Julian McKinnon – 9 February, 2016

Van Dyk makes some astute observations about Pick and her practice. “What my subject choice means is initially unconscious, but becomes conscious because people are always asking me what it's about,” says a candid Pick, revealing how an artist's understanding of an artwork can continue to develop after its completion. Van Dyk, looking at overarching themes in image content, asks, “What are the connections between festival goers at Woodstock and today's teenagers who operate in a world of social media?”

White Noise

Catalogue for the Seraphine Pick exhibition curated by Sian van Dyk

Introduction by Courtney Johnson

Essays by Megan Dunn and Sian van Dyk

Photo essay by Birgit Krippner of studio images

Colour reproductions of the 24 exhibited works and installation shots

Hardcover, 117 pp

The Dowse, November, 2015

White Noise is a publication detailing a major exhibition of Seraphine Pick‘s paintings at The Dowse. The titular exhibition took place in 2015 and early 2016, presenting works Pick produced over a five-year period. The resulting book, a lovely object, is hardbound and packed with images of artworks, studio shots, and installation vistas from The Dowse. For painters, these images will excite. Pick‘s studio space is expansive, airy, swarming with paints, artworks, and books, overrun with works in progress and reference material. Essays by Megan Dunn and Sian van Dyk round out the ideational content.

As both essays point out (along with the foreword, written by Courtney Johnston), the work at the heart of this publication marks a departure or transition in Pick‘s career. Reproductions scarcely, if ever, do justice to the artworks they depict; yet these works look terrific in a book format. Produced between 2010 and 2015, these paintings shift away from the psycho-paranoic symbolic dreamscapes of her earlier works, and into territory that is, at a glance, more convivial. Yet the content is far from superficial. The paintings show hippies, wasted youths, clusters of people engaging in group hugs, concerts, and esoteric rituals. The figures range from inebriated, vulnerable, to blissful or contemplative. The paintings are sensitive, confident, and radiant.

Dunn’s essay, Silence or Sound, picks up on a stop-motion animation Pick produced for the opening sequence to Jane Campion’s TV show, Top of the Lake. The animation shows an image of a lake dripping and morphing in to a cascade of paint, from which a stag’s head emerges.

“The watery realm of the lake doubles as the subconscious,” says Dunn, as she identifies a broader resonance between this sequence and the development of Pick’s work. She quotes Pick:

“There’s been a technical shift but also a content shift that I haven’t quite worked out yet. I’ve moved into using found images more and more, rather than making stuff up so much. The focus becomes more about making the painting.”

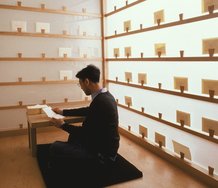

A 2010 painting appears to have been the source of the book and exhibition title. White Noise, oil on linen, depicts Roky Erikson, a psychedelic rock pioneer, accompanied by a white horse. Erikson, a schizophrenic, was in and out of mental institutions in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Apparently after returning home from institutional care, he would turn on various appliances to create white noise, in an attempt to block out all of his mental buzzing. “And that’s what all of these people are doing, they’re blocking out the noise,” Dunn quotes Pick as saying. In an age of ever-increasing stimulus and time starvation, such evasion of the incessant noise of our stressed out society, be it through inebriation, meditation or whatever else, is an understandable phenomenon.

Sian van Dyk’s essay, Everything Old is New Again, explores Pick’s painting against the backdrop of the 21st Century’s proliferation of digital culture. Pick’s sourcing of imagery from search engines, along with her observance from a distance, of social media, leads van Dyk into an elaborate discussion of the internet. Whilst an interesting dimension to the artwork, this method of sourcing and image generation is perhaps more heavily weighted in this text than an analysis of the paintings themselves.

Nevertheless van Dyk makes some astute observations about Pick and her practice. “What my subject choice means is initially unconscious, but becomes conscious because people are always asking me what it’s about,” says a candid Pick, revealing how an artist’s understanding of an artwork can continue to develop after its completion. Van Dyk, looking at overarching themes in image content, asks, “What are the connections between festival goers at Woodstock and today’s teenagers who operate in a world of social media? Are they searching for the same things?” It may be that the utopia an earlier generation sought in counterculture and psychedelics, today’s youth looks for in the ever-shifting sands of technology development and internet memes.

Perhaps Instagram can serve up what free love couldn’t, or perhaps there is a quiet unease at the essence of the human condition that will always lead us to grasp for something out of reach. Whatever the case, White Noise will offer a few moments respite from a continually-unsatisfactory world, and won’t require a gadget or network to do so. Glorious imagery and some thought provoking written content make this a worthwhile addition to your book collection, particularly if you’re a fan of Pick.

Julian McKinnon

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.