John Hurrell – 4 June, 2014

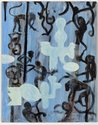

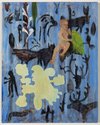

Vertical totemic sentinels hover in the jungle undergrowth, only to disappear much later when inverted and upright geological forms, botanical experimentation, more austere ecosystems and a less saturated palette, take over. We see rhythmically imprecise marks dominate as filmy pattern, caressed vines that could be iron gates, exquisitely drawn monkeys that scrutinise all who enter.

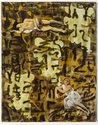

Now exhibited fifteen years after they were made, these Barbara Tuck paintings - with a title borrowed from a Michele Leggott poem - are positioned between the Archipelagos series that Tuck exhibited with Peter McLeavey in the mid-nineties, and the sequence of nine yearly series, starting with Monkey Business (2005) and finishing with Ka Ecologies (2013) - that Anna Miles has since presented. In other words, they come between the shaped arabesque aluminium supports and the compositely ‘landscaped’ square panels. Created in 1999, they are rich in ciphers that reference past works (thin waxy paint, dappled jungle pattern) and future (more implied narrative, rectangular format).

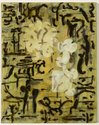

One can understand Tuck’s reticence in exhibiting these hot on the tail of the Archipelagos. They are domestic sized and intimate, as if pages of an experimental notebook where ideas are tentative; even though compositionally they are not reckless. They superimpose shapes from the Archipelagos onto fields of what ostensibly seem to be Pencklike forest squiggles or big cat pelts. The background’s subtlety reveals itself slowly, to be more like motifs from a wrought iron gate with animal and entwined vine silhouettes.

At the Anna Miles Gallery there are two groups on opposite sides of her space: the six canvas, green and brown suite of Iris Gate, and five, mainly grey and blue, individual works. Not only are the earlier, convoluted ‘template’ silhouettes much in evidence but also small Biblical figures and putti quoted from art historical sources like Poussin. They float over the pictographic ‘gate’ lines, locked over and under the pictureplane. Behind them are various animals like deer and monkeys, or a large blackbird head, that could be talismans or (like Hammond) human hybrids - from the ‘divine’ (not the natural) world. The historic painting references seem to be a European foil for the ‘template’ flower/island shape.

Hammond’s presence is strong here, peeking through the soft translucent brush strokes and feathery daubs. Vertical totemic sentinels (related to the shags) hover in the jungle undergrowth, only to disappear much later when inverted and upright geological forms, botanical experimentation, more austere ecosystems and a less saturated palette, take over. We see rhythmically imprecise marks dominate as filmy pattern, caressed vines that could be iron gates, exquisitely drawn monkeys that scrutinise all who enter. Overall, there is a sense of a frayed netlike grid, scruffy Paul Klee glyphs with a tropical chroma.

Because Tuck had just returned from a trip to the UK and Europe when she began these works, we can see traces of some of the museums she visited, allusions to the paintings that excited her. Over the next five or six years she then changed her focus to something less luxuriant, zeroing in on new drier types of climate, exploring different more temperate varieties of landscape, and investigating other forms of composition.

So with this now exposed series, was Tuck sensible (in hindsight) in not exhibiting them? Was her caution wise - perhaps an excessive failure of nerve - in not trusting her audience to recognise their inherent value? Or, did they have no value, and did she think these works were only an intermediary path to somewhere else, and only important because of where they led?

I think it is great to see these, but best in mental conjunction with Monkey Business, not without. (Though they do work in isolation, having a lot of visual appeal.) They are unresolved investigations - experiments - explorations in intuition and logic, juxtaposing several tentative possibilities for research. Later on, out of these, the artist opened up some options and closed down others. Perhaps she was inspired by the Australian artist William Robinson to explore spatial ambiguity via fragmented landscape, taking it far beyond his whimsical cuteness and sweetness - part of that gravitas coming from her square format, emphasising edge, as in her ‘template’ works. A fascinating development.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.