John Hurrell – 26 March, 2011

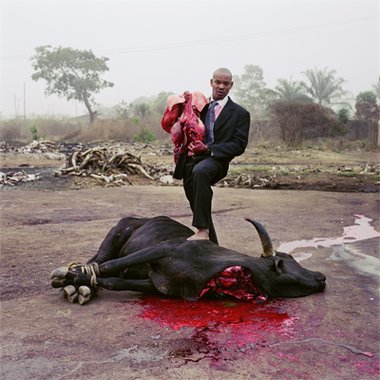

The backgrounds behind the casually posed figures are usually of dumped scrap metal, furniture and piled up detritus. Gory prosthetic wounds and fake body parts abound. Even some of the bloodcaked machetes, swords and oily guns look made of plastic. Now and then something hideous appears that is real, like a brutally slaughtered buffalo with its neck hacked open.

This set of thirty-five Pieter Hugo photographs, toured by the IMA in Brisbane, presents us with the first opportunity to see some African photography since Roger Ballen was at St. Paul Street in 2009. Based on the ‘Nollywood’ film industry in the cities of Enugu and Asaba in Nigeria where many low budget movies for a huge DVD market are written, rehearsed, filmed, edited, packaged and sold often all within one week, Hugo uses the actors and various people he comes across - along with props and prosthetic effects - for his own dramatic static colour images. From the titles that give the models’ names, it seems they pick the accessories and setting. The works seem to be self-portraits as much as directed by Hugo.

These large photographs blend brutal horror and humour in a way that disturbingly confuses atrocity with farce, condescending western media clichés with stinging satire. Hammy but also genuinely hideous. The models he uses are obviously having fun, enjoying the pretence and manipulation of props, but still something disturbing comes through: the distance between life and art in this setting is not as great as might be hoped. Both seem brutal - especially to ‘civilized’ New Zealand eyes.

Yet Nollywood - Hugo’s inspiration - with its mix of urban stories appropriated from Hollywood and blended with voodoo, mummies, vampires, and witchcraft, is despite all this, rich in optimism and hope. Indigenous religion co-exists with Christianity and Islam. The film makers say that they ‘tell it what it is from the people who are feeling the pain’ while the churches (for example) endorse such productions as ‘therapeutic agencies’ for the people who migrate from the villages to the cities searching for prosperity. The use of magic ritual and voodoo is a normal part of that search.

The backgrounds behind the casually posed figures are usually of dumped scrap metal, furniture and piled up detritus. Gory prosthetic wounds and fake body parts abound. Even some of the bloodcaked machetes, swords and oily guns look made of plastic. Now and then something hideous appears that is real, like a brutally slaughtered buffalo with its neck hacked open.

There’s plenty of humour too. One bleary-eyed apprehensive girl has her teeth stitched together with black thread. Or a chubby tousle-haired, sleepy Jesus, wearing a green crown of spiky thorns and lots of gruesome scars, posing with a bunch of non-plussed dust-coated children. The only white person depicted is the artist, menacingly clutching a machete while wearing purple y-fronts, a woollen balaclava, gloves and an ‘et in Arcadia ego’ tattoo under his neck. His image drolly references Poussin’s quoting of Virgil in his two versions of The Arcadian Shepherds (1627, 1637) - ‘even in Arcadia I (death) exist.’

The rawness of this show, albeit constructed and fake (er..sometimes..mostly), is peculiar - particularly when mixed with a kind of graceful symmetry that ends up making these images refreshing. Their tumbledown squalor, rags, wounds and filth (like dirty caked-on grease) we can never be too sure about, but the conventional balancing of standing or seated figures is reassuring. Their placement - a comforting predictability amidst apparent chaos - makes us keep zeroing in onto the detail. To speculate about feasibility and if seeing really is believing.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.