John Hurrell – 23 August, 2015

There is also an element of humour here, displaying bungled writing mistakes as art when normally they are kept hidden or politely ignored. It seems sadistic (picking on a child) and not say (as was common in exhibitions in the eighties with the rise of theory) scrutinising an adult's correspondence when looking for psycho-analytical content (parapraxis). The writing (long before fountain pens) looks so spidery, so nervous, so vulnerable.

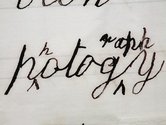

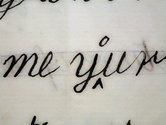

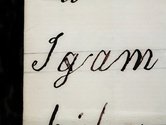

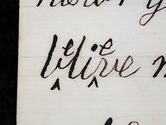

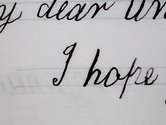

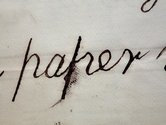

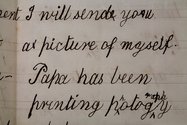

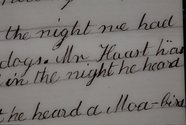

For Fiona Pardington’s first exhibition at Starkwhite (since leaving Two Rooms), her well known images are upstairs in the stockrooms while the more recent work is downstairs, in the office and large gallery. There, nine heavily framed photographs present enlarged images of cursive handwriting, documented samples from the correspondence from early Canterbury settlers, in this case, Arthur, son of Dr. Alfred Charles Barker (1819 -1873), the ship’s surgeon on the Charlotte Jane. The blown up pieces of text - often with spelling or grammatical errors and corrections, or smudged with fingerprints - come from his letters to his uncle Matthias, written in the 1860s.

These enlargements reveal the thinness of the lined paper (you can see shadowy traces from writing on the other side), and the coarseness of the scratchy or smeared quill marks. Though much larger, Pardington’s documentation of decontextualised marks on paper is reminiscent of Richard Maloy’s photographic recording of paint-encrusted student desk tops, or toilet paper sheets. The translucency of the paper is just as important an element as the rows of wobbly diagonal and looped ink lines, and historical content such as the occasional references to personalities like Buller or Haast (naturalist friends of Dr. Barker), the boy’s sporadic observations of bird and plantlife and his father’s interest in photography (he was a significant figure).

With the written content, the titbits of experienced ‘real time’ information become vivid as it is described, and that is part of the show’s fascination. The impact on the reader’s imagination. The other element is Arthur’s learning process, where he (obviously very young) is trying to be tidy with his ink and nib, attempting to spell correctly and present thoughts in a coherent manner. Pardington is attracted to his scripting mistakes, mesmerised by both his grammatical botch ups and corrected additional letters added over the top.

Beside the linear graphic quality, the horizontal composition of spindly diagonal lines, there is also our guesswork around the artist’s cropping. Apart from figuring out how single intact words might fit into an unseen sentence, there is the issue around the cut off remnants of language we see on the upper and lower edges - what might those words be? What discussion are they part of? Should we make some up?

This might make you wonder whether it is worth a trip to the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch to find out? To look at the source. Or is that a waste of time? Perhaps it is better to keep the mystery, to indulge in fantasy and freewheeling speculation?

There is also an element of humour here, displaying writing mistakes as art when normally they are kept hidden or politely ignored. It seems sadistic (picking on a child) and not say (as was common in exhibitions in the eighties with the rise of theory) scrutinising an adult’s correspondence when looking for psychoanalytical content (parapraxis). The writing (long before fountain pens) looks so spidery, so nervous, so vulnerable.

Pardington’s scale gives these thickly framed linear images clout, but whether they would hold your interest over a long period, I’m not sure. It is possible, because some (the corrected misspellings) have an ugliness that grates, a repulsiveness that you might even get used to and end up loving. Maybe that is a result of our digital era, and that these now look so much from a far distant time. Or they’ve simply become strange configurations without semantic content - gestural pictographs that could ‘work’ (as formal ‘drawings’) just as satisfactorily upside down.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.