Peter Ireland – 19 March, 2014

Despite Warhol's famously embracing boredom, Johns fell prey to this condition vis a vis his own work around the turn of the century and consciously struck out in a new direction, signalled by an installation in 2000 involving a domestic sized door and neon. Similarly ambiguous doors featured soon after in photographs that revealed a new conceptual depth that since then has underpinned his developing artistic production.

Whanganui

Paul Johns

Christchurch likes to call itself “most English city”

7 March - 28 March 2014

In recent years it’s become common for a range of artists to incorporate photography in their practice. Modernism’s purist agenda had relaxed enough to allow practitioners to mix their mediums without being thought dabblers, and photography has moved from the margins to the centre far enough to permit inclusion in the range of mediums considered serious. The old walls between painter, sculptor and video artist came down about the same time as the one in Berlin.

A decade earlier, though, in the early ‘80s, a handful of New Zealand artists - mostly identifying and identified as painters and printmakers - were picking up photography and pushing it around. Aucklanders Paul Hartigan, Andrew Bogle and Denys Watkins were among them - even Don Binney was having a go.(1) Further south in Christchurch Paul Johns was not just pushing it around and having a go, it was a central and invigorating element in his art-making. More than any artist in New Zealand at the time Johns hooked into what Warhol was doing: the depths of his conceptual challenges, the superficialities of his visual practice. For perhaps the only time in history lower Manchester Street had a direct line to Manhattan.

Duchamp was Modernism’s Courbet, and Warhol was Pop’s Duchamp. After them, things could never be the same, and whatever individual artists may have achieved visually, conceptually they were just playing rifts on the bass line this trio laid down. Marcel’s readymade became Andy’s Factory product, and the inventive Pole took to the Polaroid as an exemplar of the Duchampian denial of authorship. It was letting the process speak for itself. The SX-70s Johns so memorably produced in the ‘80s remain fresh and surprising - and largely unknown. Only Jane Zusters - with, for instance, her truly iconic Portrait of a woman marrying herself of 1978 - came close to matching his conceptual achievement. Last year’s Warhol show at Te Papa included several original Polaroid portraits, and whether Paul stacked up against Andy or the other way round remains an open question.

Despite Warhol’s famously embracing boredom, Johns fell prey to this condition vis a vis his own work around the turn of the century and consciously struck out in a new direction, signalled by an installation in 2000 involving a domestic-sized door and neon in entitled White Light, a reference to Lou Reed, so the Warhol connection was not entirely broken. Similarly ambiguous doors featured soon after in photographs under the general title of A Perfect Childhood, shown at McNamara Gallery Photography in April 2002. These works revealed a new conceptual depth that since then has underpinned his developing artistic production.

Johns’ photographic practice has never been pure. In the early ‘80s purists sniffed at the use of Polaroid, looked askance at his collaging of them, and later, in the 2000s, doubted the intent of his staged imagery. Was he a “real” photographer, or just an actor stalking about, looking for the main chance with a camera? In the past decade he’s been roasting the Modernist chestnut of the image speaking for itself, broadening his practice into that area of photography intimately concerned with memory, the world of the photograph album and its electronic equivalents where nothing speaks for itself. Rather, that world’s voice is more of an inter-connected chorus of cries and whispers.

One of Anne Noble’s more potent productions - which has had little notice since it doesn’t involve any of her own photographs - was 1998’s Little Book of Relics, a folder containing 8 postcards reproducing a wide range of schoolday memorabilia she collected, part squirrel, part thief, during her boarding school incarceration, she herself describing them as “an odd mix of residue and buried whimsy.”(2) While the Little Book may not strictly be part of her oeuvre it’s part of her being, and this biographical radiance illuminates Johns’ work even more than hers.

Later last year, he joined Japanese photographer Lieko Shiga and Belgian film-maker Francis Alys in an Adam Art Gallery show called All There Is Left, the work exploring connections between loss and memory in the wake of catastrophic natural and political events.(3) An aftershock of the Canterbury earthquakes has been a veritable tsunami of photographic books and exhibitions recording the aftermath, a strange interface of survivors needing to tell their stories and our more comfortable interest in hearing them. Three years later things have settled, most of the stories told and the need to tell them ground down by unresolved insurance claims and the numbing drudgery of enduring day by day unrepaired habitation. The shock subsiding, there’s a more introspective and considered approach to the disaster emerging, and Johns - typically - is something of a pioneer in this transformation.

There were a number of superficially unremarkable Johns’ images in the Adam show depicting wrecked and surviving inner-city buildings where he had lived. But their place in the exhibition was contingent on a number of non-photographic items the artist had either selected from his remaining archive or had made specifically for the installation. One of them was a yellowing newspaper report of a 1936 production of Modern Times at the Odeon Theatre in Tuam Street, right next door to the building Johns lived and worked in at the time of the major quake, both buildings now demolished. He discovered that his ninety-six year-old mother had danced in the 1936 production, and his contribution to All There Is Left was a meditation on these connected shards of memory. As with the other two artists, his work was a reconfiguring of objects and images in an attempt to forge some coherent sense out of personally destabilising destruction. This process translates personal memory into public commemoration, rather as single bricks come to make a wall, or the individual names of the fallen add up to a constructed war memorial.

Another piece of paper is at the heart of his current show at McNamara Gallery Photography. In this pretty basic home-made, post-war scrapbook made of brown wrapping paper there have been stuck down - by the artist’s mother, presumably - several dozen photographs and article headings from The Press‘s part in Canterbury province’s proud commemoration of its first hundred years in 1950. One of the headings, Christchurch likes to call itself “most English city”, being also the title of Johns’ Whanganui show. From the many images in the scrapbook the photographer has selected four depicting constructions best illustrating that Englishness and what it stood (and may still stand) for, and has photographed them again this year: the Bridge of Remembrance, the Anglican cathedral, the early pioneers’ sod cottage and the Great Hall on the old university site. These four images, matted and framed in a vaguely 1950s’ style, are paired on the wall above a double spread from the scrapbook. Three of the constructions depicted are presently under reconstruction and the ultimate fate of the cathedral has yet to be decided, its present situation a powerful symbol of the unresolvable dilemmas braiding the business of memory and commemoration.

It’s a spooky coincidence that at the time in New Zealand’s history when our focus is gradually turning from Europe to the Pacific, Nature has callously wiped most of the physical manifestations of that “English city” off the face of the Canterbury Plains. No matter how much reconstruction occurs, any further claim of Englishness cannot be sustained - even if the will for it be there. That Christchurch has gone forever. But in the subjects of the four photographs Johns made - his choices in all likelihood unconscious of the following implications - there are possibly hints of other things that may well be in danger of disappearing too.

The Bridge of Remembrance commemorates those men and women who, mostly willingly, went off to war and never came back, the structure another powerful symbol, this time of the “ultimate sacrifice”. Perhaps citizens in earlier times were more naively susceptible to the will of politicians and the geo-political map so much simpler that prime minister Savage’s declaration in 1939 “Where Britain goes, we go” now sounds mildly ludicrous. But, on the other hand, there may have been a greater sense of a community spirit then, where practical co-operation could lead to complete selflessness in extreme situations. One suspects conscription would be required now, and even then the majority might be excused on medical grounds. Mercenaries may be required - a sober thought when crowds of young people will soon be gathering at Gallipoli to commemorate our tragic part in the Great War.

Even as the First Four Ships were arriving at Lyttelton in 1850 to establish a specifically Anglican settlement in Canterbury organised religion was being undermined by a new, more rigorous theological scholarship in Europe. While the stresses of contemporary life and a growing materialism seem to be provoking some sort of yearning for the more spiritual aspects of existence, church attendance continues to decline dramatically in the West. In terms of the values now prevalent at the heart of cities, perhaps the most appropriate building for the centre of the Square might be a re-located Casino.

Life was hard for the early colonists, and while in the first years they “made do” with A-framed huts and sod cottages, they aspired to material improvement and collective progress, certainly with personal gain in their sights, but driven too by degrees of idealism and hope and for a better, more equal society. The unimaginable geological forces playing in the Canterbury quakes caused less destruction socially than the market forces ideology of the 1980s.

Pioneer idealism had perhaps its greatest focus on belief in the value of education. Canterbury College was established only 23 years after the settlement had started from scratch, and while it’s easy to scoff at the Oxbridge pretensions of the toy-town Gothic Revival buildings, they represented a genuine commitment to knowledge and scholarship. No doubt this lofty aim remains part of the university’s vision statement, but, just check it out with the teaching staff and those in associated research institutions. Some of those old English values start looking not too bad.

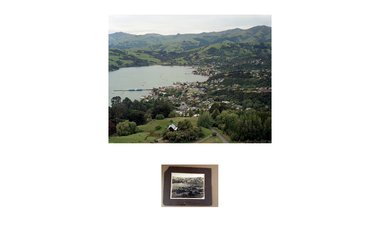

In 2005, when Paul Johns had the Tylee Cottage residency in Whanganui, he acquired a slightly battered original Jessie Buckland photograph of Akaroa in a local Hospice shop for $2. What intrigued him most was the photographer had signed it with her name, the location and the precise date. In the McNamara exhibition this object, encased in mylar, rests on a small shelf beneath a large Johns’ photograph of the Banks Peninsula town taken from the same location exactly 101 years later to the day. This act of memorialisation and commemoration is backgrounded by the artist’s statement: “Since the Christchurch earthquakes I have decided to make use of what I have left in my possession. As insignificant as the items may appear, they start and tremble, they call us (me) by our (my) name, and as soon as we (I) have recognised their voice the spell is broken. We (I) have delivered them: they have overcome death and return to share our life.”

Johns’ gift is two-fold: firstly, he instinctively recognises the memorial power of photographs; and secondly, his conceptual range enables him to transcend the narrower borders of the medium to construct scenarios that not only reinforce commemorative associations but set up poles between which these associations shimmer with a resonance like the humming of telegraph lines - a resonance suggesting the connections between the poles more strongly than the specific instances themselves. More than any other visual art form photography resembles a tribe of imagery, and the interconnectedness it shares with the Maori concept of whakapapa is unique to it, and in the hands of a photographer such as Johns is manifested profoundly.

Peter Ireland

(1) In April 1981 Real Pictures Gallery in Auckland had a show entitled Photographs by Four Painters (Binney, Hartigan, Watkins and Tony Fomison) which was reviewed by Gordon H Brown in Art New Zealand 16, Autumn 1981, p.23. Brown observed that “In recent years the interaction between photography, on one hand, and painting, sculpture and its allied activities on the other has developed in complexity to the point where a clear delineation between photography and the other visual arts is very difficult to make.” Brown himself has been a remarkable photographer since the early 1950s and is yet to receive his due on that score.

(2) See this writer’s review, Landfall 197, May 1999, p. 133.

(3) See this writer’s review, Loss and Memory, EyeContact, 31 October 2013

Recent Comments

steve austin

Thanks for this review. I missed the show, and appreciate your perspective. Every work I have seen of his has ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

steve austin, 8:42 p.m. 27 April, 2014 #

Thanks for this review. I missed the show, and appreciate your perspective. Every work I have seen of his has sustained my curiosity, sometimes over a period of decades.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.