Peter Ireland – 7 July, 2011

Since her emergence almost two decades ago, du Chatenier's imagery has clearly been intimately based on, and querying of, popular culture, conventional notions of identity, beauty and perhaps gallantry, social behaviour such as retail therapy and the ins and outs of social relationships generally. Almost the stance of a traditional moralist - but, in that ironic, apparently Postmodern way, without the bite.

The Rayner Brothers Gallery is a squarish, domestic-sized room about 4M wide and 5M deep with a full shop window on the ground floor of a substantial two-storied masonry building a block and a half off Victoria Avenue, Whanganui’s main street. It’s been open for nearly four years and in that time their enterprising programme of shows has drawn something of a cult following. The brothers’ talent for hosting equals their skill at curating, and sometimes their openings attract crowds in excess of 150, spilling out onto Guyton Street causing traffic to divert. It’s nearly as good as faith moving mountains.

The Rayners are artists themselves, covering a whole range of media, from painting and printmaking to ceramics and photography, and this somewhat catholic spectrum applies also to their taste. Paul trained at Elam and later worked on the Te Papa project before returning to Whanganui to become curator at the Sarjeant for a number of years. Mark’s a late-comer to art but has lost no time catching up, his output being as prodigious as his imagination is fecund. Both have a refreshingly playful and irreverent approach to often po-faced art production which gives their work both zing and sting. This devil-may-care attitude shows up in their choice of other talent too. Unrestrained by big-city anxiety about “the right look” they have a special affection for what’s called “outsider art”. However condescending this term might be, at least it’s a telling contrast to the insider art shown by most metropolitan dealers.

Lest you’re tempted to think so, their programme is anything but a dog’s breakfast. (Although they’d be up to putting together a group show on the subject.) While it’s pretty much a mix and match of the work of local artists, it ranges from solo shows of “serious” artists, through showcasing virtual unknowns to group shows of three to a dozen artists and sometimes featuring exhibitions of commissioned works on a particular theme. Artists from outside Whanganui show here too, with often current and former Tylee Cottage residents such as Lauren Lysaght dragooned into joining the fray. Each exhibition is deftly composed and handsomely installed. It’s a class act, perfectly pitched to the cultural scale of the town - a key to its popular appeal and modest commercial success.

Andrea du Chatenier is an artist with a national profile who works at Whanganui’s Universal College of Learning. Her sculptural work has been seen in most major galleries - recently her Goldenage installation at the Dowse in Lower Hutt - and her photographs have been reproduced in Art New Zealand 108 and issues of Landfall. She had the distinction of her work being selected for the Sao Paulo Biennale in 2004.

Her website profile includes this statement: Drawing from a range of theoretical texts including art history, feminism and psychoanalysis, my figures explore aspects of the human condition, in particular the ironies associated with the human endeavor [sic] to seek an understanding of our place in the world - a definition of Humanness as opposed to Naturalness. A cultural geologist would be able to date this content fairly accurately. But, “Humanness as opposed to Naturalness”? The concept of “Naturalness” - indeed, any concept - would be rather dependent on a concept of “Humanness” rather than dramatically opposed to it, one might’ve thought. Maybe some of those theoretical texts weren’t quite as searching as may have been supposed? In any case, it seems like a re-tooling of the old nature/nurture construct, which is a pretty blunt instrument when it comes to fathoming aspects of the human condition. The theoretical text Giotto based his work on may not be much in vogue right now, but if you’re looking for art historical breakthroughs in concepts of Humanness AND Naturalness, you wouldn’t need to go much further - the depictions of those simple stories still able to refresh and surprise after almost eight centuries.

Be that as it may. Mercifully for all concerned, though, as actions speak louder than words, an artist’s actual work speaks more clearly than even its earnestly-felt theoretical under-pinnings. Since her emergence almost two decades ago, du Chatenier’s imagery has clearly been intimately based on, and querying of, popular culture, conventional notions of identity, beauty and perhaps gallantry, social behaviour such as retail therapy and the ins and outs of social relationships generally. Almost the stance of a traditional moralist - such as, say, Bosch, Goya and George Grosz - but, in that ironic, apparently Postmodern way, without the bite. Toothless, these sorts of observations are reduced to a kind of chewing of the cud, where being seen to make the observation assumes as much importance as the observation itself, as if the situation’s a stage affording the artist an opportunity to take a bow. Goya’s presence in Los Caprichos is as an anger focused on foibles, not an amused smile acknowledging its audience.

Irony without moral content can be little more than a re-packaged, rather condescending sarcasm. As this writer pointed out in a Landfall (202) article in 2001: “The metal of seventeenth century irony has turned out to be a very light alloy in the twenty-first”, and little happening in the past decade has required much alteration in that view. Indeed, metallic content has become all but undetectable in an environment where any mention of irony now is just as likely to trigger the Tui reaction “Yeah, right”.

Rather like modern mokomokai trappers, du Chatenier’s always been interested in the human head, symbolically employing the part to represent a whole. Traditional portraiture has long been invested with the sitter’s “true” personality, or even their soul, but her photographic “portraits” over the past decade have tended to mock this belief, sending up the genre with her Kirk’s Girls - a series of imagined girlfriends for the apparently celibate Captain of the Starship Enterprise - and the later animal portraits where friends donned dog masks. You can easily see where such imagery sits with her larger concerns listed earlier. Always entertaining and mostly interesting, such constructions do risk the fate of the one-liner, however. And the props involved, in all their jiggery fakery, do collectively risk the appellation of “period décor”. A C-grade movie aesthetic has its titillations, but once the frisson has worn off it’s possible to be left yearning for the unaffected simplicities of a Giottoesque wonky hut.

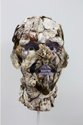

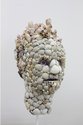

Perhaps the most significant word in the title of du Chatenier’s new show - Denizens of the Deep - is the word “Deep”, or at least its comparative version “deeper”, because this is where she seems to be taking her imagery and themes. The exhibition consists of seven sculptures and six photographs, the 3D works based on life-sized human heads and the 2D featuring the same heads photographed in various watery locations in the rural Whanganui hinterland. Except for one fake blonde wig and some fake teeth, these heads are shorn of their former $2-shop appurtenances, and are covered instead in sea shells - a sort of Arcimboldo in calcium. There are fake glass eyeballs too, but they’re so disconcerting as to seem more real than the natural shells surrounding them, the contrast saving them from an earlier sensationalist banality where they were merely set in awkwardly-carved polystyrene. The arch cleverness has become a genuine spookiness, not so much eye-catching as insistently disturbing. The more you look the more you have to look.

What are these strange heads equivalents of? Us? Not us? (One of them, Denizen - The messenger, has an uncanny resemblance to the Francis Shurrock bust of Christopher Perkins in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.) Previously du Chatenier’s work has suggested a specific time location - even, roughly, for Starship Enterprise - but these new objects cannot be referenced securely to either past or future, a dilemma only deepened by their imaging on the surface of lakes and swamps - are they emerging or succumbing? - the reflections unreliable as to giving hints to movement either way. The show’s title may offer a clue, but, in these multi-faceted works, that Deep is just as likely to be a measure of planetary predicament. This sense of an existential stranding is a long way from du Chateier’s earlier work, the new open-endedness a launching into space William Shatner would be proud of. Oh, there’s still humour all right, but it’s of a slightly guilty kind, without derision, as if to laugh out loud might tip the balance. There may be little suggested movement in these works but they signal a major move forward in the work.

Peter Ireland

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.