John Hurrell – 30 March, 2015

Krunglevičius presents a series of questions and answers on two screens (the left for enquiries; the right for replies), scrutinising the methodology of persuasion, which this work seems to argue, might be a form of trickery. These are techniques through which the interrogator attempts to ingratiate themselves with the questioned subject, and break down through a sort of systematically structured ‘charm', any resistance to making a detailed confession.

One of the hits in the last Sydney Biennale, the nineteenth one that was directed by Juliana Engberg, was Lithuanian artist Ignas Krunglevičius’s Interrogation, a work which is now being presented in Te Tuhi.

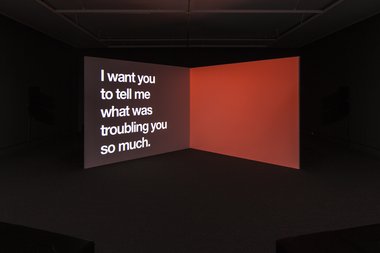

You can hear it in the building long before you see it. It has a hypnotic pulsing disco beat that seems to rarely pause. This installation, with its carefully angled double screen, meticulous (but changing) lighting, nuanced soundtrack and visually overpowering text, deals with police techniques of extracting information from accused prisoners. It demonstrates methods that attempt to gain a prisoner’s trust - a prisoner who may (of course) be innocent, lying, confused, and forgetful. In most cases they will be stressed and vulnerable.

Krunglevičius presents a series of questions and answers on two screens (the left for enquiries; the right for replies), scrutinising the methodology of persuasion, which this work seems to argue, might be a form of trickery. These are techniques through which the interrogator attempts to ingratiate themselves with the questioned subject, and break down through a sort of systematically structured ‘charm’, any resistance to making a detailed confession. These are carefully crafted ‘means‘ aimed at achieving an ‘end’ that will hold up in a court of law.

Here is a link to an animated video version of this questioning that Krunglevičius has constructed out of research from police files. Looking at it on your screen is nothing like the overwhelming experience of sitting on a bench in the dark Te Tuhi space, close to the ‘hinged’ double-screen with its blinding stroboscopic sans serif letters, intensely coloured ‘blank’ rectangles and beautifully modulated, but loud, insistent soundtrack.

There are several stages to the interrogation. First there is the reciting of the five Miranda clauses of stipulated legal rights and option of legal representation (“You have the right to remain silent etc.”), then there are questions about the prisoner herself (identification, physical attributes) where the questioner strives for a form of intimacy by addressing the prisoner by her first name and gradually leading into vital questions via ‘casual’ or ‘informal’ phrases like “(I’m) just curious how…” or “We’ll kind of pick up from…”

Then the policeman starts asking for specific details concerning her relationship to the victim (in this case, the accused’s husband, who died from shotgun wounds) prefacing them with “I know couples are going to have squabbles, that’s typical…” After receiving repeated replies of “No comment” and “I don’t know”, he decides to move on to another phase of psychological pressure:

“Mary, let me explain…. We can’t change the past and everything that has transpired up to this point is history…I don’t know you…but from this point on you can control your destiny…you need to think about your girls, the baby, yourself…”

To this the accused replies, “I can’t right now… I feel you have genuine concern.”

“I know a lot of things can happen between people, and it is tough being married these days…I mean society has made it tough…and there has got to be a reason that these things happened, and there is only one person that knows and that is you…but it is your life…”

“I just can’t find the words right now.”

“Just go through it step by step and tell me what happened.”

“I just can’t right now.”

“It seems like it’s not real, right?…You agree, we can’t change the past?”

Eventually the exhausted prisoner suddenly admits to firing at least two shots, so the lethal injuries might not have been just an accident, and perhaps not spontaneous. At this point the prisoner seems to have realised what she has said, for upon the questioner trying to get some indication of her motivation (“This is your chance to help yourself…”) she refuses to say any more.

This is a fascinating work, one that is very physical in the way gallery visitor is immersed in its claustrophobic sound, text and movement - and intriguing in what it exposes. In its interrogation of the interrogators it doesn’t judge (these are people doing their job) but it certainly makes you wonder about how a lot of court evidence is obtained, and if you would organise things differently.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.