John Hurrell – 25 August, 2015

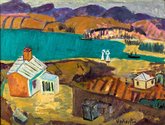

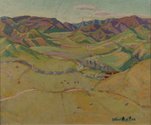

Woollaston, in this country, is unusual because of the rawness of his paint application, and earthy palette; the link between his board or canvas support, its blurry coloured, dry marks and the muddy ground beneath his feet - and his avoidance of anything sweet or ingratiating. There is also his strange sense of compacted and buckled space, the way it scrunched up and tightened the very air and land before him.

Auckland

Toss Woollaston

Woollaston: The Wallace Arts Trust Collection, 1931 - 1996

30 June - 6 September 2015

The name of Toss Woollaston (1910 -1998) - when I was at art school in the early seventies - was often paired with that of the pioneering dealer Peter McLeavey, and also with his great friend Colin McCahon (1919 -1987). The two artists often went on trips to paint and draw landscapes together, and with Rita Angus (1908 -1970), Doris Lusk (1916 -1990), Leo Bensemann (1912- 1986) and others, they represented a variety of Christchurch based, New Zealand avant garde. McCahon and Woollaston, in particular, loved studying geological formations, weather conditions and portraiture. McCahon obviously had a very different sort of sensibility from his friend: he had greater ambition in his range of investigations, was more interested in the use of language or symbolism, and religious /philosophical themes, and admired Woollaston’s interest in atmospheric light.

Woollaston, in this country, is unusual because of the rawness of his paint application, and earthy palette; the link between his board or canvas support, its blurry coloured, dry marks and the muddy ground beneath his feet - and his avoidance of anything sweet or ingratiating. (Most photographs never successfully capture his soft browny hues; their calculated lack of synthetic stringency.) There is also his strange sense of compacted and buckled space, the way it scrunched up and tightened the very air and land before him - as if he had yanked on invisible threads that extended out towards the distant corners of the vista, so that under pressure everything became twisted and compressed. His tactile approach to paint application, the density of painted marks on the board surface where the picture plane is emphasised and far away landscape features advance upon the viewer - its ‘looming’ quality - owes something to the mysticism of Wordsworth’s The Prelude.

Since his death Woollaston hasn’t been seen or discussed much at all, apart from some impressive exhibitions at Te Papa of his panoramas - wide horizontal vistas his brilliant dealer persuaded him to explore. Here in Auckland, this Wallace Arts Trust presentation in the Pah Homestead is a treat because of its comparative rarity, one that provides a chance to think about this artist’s uncompromising and innovative practice.

The front downstairs rooms and corridors of the Pah Homestead display the paintings, and in a large less ‘domesticated’ gallery on the other side of the building, there is a fine assortment of brush and ink drawings, vaguely in the style of Rouault. In the painting rooms, while there are too many on the walls, some absurdly high, we are presented with an exciting opportunity to see a large number of oils, watercolours, pencil and ink drawings together.

In almost all the paintings - apart from a couple of early ones from the thirties - we see Woollaston’s deep love of Cézanne, the tipping up of the picture plane and the tugging (close) and pushing (away) of different clusters of paint marks as air and ‘solid’ matter rub up against each other. The more linear calligraphic ink drawings, occasionally assisted by white paint or pencil, with their quickness of execution and frayed, scratchy edges, have a peculiar looping rhythm and occasional Baconesque hints of deformity, avoiding detail as (in Erua) they describe the shadowy body and head of a schoolboy, made with washy streaks and improvised flicks and sweeps of the brush.

Accompanying the exhibition is a large purchasable, hardcover book, containing illustrations of all the Woollaston works in the Wallace Collection. The images of the black ink drawings are particularly accurate, and while Woollaston’s subtly coloured paintings have always been a minefield for any publisher of his images, the publication is clearly useful. Oliver Stead’s series of texts are packed with contextualising biographical information, and the range of Woollaston’s practice discussed is impressive, but for those interested in grasping the conceptual structures behind the spatial orientation of the work, the most useful guide is probably Tony Green’s beautifully written, admirably concise little VUP publication, Toss Woollaston: Origins & Influence. Like this show, it’s worth seeking out.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.