitude of meaning; of all human achievement. Conceptually it fits in perfectly with the negative space. It’s quite extraordinary. What a way to end.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Ron Brownson’s recent death is quite a shock to the Auckland and national art community, and while all of the ...

Ralph Paine

II. In marked and I think negative contrast, McCahon goes on to claim that today’s painters simply make “things to ...

Ralph Paine

I. Sometimes it pays to listen to what artists say. Not so as to be told authorial truth, but rather ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 9:52 p.m. 10 January, 2020 #

I.

Sometimes it pays to listen to what artists say. Not so as to be told authorial truth, but rather to learn of the paradoxes inherent in artistic autobiography. Paradoxes are not about WILLED “ambiguity” or “mischievousness.” Paradoxes are about a coexistent unity, duality, and multiplicity of meaning, that is to say, they concern the always reciprocal presupposition of different levels of meaning. Paradoxes thus allow for serious attempts by anyone (during different times and for different reasons) at unpacking the AND…AND…AND of meaning: they are essentially non-frivolous and non-contradictory. In this sense, all of McCahon’s words and works (all artists’ words and works) intrinsically hold together a unity of meaning, a duality of meaning, and a multiplicity of meaning.

Here are some of McCahon’s words. They are much quoted ones, and come from the catalogue for McCahon’s 1972 survey exhibition at Auckland City Art Gallery. No doubt many readers have considered these words, puzzled over them, wondered as to their paradoxical nature....

“My painting is almost entirely autobiographical – it tells you where I am at any given point in time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in. In this present time it is very difficult to paint for other people – to paint beyond your own ends and point directions as painters once did. Once the painter was making signs and symbols for people to live by; now he makes things to hang on walls at exhibitions.”

The first part of McCahon’s statement asserts that painters of the “present time”—let’s say, the modern—have no choice but to be “autobiographical.” No choice but to conduct themselves as autonomous beings, that is to say, to operate as self-reflexive genii à la Emmanuel Kant’s The Critique Of Judgement. Alone in their artistic pursuits, they are private thinkers.

In other words, McCahon is saying that the modern, “autobiographical” regime of art actually FORCES painters to act in this manner—and thus, that it’s “very difficult” for them to paint beyond their “own ends,” very difficult for them to paint for “other people,” to paint/point directions for other people. Yet—apparently—this is precisely what painters once did. The next brief part of the statement reads like a lament. Here McCahon is mourning a lost world. What is this world? No doubt it’s a pre-modern one, yet the specifics are unclear.

Elsewhere McCahon speaks highly of “the art of churches”, so let’s assume his lost world is a pre-modern European one. What he appears to lament is the loss of a Medieval world, a world where Christianity permeated every dimension of life, from top to bottom.... From the Pope to the peasantry, from lords and bishops to the mostly ANONYMOUS artisan-painters of that time and region. A time and a region in which painting/pointing directions was an uncomplicated yet passionate and collectively urgent affair.... Or so McCahon seems to have believed.

Ralph Paine, 9:55 p.m. 10 January, 2020 #

II.

In marked and I think negative contrast, McCahon goes on to claim that today’s painters simply make “things to hang on walls at exhibitions.” Now, what’s so puzzling about McCahon’s words is the plain and simple fact that he dedicated his entire adult life precisely to MAKING THINGS TO HANG ON WALLS AT EXHIBITIONS. And, he was extremely successful at doing so. He embraced the modern, “autobiographical” regime of art with great vigour. And reciprocally, it embraced him.

Yet McCahon not only embraced the modern, “autobiographical” regime of art as a painter-thinker, he also embraced it as a curator (keeper), a university teacher, a mentor and friend.

OK, add all this up—the prolific art making, the constant exhibiting, the hyper-success, the teaching, curating, mentoring, and supportive friendships—and clearly we get a McCahon whose artworks—and art-WORK—indeed did provide signs and symbols for people to live by; a McCahon who did point directions for other people—yes, even for “an imagined people,” a nation-state. We get then a figure who very actively (and perhaps AT TIMES with difficulty) helped the modern “autobiographical” regime of art to grow and develop into what it is today. In this sense, McCahon was a partisan of the regime.

Thus: institution-wise, legacy-wise, heritage-status-wise, art-as-asset-wise, autobiography-wise, etc. no other artist or art practice springing from this island region of Oceania/Moana stacks up. No other artist or art practice relates to the modern “autobiographical” regime of art in such a synergistic manner.

However—and for me this is a VERY BIG however—the paradox contained in McCahon’s statement—that is to say, the strange differentiation between his words and his sustained actions—opens up a space for the possibility of there being many McCahons, multiple McCahons. Hence, the coherently autobiographical McCahon lived—and lives on—amongst a swarm of other McCahons—a Zen-Existentialist McC, a Heavy-Metal McC, a Sci-Fi McC, a Pagan McC à la D. H. Lawrence, a Derridean McC, a Hegelian McC, a Rastafarian McC, a Trickster McC, and so on.... My Name is Legion, as it were. Or, as the 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud puts it, “I am another.”

And by extension, no doubt the modern “autobiographical” regime of art which McCahon did so much to help establish here in Aotearoa is also haunted by otherness. In this regard, McCahon’s paintings do not simply represent his life; they are not only his autobiography. Rather, his multiple signatures also mark a radical absence, a fertile void, appear as rapidly executed signs of his departure from the scene. Paradox.

John Hurrell, 12:04 a.m. 1 March, 2023 #

Ron Brownson’s recent death is quite a shock to the Auckland and national art community, and while all of the obits talk about his career as a curator (highlights were Shirin Neshat, A Place to Paint, and Home AKL) no mention has been made of his activity as an artist in the seventies and eighties.

This is surprising because he was very highly regarded, for his films were shown in ANZART in the eighties, Wystan Curnow included his lightbox ‘totem’ of hei tiki lightboxes in the 1983 Sydney Biennale, and Giovanni Intra incorporated a City Group image in ‘Everyday Pathomimesis’ at the University of Canterbury Fine Arts Gallery in 1995--a very large b/w photograph of a ginormous tumescent schlong.

He will perhaps mainly be remembered for his work in City Group, video and photographic projects that often looked at the sex industry in K’ Rd.

Ron would occasionally deny being part of City Group, and I myself received an angry letter asking me to remove individual member’s names from a wall label in the Govett. I believe this was because of his wish for anonymity, or a belief in a strictly collective ethos--and not the need for a factual correction. Fascinatingly, he might end up being seen by future art historians as much more important as an artist than as a curator.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.