Sophie Violet Gilmore – 29 April, 2014

There is something considerably more challenging about these works. It is impossible to decide whether they are really detached and vacuous, celebratory of their audacious visual style and concerned with little else, or if they offer some sort of critical commentary on the state of art and taste. The subtle reference to art history in the titles of the sculptures seems to say that they do.

Some years ago I can remember going to an artist’s talk that Reuben Paterson gave at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, when his work, When the Sun Rises and the Shadows Flee - a kind of sequined tapestry depicting a tropical sunset - was a part of the Beloved exhibition, and he was a stunningly articulate and thoughtful speaker. Now much later, in In the Company of Animals, his latest exhibition showing at the Milford Gallery, these qualities are still very much in evidence. The show, made up of flamboyant and captivating artworks, all of which feature his trademark love of glitter, somehow this time seems harder hitting.

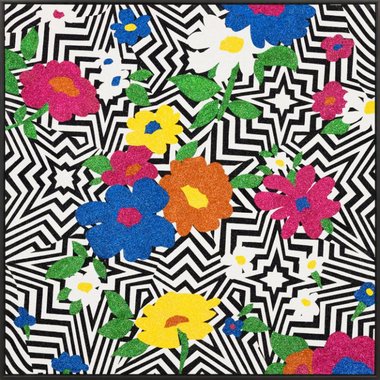

Most of the works are paintings (if they can be called that?) in which polymer and glitter are stuck to the canvas. One purely floral work, a flurry of 70’s brown and chartreuse flowers of indiscernible species, is reminiscent of the wallpaper in most cribs in New Zealand. The glittery surface works as a reflection on the nature of memory: its iridescent shimmer shows the magical quality which nostalgia can invest in mundane images. The flowers serve as a point of exploration for the rest of Paterson’s paintings, in which their forms and colours surprisingly transform.

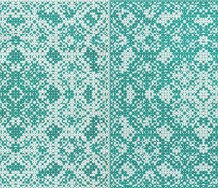

Aside from this one initial work, the other paintings all feature monochromatic, geometrical compositions. In some, such as The Nebula NGC in Scorpius (the painting a bear sculpture is looking at) the tessellation of the monochromatic forms works in striking contrast to the (almost) organic flowers which float like psychedelic apparitions. In Nebula Flaming Star, the flowers have been reduced to their most basic form, composed entirely of exuberant colour in a Warhol-ish fashion.

In other works, the monochrome forms are used entirely to their own effect. They recall the work of the great op-artist Bridget Riley because of the disorientating optical experience they offer, with the crucial difference that Paterson’s works, rather than swallowing the surface in continuous patterning, have a definite centre. At first glance they remind one of kaleidoscopes, but surprisingly, they are subtly asymmetrical, making this comparison questionable. The shapes, rather than folding out of each other, seem in tension.

The monochromatic forms are mesmerizing vortexes which drag the eye forcefully towards an indeterminate centre. They seem to present a uniquely psychological space; the dream sequence of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic Vertigo comes to mind, as do Don Quixote’s windmills. The opulence of the glitter adds playfulness to the works, but there is something about them which provokes anxiety.

Laocoon, a series of three sculptures of snakes (displayed on mirrors, a technique which seems to have become popular in recent times) stands between these paintings. The use of glitter is enjoyably fitting, giving a vivid slipperiness to the snake’s skin. The title perhaps references that extremely famous sculpture, Laocoon and his Sons, in which the unfortunate subjects are crushed to death by sea-snakes, although the reasons for this are pretty mysterious. No sense of agony, or indeed any sensation at all, is created in the viewer by these sculptures. Maybe the title is supposed to be ironic. (Or does it reference the famous Clement Greenberg essay, in which he argued to the inevitable move of painting towards “pure” abstraction? Paterson’s paintings are definitely not pure).

Standing in the entrance-way of the exhibition, the viewer is curiously presented with the back-end of the sculpture David, a gorgeous, two meter tall bear (according to the Biblical story, David battled and killed a vicious bear, but this bear seems very friendly). The bear stands as if in contemplation in front of a painting, amazingly life-like, possessing an enchanting sense of animation in the slight contraposto of its body, and the awed, cross-eyed look on its face. The irreverence of the artwork (a bear couldn’t look at a picture) gives way to seriousness (why couldn’t it look at one?).

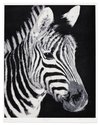

Animals are important to the collection in the way that they comment on the weirdness of the art experience. Prayer, a print of a Zebra, (the composition of which is unusually portrait-like) works with the monochromatic zigzag patterns featured in most of the works to show the patterns as abstracted from nature, yet somehow becoming completely unnatural. The titles of these works - as names of flowers, such as The Dandelion - are also telling. Does Paterson mean to suggest that the art experience, as entirely peculiar to humans, is a sign of our total divergence from nature? Or is it just an entertaining joke?

Also Paterson’s ongoing interest in the camp aesthetic is prevalent in these recent works through their stylization, theatricality and knowing artifice. Yet there is something considerably more challenging about these works. It is impossible to decide whether they are really detached and vacuous, celebratory of their audacious visual style and concerned with little else, or if they offer some sort of critical commentary on the state of art and taste. The subtle reference to art history in the titles of the sculptures seems to say that they do.

Paterson, after offering this cohesive, thought-provoking and just plain pleasurable Dunedin presentation, is about to complete a three month residency in South Korea. This follows stints in France, Rarotonga and New York over the past several years. I’m sure they’ll love him.

Sophie Violet Gilmore

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.