John Hurrell – 13 August, 2009

If I was to write a paragraph about why it could be important I would acknowledge the piercingly hallucinatory quality of the mountainous Canterbury landscape, but also construct an argument about the significance of the peculiar little man sitting on the edge of the platform.

Rita Angus Life & Vision

Curated by Jill Trevelyan & William McAloon

A Te Papa touring exhibition

1 August - 1 November 2009

I can remember vividly when I saw the first touring Rita Angus exhibition back in the early eighties. It was in the old Robert McDougall Art Gallery in Christchurch and everything was dim. (I suspect they mixed up the conservatory lighting conditions of watercolour works with those of oil.) Though there was much wonderful work somehow the show seemed a little curtailed - a bit subdued. For a celebration of an artist who was considered ‘legendary’, I couldn’t really quite understand what the fuss was about.

Now, with this new second touring Angus exhibition, there is no mistaking the range of her talent. The show has real wallop, is brilliantly marketed to a currently much more receptive audience, is bigger, and with the research work of Jill Trevelyan for her recent award-winning biography we know so much more about the artist - not only about her affair with the composer Douglas Lilburn, but also more about her deep pacifist convictions. The woman was fascinating, for a whole lot of complicated reasons - and not because she was a genius, because she wasn’t. She mesmerises because of her faults, not in spite of them.

Some of her work is awful - saccharine and badly constructed - yet even many of these are oddly compelling. They may be technically inept, but they also remain psychologically riveting. There is an awkward stiffness, a lack of fluidity about many of her portraits that is exasperating, especially the portraits of the men in her family, but also in the famous red spencered goddess, Rutu. The later is interesting because of its symbolism, the mixing of its various codes - in spite of its off-putting rigidity.

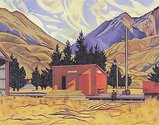

So what do we make of her most famous painting, Cass (1936) - apparently New Zealand’s most loved artwork? That is pretty strange. If I was to write a paragraph about why it could be important I would acknowledge the piercingly hallucinatory quality of the mountainous Canterbury landscape, but also construct an argument about the significance of the peculiar little man sitting on the edge of the platform. Is he reduced in size as an act of revenge for possible male bullying? Is it payback time for her ex-husband Alfred? A pre-Feminist statement. To me that reduction in size seems very pointed. Makes the work more interesting.

Also puzzling are her nude self portraits which inexplicably she did not destroy - even knowing that such intimate images would be gawked at by future generations. The neck seems inaccurately positioned and makes her head sit awkwardly on her shoulders? Like Cass’s ‘little man’ it is not the correct proportion - it’s too small. Is this detail about low self esteem and an intended trope? Was this reduced head intended to make her body look deliberately ungainly? Maybe because she was tall and big-boned Angus hated her height and body shape.

Of course the great portraits are icons, and rightly so. The Betty Curnow image is the perfect masterpiece that will always attract admirers, as will the 1936-7 (‘sophisticated woman with cigarette’) and 1939 (Wanaka) Self Portraits. Likewise the central Otago landscapes (especially the ‘stacked’ one) and jewel-like flower watercolours.

This show needs several visits because it takes time to make connections and examine the relevant explanatory writing. There is a lot you could miss with only one look-in. In Auckland the hang is quite intimate. You are forced up close to the works, unlike say Christchurch where the rooms were much bigger and you could step well back from the displays.

Rita Angus: Life and Vision’s catalogue is beautifully designed and exceptionally practical with its large pages and bold accessible images. There are also seventeen writers contributing to the research of the texts. Yet some of these overlap, and there is insufficient variation in content. The editors should have cast their net wider.

For a reader, having Trevelyan’s own book at hand would help solve that problem, and she is especially good at revealing the happy side of the artist’s life - by quoting her letters. It is easy to focus on Angus’s cranky abruptness with art historians, her tragic breakdown, the miscarriage, and her depressing poverty when she spent money on paints instead of food, but Trevelyan’s biography - now in most libraries - balances that. We hear a lot about the artist at her mental and physical peak, how her peers admired her, and her confidence about her place in this country’s art history.

Trevelyan’s book aside, the catalogue is another story. While it is very informative it could perhaps have included other relevant discussions, like for example, that of watercolour technique. Tony Mackle and Courtney Johnston do write on this subject, but they don’t investigate that recognisable intensity found in her use of this medium for flowers and landforms. Angus was an unusual practitioner and more explanation of how she achieved that unique jewel-like quality would have helped further educate her audience (me included).

Also, Angus’s influences are underplayed, if not ignored. The Barrs on their blog site quite correctly criticised Trevelyan for this a year ago, and glancing at Angus’s images throughout the two publications, artists like Joan Miro, Charles Demuth, Charles Sheeler and Edward Hopper do seem to have played an important role in her artistic growth. This doesn’t downplay her achievements of course, for no one denies art feeds off art. It just celebrates her enthusiasms, and displays how she (deliberately or unconsciously) utilized qualities from other artworks to help fashion her own.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.