JJ Harper – 31 July, 2020

'Fire-lit Kettle', curated by Enjoy's outgoing director Sophie Davis, is meant as a reference to the spark of creativity; the fire that ignites in a creative practitioner when they've realised the potentiality of an idea. 'Fire-lit Kettle' is also a show of all women artists, so the concept of feminized labour is intrinsically connected within—which is very Catholic and trad-wife. Ceramics, craft and cooking are also all large elements.

Wellington

Annie Mackenzie, Ashleigh Taupaki, Georgette Brown, Imogen Taylor & Sue Hillery, Li-Ming Hu, Salote Tawale

Fire-Lit Kettle

Curated by Sophie Davis

19 June 2020 - 25 July 2920

Enjoy’s recently concluded group show Fire-lit Kettle had a title that confused me. I assumed, maybe moronically, that it was a group show of all ceramic artists, or at-least ceramics-adjacent. That is not the case, instead Fire-lit Kettle, curated by Enjoy’s director Sophie Davis, is meant as a reference to the spark of creativity; the fire that ignites in a creative practitioner when they’ve realised the potentiality of an idea. Fire-lit Kettle is also a show of all women artists, hence the concept of feminized labour is intrinsically connected within—which is very Catholic and trad-wife, so I approve as a cottagecore king myself. Although I wasn’t entirely off-the-mark with my first impression either. Ceramics, craft and cooking are all large elements of the art in Kettle.

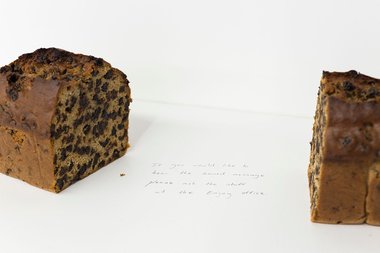

One of the first works you encounter when entering the gallery space is Annie Mackenzie’s Saved Message, which consists of a fruit loaf cut in half and a voicemail recording. Between the two chunks of loaf is a message scribbled in graphite advising the audience that the titular saved message is available to be heard, on request in the gallery office. The message was left for the artist’s mother, by a family friend who had a tense conversation with Mackenzie around the friction between making a living through craft versus the experimentation and freedom (but therefore subsequent lack of income) in art.

Mackenzie is known for her textile practice; the family friend leaving the voicemail is also a weaver. So while there’s a personal relationship that needs to be upkept—there’s also the implication of a professional relationship that needs to be managed. As much as the voicemail is reflective and apologetic, there’s a strenuous nature to it. It feels like a chore on the sender’s end. What the message is really reflective of, is the unspoken pact of the culture industry, to not burn bridges in such a small country, for the fear of losing career opportunities.

While the message focuses on the tension of earning a livelihood through craft/art and the differences in approach between each, the implications are much broader. It’s doubling down on the neoliberal concept of labour being reflective of who you are; employment as the key to life on earth—furthermore that any rejection of that status quo is immoral. Art functions as rejection, while craft functions in servitude. The voicemail made me think of Saidiya Hartman’s text The Plot of Her Undoing:

The plot of her undoing begins with chastity, fidelity, virtue, and submission. It begins with the exchange between the husband and the father, with true womanhood, with her property, with the daughters of the confederacy, with the daughters of the revolution, with the double down on white supremacy, with neoliberal feminism and structural adjustment, with a bid for governance… . The plot of her undoing begins with the advent of the insurance company, with anticipated loss and securitized risk, with the pillage of shithole countries. It begins with a hedge fund, a red line, a portfolio, with the real property transmitted across generations, with a monopoly on public resources, with the flows of global capital. The plot of her undoing begins with the assertion, but I am a decent person, but it is not my fault, but I worked hard for what I have, but I am not responsible, but we could not find a qualified candidate… The undoing of the plot begins when everything has been taken. When life approaches extinction, when no one will be spared, when nothing is all that is left, when she is all that is left.

The flows of global capital, neoliberal feminism, anticipated loss and securitized risk, all these things exist to undermine the project of art, criticality and the ability to be an artist. Anything outside the confines of these undoings is demonised, an ideological tool of the bourgeoisie to artificially create infighting and dissonance between the lower classes. They are strategies to disarm the threat of class solidarity, to disarm power in potentiality of the Modernist and Romantic notions of art as an alternative to a life sustained by traditional forms of labour. Today that labour is, for many, dematerialised into the act of replying to mind-numbing emails and missed phone calls. Saved Message is a rather literal breaking of bread, an extension of relationship made available for public consumption. It positions itself in rejection to these structures but also knowingly plays into them; coming at an impasse as the discourse between craft and art often does.

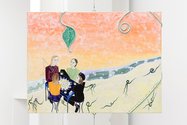

Flanking Saved Message to the left is Georgette Brown’s painting And Holds Us At the Center While the Spiral Unwinds. The work depicts a group of friends sitting at a table together in the orange sunset. Suspended between the floor and ceiling by wire, the painting reacts to the tension of the wire, always slowly, slightly moving. Enjoy’s blurb on Brown’s work describes it as “deploy[ing] an organic, almost psychadelic [sic] language that contemplates ecologies, bodies and internal worlds.” Very hippy dippy. I’m immediately concerned by words like ‘ecology.’ I don’t really care about trees ‘n’ shit. I would prefer there was no such thing as ‘nature,’ only brutalist buildings made to house nationalised utilitarian services like the post office, libraries and schools.

The painting itself is naïve in style, with a glazed ceramic leaf that wraps around the canvas. The exhibition’s roomsheet essay contextualises the creation of the painting during lockdown on Wellington’s southern coast—which was when freak waves battered Owhiro Bay, not far from the artist’s own home. These conditions elucidate the work’s conceptual leanings around “tension, relationships to people and bigger ecosystems.” The installation further illuminates Brown’s thesis on the management of interpersonal relationships; how they are, or should ideally be, representative of humanity’s alliance with nature— for as much as you pull, you also have to give some slack.

Brown’s work makes the argument for balance and harmony within our communities—therein arguing that our communities have a duty of care to the land (née the stolen land of tangata whenua)—but the manufacturing of the very wire that suspends Brown’s work is emblematic of the post-Fordist state of financialized globalist being. The Disney-Coca-Cola-Starbucks hegemony that mines the earth of its resources with the sole objectives of growth and profit, is to blame for the move into the anthropocene, is guilty of causing freakish environmental incidents. We should all litter more because none of us are CEOs; only psychopaths recycle. That’s not to talk down upon Brown’s work, which is obviously aware of these dichotomies. Brown is exploring ecologies in broader, more imaginative ways than myself, being bogged down in gloom and doom. I do however find that ‘love’ and ‘community’ are solutionist answers to not just environmental issues but even interpersonal conflicts. However, perhaps the belief that they can’t be is—in itself—a form of neoliberal indoctrination.

Turning around from Brown’s work you see Imogen Taylor and Sue Hillery’s collaborative mural Sluice. It has a real spark, energy and flair to it, its movement seeming to spring off And Holds Us At the Center pointing you right in the direction of Ashleigh Taupaki’s earthen art sculpture, an artwork collated together from discrete objects, copper wire, harakeke, dyes, māta (obsidian), plaster, found rocks, seashells, glass and aluminium. Developed for Fire-lit Kettle, Toro, piko materially references Taupaki’s own life, made of literal substance collected from areas she has lived and felt connected to; in doing so Taupaki is also exploring matauranga Māori, reconstructing customary Māori knowledge and ways of living under the sphere of neocolonialism.

Next up are Li-Ming Hu’s two videos, Three interviews and Acting / Not Acting. Studying her MFA in performance at SAIC, Hu’s practice is interested in looking at what performance looks like in and out of art contexts. Hu’s life is a perfect candidate for this, having worked as an actress on Shortland Street and Power Rangers. I don’t know exactly what the latter is because I’m not an absolute loser nerd, and I definitely don’t care to find out, but whatever Power Rangers is, it’s quite central in both of Hu’s videos here.

In Acting / Not Acting Hu includes footage of a Power Rangers convention she went to, alongside clips documenting some of her recent art performances and installations to the tune of Donna Summer’s MacArthur Park. The video almost feels like a blooper reel, featuring an interviewer who just can’t seem to say Hu’s name correctly. Hu corrects him until he gets it right, at one point literally winking at the camera. The man is clearly distressed and embarrassed by his continued bloopers, apologising and then asking Hu if her name is “oriental.” Hu is exasperated and the interviewer apologises again, mentioning his autism. The tables have turned and this repositions Hu in an amusingly uncharitable light - of which she is well aware. On the “About” section of her website, Hu writes:

I am a firm believer in the generative possibilities of humor, and see my work as equal parts parody and tribute. If I’m laughing at those I portray then I’m certainly laughing at myself as well. Negotiating boundaries is a constant endeavour - between appropriate and inappropriate types of performance and appropriation, performance and documentation, tragedy and comedy, success and failure, art and life.

The dissolution of the boundary between work and life, especially within the culture industry, is a troubling effect of the financialization of life—of which the dematerialized mediums of performance and video are archetypal. Dematerialised labour under neoliberalism has no clocking-in or out. It requires a 24/7 performance that can never feel like a performance. I find Hu’s mandate of situationism to be a compelling framework, one chillingly indistinct to the reality of surviving in the deregulated free market economy, as Hito Steyerl writes in Art as Occupation: Claims for an Autonomy of Life:

[W]hat used to be work has increasingly been turned into occupation. This change in terminology may look trivial. In fact, almost everything changes on the way from work to occupation. The economic framework, but also its implications for space and temporality. If we think of work as labor, it implies a beginning, a producer, and eventually a result. Work is primarily seen as a means to an end: a product, a reward, or a wage. It is an instrumental relation. It also produces a subject by means of alienation. An occupation is not hinged on any result; it has no necessary conclusion. As such, it knows no traditional alienation, nor any corresponding idea of subjectivity. An occupation doesn’t necessarily assume remuneration either, since the process is thought to contain its own gratification. It has no temporal framework except the passing of time itself. It is not centered on a producer/worker, but includes consumers, reproducers, even destroyers, time-wasters, and bystanders-in essence, anybody seeking distraction or engagement.

The layers of performance in Hu’s other contribution to Fire-lit Kettle, Three interviews is equitably unnerving, as such it’s difficult to take anything Hu says in the video at face value. The title on the other hand is quite literal. Three interviews is actually made up of three interviews. The first is an advertisement for SAIC, which Hu was interviewed for as a student. The second is another Power Rangers fan-conducted interview. The third complicates matters, as it is the only fictionalised interview, improvised between Hu and an arts writer, who is ‘interviewing’ her upon the premise of her nomination for an arts award. The third interview makes you question the authenticity of the whole piece, as up until that point the work has positioned itself to lean more towards being more documentation than art.

Throughout all the interviews there are points when Hu’s eyes light up, where she realises the potential in the moment of the moment to be art. There are other times when it appears she is performing her struggle or the struggle is performing her. Often, all these things are happening at the same time and it is impossible for the audience to position exactly where Hu’s intentions are in the moment. Davis writes in Enjoy’s roomsheet:

Three interviews and Acting/Not Acting share an intentionally blurry—and perhaps irreverent—relationship to authenticity or the notion of presenting things as they happened. They unfold within the often unseen dimensions of creative work, exploring notions of success, failure and the performance of subjectivities in maintaining a practice or playing a role.

Last on the chopping block here is Salote Tawale’s Creep—which is probably the most successfully realised work in the exhibition, as such acting as the backbone that neatly ties a bow on the whole affair. As soon as you enter Enjoy you can hear the echo of Tawale’s rendition of the Radiohead classic. It’s a modest work, but I’m a sucker for clarity and directness. Tawale slowly, creepily lures the audience into the back gallery space.

The irony of Tawale crooning “I wish I was special” plays into previously discussed Romantic and Modernist ideas of the artist’s life. The lyrics recontextualised speak to Tawale’s experience as a diasporic Fijian & queer person. Take for instance the lyrics of the chorus and second verse:

But I’m a creep / I’m a weirdo/What the hell am I doing here? / I don’t belong here

I don’t care if it hurts / I wanna have control / I want a perfect body / I want a perfect soul / I want you to notice / When I’m not around / You’re so fuckin’ special / I wish I was special

This neatly follows on from the themes of authenticity, performance and self-doubt—which take center stage in Hu’s work but are key concepts any artist must grapple with, clear themes across Fire-lit Kettle.

Creep is as much a self-portrait of Tawale as Radiohead’s Creep is a self-portrait of Yorke. The camera is reflected in her pupils, reflective of the tradition within in feminist art of centering the self, away from the “male” gaze in the mode of self-portraiture. In doing so Tawale is not only reclaiming art in the feminist sense but claiming space within feminisms, the canon of which is dominated by white western feminist art.

Fire-lit Kettle evokes for me, several other recent group shows. Notably the also recently concluded CLUB290 facilitated by play_station which also features Georgette Brown’s work. CLUB290 is “a group show of flatmates that looks at the ways we organise ourselves as a young creative community.” I think play_station’s blurb on the exhibition plays down the complexity of the show. CLUB290 is performance art—as a group show. Like Mackenzie and Hu, the exhibition is examining what performance looks like in and out of art contexts, unfurling and meeting somewhere in between. As Fire-lit Kettle explores what exactly are the boundaries between the labour of art and the life of the artist—if there are any to be found, that is—so too does CLUB290. This is evident in the work of Glad We Did That, an ongoing collaborative project between artists Elisabeth Pointon and Robbie Handcock, who feature a video work which acts as a virtual art tour of the artworks in their flat, the titular “Club 290”. Each artist also exhibits individually attributed works in the show. Pointon and Handcock amusingly perform the Glad We Did That project at openings, at bars, in their home and sometimes other peoples’ homes. Where the lines between Glad We Did That ends and CLUB290 begins is unclear, but that’s the project of their performativity.

Although it is all somewhat vain and self-mythologizing—but only in the way that Hu’s work could also be described as such—both contain the self-reflexivity and charm necessary to be successful. I’ll highlight Christopher Ulutupu’s Untitled (Study for Lana del Ray), which dramatises the mundanity of a pot plant’s existence. CLUB290 doesn’t lack self-awareness, it knows its premise is cliquey and is subsequently wry and mocking of it.

Fire-lit Kettle more pertinently reminds me of Quicken at The Engine Room; curated by Caroline McQuarrie and Jane Wilcox and on until the 14th of August. Quicken references the mechanics of photography, tactility and touch, as curator Caroline McQuarrie writes, “Yet a photograph is only made because light touches something which is sensitive to it,” which speaks to the spark of creativity in Fire-lit Kettle. It is also coincidentally a group show of all women, as such the same themes of labour and femininity in Fire-lit Kettle are on display in Quicken. You can feel the energy in the air within what McQuarrie writes of “touch” in reference to Virginia Woods-Jack’s triumphant photograph from the series Take Me There:

It erupts like flame across the water, orange, angry, explosive. It comes from above like holy fire, cleansing the earth. It seeks spaces between things, spreading, infecting. It does not recognise your borders, your boundaries. It has particles you cannot see, it explodes from the heart of a star. It is heat, it is life. It is light.

Excuse this pun but Fire-lit Kettle was an immensely enjoyable show. I’m impressed by the broadness of the dialogues it can open up, conversations between work across disciplines, across exhibitions. Mackenzie and Hu’s work were standouts for me and I’m especially curious to see what they do next.

James Harper

For the sake of transparency, James Harper is a volunteer with Enjoy. He is also an independent art reviewer. He was not commissioned to write this article for Enjoy. [Ed.]

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 2 comments.

Comment

JJ Harper, 11:28 a.m. 28 November, 2022 #

For the record, I want to publicly acknowledge that I retract any tangential positive comments regarding Robbie Handcock in this review. Just in case someone crawling the EyeContact archives gets it twisted.

D F, 11:19 a.m. 20 April, 2024 #

Hilarious.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.