John Hurrell – 15 May, 2014

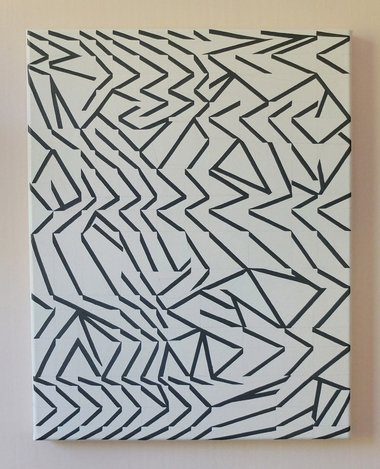

Here the thick lines look like strips of tape, and form sweeping clusters of carefully aligned vectors. Some flow as if in a tumbling mountain stream or waterfall, while others exploit the top lefthand corners of each modular unit, where Foote has left negative gaps that subtly pulse. Sometimes rows of these flip over to make rows of negative righthand corners. There is a very cleverly structured musicality at play.

Upstairs in Two Rooms in the long gallery (and also adjacent storage room) is a collection of Selina Foote’s intimate but complex small paintings, sent to Auckland from her current abode in London. Her stylish fragmented images on taut silk are well known now, having been seen in Kate Montgomery’s 2011 Prospect, The Chartwell Collection (at AAG) and various shows in Sue Crockford.

Much of one’s appreciation of her work depends on the light. Daytime is radically different from evening when it comes to detecting chromatic nuances and matched tones, and Foote‘s delicate angular grids have to be carefully attended to. The translucent support allows the shadowy wall to peek through where paint has not been applied, creating a wispy space upon which the network of shapes float. However in this show she also uses canvas, and so when she paints over the whole surface it looks slightly coarse, almost like a mildly textured hessian.

As is often stated in her shows, Foote starts with a reproduction of a historic painting, usually a portrait (this time from Manet or Rembrandt) from which she makes a drawing, accentuating certain formal aspects of the composition (what she calls ‘gleaning information’. She then uses these elements (‘the drawing produced as a response takes(s) on the role of a material, a tool for the painting process’) as a means of improvised riffing, taking the image somewhere very different from the source. Obviously knowing the precise details of her trajectory doesn’t matter because the procedure isn’t rigidly formulaic. The final image isn’t tightly linked to its origins and not rigorously determined by them. The historic source is only a way of kick starting the process so that a satisfactory image is eventually arrived at.

Although there are plenty of references to contemporary modernist painters like Robert Mangold (outer columns topped with a lintel to form an arch) and Elsworth Kelly (Parisian shadow drawings) in these works, Foote’s inventiveness lies in her understanding of the grid and how to play with its modular properties. Especially impressive are the works using ‘chopped up’ black lines scattered within the matrix - works like Astruc, Trip, Untitled and Untitled III.

Here the thick lines look like strips of tape, and form sweeping clusters of carefully aligned vectors. Some flow as if in a tumbling mountain stream or waterfall, while others exploit the top lefthand corners of each modular unit, where Foote has left negative gaps that subtly pulse. Sometimes rows of these flip over to make rows of negative righthand corners. There is a very cleverly structured musicality at play.

Other works feature rows of tremulous quivering triangles, their vibrating tips a sort of collectively directed antennae - but not holistic like Bridget Riley. No row or column runs continuously from one side to the other. Instead there seem to be juxtaposed blocks of saw-tooth triangles, each with its own character or personality and positioned out of sync with its neighbours. There are also hybrid paintings, pale triangles blended with balanced ‘doorways’ of vertically parallel black lines that seem to allude to the stretcher.

Foote is obviously fascinated by scattered shardlike forms that alternate with negative space to generate in total a flickering (and emotionally volatile) effect. Often - as pointed out - this bristly restless field is compositionally reined in with compressing lines near the sides, or slabs of muted background colour, a tightening rectangle within a rectangle; a swarm of seething angry spikes - perhaps resentful of their generative parents - that needs calming down, collecting, and returning to the centre.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.