Peter Dornauf – 10 May, 2023

That the dots for the most part seem to be in freefall or dancing about in unsystematic formation, like wandering atoms, can add to the dis-ease as the viewer searches in vain for what is not there, placed and hidden by the artist. On the other hand, the upside is that the viewer can simply enjoy the capricious, erratic deployment, or become, if they wish, co-creator, involved in a kind of Rorschach exercise. Is that a camel, a weasel, or a whale?

EyeContact Essay #50

Was the dot the first mark ever made by the first artist who daubed some pigment on a cave wall or a piece of bark? Just a cursory glance at your standard Australian Aboriginal painting might suggest that that was the case, although apparently the ubiquitous ‘landscape’ dots were a very late addition to the indigenous repertoire.

Yet the primordial spot, smudge and impression does have something of origins about it. Some suggest that it reaches right back into the mists of time when God first wrote the universe into existence with the primeval particle. It is circular and so are the planets, moons, suns, and even the trajectory of their orbits through space, or were until some astronomer spoilt the notion of circular perfection.

Nevertheless, some curvature is always involved. Even black holes, one assumes, are spherical. Thus, beginning and endings partake the form of the dot.

The narrative of human artistic creation involving the circular point begins properly within modern art practice with the pointillists celebrating chromo-luminarism. Further along that history, we find Damien Hirst’s grid spot paintings, evenly spaced, no two colours alike, playing happy painting; though coming with a touch of unease. John Latham did beat him to it, though, in 1961 with his spray painted, Full Stop—albeit it, black in colour.

So, James Ford, neo conceptualist, is in illustrious company with his plethora of dot works. But if you are looking for Hirstian joy, look elsewhere. After Aboriginal sacredness, you won’t find it here. And Seurat, that man of scientific inclination, would not be particularly impressed. Here is no order, logic, shimmer of delight, religious intonation or reference to cosmic perfection.

What we do have is randomness. The placement of the painted circular colours are accidental, aimless, fortuitous. There is seemingly no ultimate purpose to their configuration. If you join them, you’d discover no recognizable shape.

However, if you do happen to find, for example, the face of Jesus, as some people do when they slice a tomato, then for the artist that is part of the beauty of the exercise. But as they stand, they mean nothing, intrinsically, and that is their meaning. Each work sees a similar haphazard and jumbled constitution and any attempt to impose patterns or significance on them will ultimately not come up with some final definitive denotation.

As such, they could be seen as a metaphor for life itself—”spots of joy” (as Wordsworth once said), seen in the simple perfection of circular colours that jostle and float about—greens, blues, reds etc, but no overall comprehensive design or import. Unease in spades, perhaps, or open to possibilities. On the downside, the discomfort is compounded by obscure tags for titles. For example, Offeret, which in Old Norse means something to do with a sacrifice or victim, is a word the artist simply invented, which ironically turned out to possess a meaning.

That the dots for the most part seem to be in freefall or dancing about in unsystematic formation, like wandering atoms, can add to the dis-ease as the viewer searches in vain for what is not there, placed and hidden by the artist. On the other hand, the upside is that the viewer can simply enjoy the capricious, erratic deployment, or become, if they wish, co-creator, involved in a kind of Rorschach exercise. Is that a camel, a weasel, or a whale?

The exploration of the nature of art and the search for meaning, gets a further workout in a second series Ford has generated which begins with echoes of surrealism.

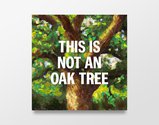

In 1929, not long after the Surrealist movement got off the ground, Magritte painted the image of a smoker’s pipe and then famously wrote beneath it, “This is not a pipe”. Technically he was correct. It wasn’t. It was more accurately a representation of one. Plato would have been pleased, a man impatient with illusions and shadows.

Whether Magritte was wanting to make some metaphysical point, or simply remind the viewer of the obvious, or not so obvious—that the painting was a vision of a pipe, an imagined one, this being standard Surrealist territory—is debatable. However it did open up the whole issue of language and its arbitrary relation to reality; how, in effect, language is the filter through which we look at the world and try to make sense of it, or alternatively, have any sense of it predetermined or compromised.

James Ford takes this area of investigation one step further in his new series of works that are AI dependent. He thereby adds another layer to the conundrum by delving into the nature of the art itself and its representative practice.

For example, his work, This Is Not an Oak Tree, echoes Magritte, but the question of its reality comes under question in a different way. Ford was no doubt thinking of Michael Craig-Martin’s inaugural conceptual piece from 1973, An Oak Tree, when he exhibited a glass of water and argued via the wall label that by some transubstantiation process he had magically transformed it into something else—a tree. We are deep inside the world of conceptual game playing here that interrogates the nature of the real.

Ford approaches the enigma from another angle via simulation that poses the question of ‘fake’ versus ‘real’ using AI art generation. The image on canvas is a machine-generated image of a tree. How does a machine know what an oak tree looks like? This is a mock-up, an object spawned from a thousand alphanumeric inputs that is thus an amalgam of the object. Could this, therefore, be the real deal or something simply generic and thus bogus?

Then at another disconnect from reality, the artist instructs the computer to create an “average landscape oil painting”. What might that be and where is the machine sourcing this material from? And who has decided what “average” might be? We are already at several removes from reality.

Not yet done, it follows that the artist ups the ante in this dance of the seven veils by throwing in a further constraining aesthetic element into the mix, factoring in “tips for artists who want to sell”, advice purloined from John Baldessari. Here the hand of commercialism is brought into play to conflate the procedure, generating some bog-standard image to attract the likes of Mr and Mrs Plastic Bucket.

What we end up with is a kitsch product, which is paradoxically and ironically redeemed because of the philosophical exploration involved. In Perceptual Best Guess, one of those bog-standard saleable landscape digital creations, which presents idyllic cottages placed adjacent to a pretty inlet of blue sea, complete with blue sky and rolling hills, the superimposed title sardonically sums up the picture.

In another twist, the artist plays off man against machine, artistry against apparatus, real versus replication—by carefully and precisely painting the text himself with sufficient exactitude as to simulate the work of a machine. We are well down inside the rabbit hole here, along with Alice. We see the artist having fun with art, reality and all its alternatives, together with its amusing contradictions.

Dots and the AI dependent paintings both deal with the ambiguity of appearance, as does the last piece in the puzzle, a sculptural work that takes that notion and teases us with it. Down the ages warnings have been posted about the corrosive effect of accumulating wealth and the lure of gold. The deception of glittery things has been noted by everyone from Shakespeare to Led Zeppelin, counselling people to check, since “all that glitters is not gold”. Gold is the genuine article, but it can itself be a stairwell to hell. Look no further than the Book of Proverbs—”He who trusts in riches will fail”. Or from the Son of Man himself expounding on how hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of heaven. That life should not focus on acquiring the abundant possessions is something both he and Cynic philosopher Diogenes would have agreed on.

In Thomas More’s, Utopia, in order to encourage contempt for the shiny yellow stuff, citizens of this perfect State were forbidden to wear it, but criminals were forced to— rings, necklaces, and crowns. A clever stratagem.

A similar kind of ruse was practiced in the art world when Italian artist, Maurizo Cattelan, created an 18-carat gold toilet that was installed in New York’s Guggenheim in 2016. He aptly entitled it, America, and 100,000 of them promptly turned up to use the fully operational piece of plumbing. He probably had Duchamp’s Fountain in mind, another satirical piece from the House of Dada. And true to form, the thing was stolen when installed in the bathroom at Blenheim Palace, England.

James Ford follows in the footsteps of such an illustrious art legacy with his appositely constructed sculpture, Carrot, a life-size replica of the vegetable, cast in bronze and gilded with 22 CT gold leaf. Dangling from a golden chain attached to a golden branch, it embodies an interesting ambiguity. On the one hand it alludes to reward and inducement for services rendered without exception, while on the other, conjuring negative images of avarice and corruption. These might include rich King Tantalus from Greek mythology, punished in Hades by being forced to stand in a pool of water beneath fruit-laden trees with low hanging branches that were always just out of reach.

Symbol of ostentation and greed, this piece of bling, a dangling temptation, is comical and witty in its aspect, playing on the verbal pun of carrot/carat, thereby making its point without the tiresome, often laboured, earnestness that can sometimes come with contemporary art.

Carrot is a timely piece given the recent revelations regarding the inequities in our society where the rich pay a disproportionately less amount of tax compared with the rest who foot the larger part of the bill. The notion of the golden carrot reminds one of that other golden fruit, the apple, the one of discord the goddess Iris used to create mayhem among the deities. Fruit and veg wrapped in tinsel therefore have good pedigree and Ford taps into the trope to great effect.

He, in this series of neo-conceptual pieces, has astutely engaged with issues touching authorship, value and meaning and left us wondering, which is the role we expect of all art works of genuine worth.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.