Peter Ireland – 7 February, 2013

Beck's new Graphics images have more than a touch of Malevich's abstracts about them in their austere, formal angularity, their beauty more mathematical than sensual. But the photographer has gone one further in the austerity stakes: the Russian spurned figuration but not colour; Beck has done without both. Malevich was a pioneer; Beck has inherited a century's worth of practice. But where does this thread lead us? As all roads lead to Rome, photography leads us back to light.

Andrew Beck doesn’t take photographs; he takes photography. He takes the medium by the scruff of the neck, shaking out its bag of tricks so that all we can be left wondering about is the nature of the bag. He’s not a picture-maker either; he creates visual scenarios whereby the mechanics of picture-making are pared back to the bone. In his own way he’s re-signing the Duchampian urinal, and while his hand is light he’s not taking the piss.

What he’s doing was pretty unthinkable even a decade ago. A confluence of two seemingly unrelated developments has made his work not only possible but inevitable. A relatively new medium, photography’s taken a while to establish such a critical mass as to allow reflection on its individual nature: not just as a pale, try-hard reflection of painting or as the mere handmaiden of industry. Secondly and concurrently, technology has revolutionised the process in the change from analogue to digital, the implications of which will take a while to work out. Ideological positions “defending” analogue or “promoting” digital are signs of defensiveness and rashness rather than contributions to a debate towards any sort of clarity. There’s room for them both - at least philosophically - but the point here is that digital’s arrival has suddenly exposed the assumptions underpinning analogue picture-making for what they are: assumptions. Beck’s quest at the beginning of the twenty-first century is what the Royal Society’s was in the eighteenth, and crisply summed up by its motto: assume nothing.

Ever since George Eastman introduced the Kodak camera in 1888 photography has been dangerously democratic, getting the practice out of the studios and into the hands of amateurs. The advent of digital and the spread of means by which photographs can be taken jointly expand this picture-making capacity exponentially. As they do, avenues of the media play the game of predicting who the first i-phone visual genius might be, their eagerness for a celebrity story blinding them to the fact that the entire playing field has changed location. It’s been said that photographs don’t merely record memories but actually construct memory. Given their present ubiquity, photographs are now beginning to construct reality.

Picture-making generally involves reducing three dimensions to two. In the conjuring trick of suggesting the third dimension photography’s won hands down - so successfully the medium’s been saddled with a connection to “reality” proven to be a very mixed blessing. Beck’s trick is often to introduce a physical third dimension so that these works could easily be confused with sculpture. (Oh, these labels!) But his tricking involves a sleight of hand in reverse. The trickster triumphs by knowing more than the tricked. Beck spills all his beans.

There’s often an unnerving sculptural awkwardness about his objects, but slickness would soften his point. When something as elusive as light’s your subject, pinning it down physically is a bit problematic anyway, but in terms of illuminating the process sometimes an even failed conjurer can be more successful. When you’re letting the cat out of the bag pulling a rabbit out of a hat just isn’t good enough. The six works in this show are all regularly two-dimensional, but only literally. There is a third dimension and it’s in the way these images play with your head. Are these “photographs”? What are they “representing”? Is this guy pulling our tits?

Since its inception, upwardly-mobile photography has been in thrall to its more established, much older cousin, painting. The first identifiable photographic style, Pictorialism, emerging in the later 1880s, was entirely predicated on existing visual art values. Barthes even said that photography was haunted by the ghost of painting - admiring and spooked at the same time. Apples aspiring to be oranges - not an aim conducive to constructing the ” independent art” envisioned by the Commissioners of the International Exhibition held at South Kensington in 1862. Even now, portraiture and landscape photography still owe much to the formal conventions established by more traditional mediums. Thus, in the anti-Picturesque work of, for example, Peter Evans, there’s still the sound of chains being rattled.

Looking back, the advent of photo-realism as a painting style in the early 1970s was a strange reversal. At once a dubious homage and a claim to be legitimising that degree of realism, it hawked a kooky verisimilitude that fooled no one: paintings still looked like paintings and photographs still looked like photographs. But this odd phenomenon may have been a kind of “calling it quits” in the aspirational stakes. A truce made easier by both the demise of Modernism with its abstractionist prescriptions deeming any sort of realism beyond the pale and the arrival of Postmodernism’s laxity around appropriation and quotation, mocking Modernism’s earnest fondness for originality. The conjoined and quarrelsome twins seem to have been separated at last.

So, over the past thirty years photography has found an acceptance - and, consequently, a confidence - permitting it to shed anxieties about status. These days no one’s going to lose sleep over painting appropriating photography and photography quoting painting’s traditions. In fact, observe the current success of Fiona Pardington’s faithless reconstructions of seventeenth-century Dutch still life - perhaps the ultimate “art photography”. Are these works homages to the beginnings of realism in art? Are they instances of the photography you’re having when you’re not having photography? Are they signs of the market’s continuing reluctance to meet the medium on its own terms? In posing such questions these vanitas images, originally about death, start to look pretty lively.

Andrew Beck’s Graphics, however, turns its back on any quoted realism. His quasi-homage is to a visual manner that for almost a century gave photography a relentlessly hard time: Modernist abstraction. OK, the odd photogram got a look in, and if artists such as Rodchenko were “also” photographers, their images might be considered as part of their oeuvre, but apart from these tolerated exceptions, photography’s irreducible connection to realism doomed it to marginal status. Modernist ideology was determinedly avant-garde to the point of denying the relevance of history. How delicious then that the Modernist movement itself has become an historical artifact, and, what’s more, an artist of Beck’s youth is unable to see it in any other way.

Of course, “abstract” photographs abound, but the way in which Beck’s current project examines abstraction itself is a new project, and having photography, of all things, examine it is not only illuminating for Modernism, it’s an even richer seam to mine for a post-analogue debate about the nature of photography and the practice of picture-making. Concurrently with his shows in Whanganui and Paris, there’s one at MoMA entitled Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925: how a radical idea changed modern art. As sources for that radical idea the exhibition’s curator, Leah Dickerman, in her introduction to the catalogue mentions “cars, photography, relativity and the death of god”, proving indeed that hindsight’s a very fine thing. Now we can see photography was in there - pretty centrally too - from the very beginning.

Beck’s new Graphics images have more than a touch of Malevich’s abstracts about them in their austere, formal angularity - there’s a whole wall of the latter in the New York show - their beauty more mathematical than sensual. But the photographer has gone one further in the austerity stakes: the Russian spurned figuration but not colour; Beck has done without both. Malevich was a pioneer; Beck has inherited a century’s worth of practice, a whole constructed tradition where Kazimir saw only wide open space. But where does this thread lead us? Merely to the barren plain of knowing but idle quotation? As all roads lead to Rome, photography leads us back to light.

Where Malevich absolved painting from figuration using paint, Beck is absolving photography from realism using light. Ironically, playfully or whatever, the photographer employs a matt, pitch-black, totally light-absorbing paint on three of his images in Graphics (OMG, is this still “real photography”?) as if to reinforce the difference between the two mediums: a symbolic playing-off of light against dark that’s yet another Beck strategy distancing the prescriptions of realism. Light against dark? Ding, ding, enter Colin McCahon.

From the early 1940s til the mid-‘60s in a ham-fisted take on Cubism, McCahon’s work featured the sort of angular shapes Beck’s employing, but they floated around his surfaces awkwardly until reaching some kind of resolution in his Gate series from 1960 to 1962. A frequent motif was a triangular shape that tended to migrate to the corners, a formal device in terms of image-making having the same relationship to stability as rods in a nuclear reactor. This trick also featured in the repertoires of Hotere and Mrkusich. Of course, anyone photographically attuned will naturally make a connection with the triangular corners used in photo albums, although it seems unlikely McCahon made any association with this practice. But it would be impossible to imagine that Beck hasn’t.

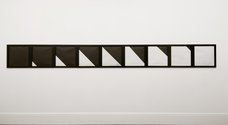

The largest work in the show, the nine square-panelled Nine part progression, is a kind of “apotheosis of the corner”. Liberated from its stabilising function it becomes the subject of the work, and the nature of its progression from left to right (or right to left) is not merely a reference to Gordon Walters’ practice but is in parallel with it: not picture-making but a rigorous examination of coding. Making no concessions whatever to the tonalities that make realism possible, these works nonetheless have an affinity with Hiroshi Sugimoto’s cinema interiors where his shutter remained open for the duration of the movie, the screen registering on later prints as a blank, glaring whiteness. It’s within frames such as these that Beck secretes his photographic histories.

Peter Ireland

![Andrew Beck, Two Corner Cut [High] 2012 Two corner cut [Low] 2012 diptych gelatin silver print on matt fibre paper](/media/thumbs/uploads/2013_02/Twocornercut2012_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.