Julian McKinnon – 13 December, 2016

One day my teacher said: “Mingwei I want you to come to this space. We knelt and he placed an apple on the mat in front of me. He said “I will give you an hour to tell me exactly what this is.” So I said, “it's an apple. It's green, and a little bit red,” and so on. After about 30 seconds I ran out of verbal description. What came next was the longest and most awkward 59 and a half minutes of my life. At the end of the hour he said, “Taste it.” So I bit into it and the sensation was indescribable. Then I really knew what an apple was.” For Mingwei those formative experiences feed into his work to this day.

.

Photos cluster the wall. Faded sepia portraits showing individuals and groups of people jostle for attention in restrained light. They’re aged and intimate. Grandfather with his friends visiting Tokyo, 1928 (second from right in the back row) is the title of a photo showing a group of young men. A portrait of a wide-eyed child reads Lee Mingwei’s mother as a child wearing a Japanese Kimono. As the images progress through to colours and clothing styles that indicate the 1970s, the exhibiting artist himself appears, as a child and then as a teenager. All of these images are of Lee Mingwei or his family. The title of the exhibition Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation is both a play on the term ‘relational art’ (or relational aesthetics), as well as a literal description of some of the content.

“The show itself starts with my own family lineage, rather than anything else. So you come to the exhibition and the first thing you see is a picture of my great-grandparents. Then it follows through all the way through to a picture of myself when I was about 14,” says Mingwei - a softly spoken and highly articulate man of youthful appearance. I talk with him of the significance to Maori of whakapapa, and the interesting relationship that has to his work. “On my mothers side of the family I am part Taiwanese aboriginal (the majority of the population of Taiwan is Han Chinese), from a tribe called P’in Pu. The tribe is matriarchal, and so we always very close to the maternal side of the family. When I arrived in New Zealand, there was something very familiar about Maori culture and aesthetic, though I couldn’t quite pin it down. Linguistically there is a link between Maori (and other Pacific languages) and Taiwanese aboriginal language, and there are genetic links too. Maybe that’s part of what I feel. A cultural and linguistic relationship.”

It’s not just Minwei’s family lineage that features in the exhibition, his artistic genealogy is also on display. Works by Lee Ufan, Yves Klein, John Cage, and Allan Kaprow (amongst others) foreground, augment and give context to this concise but excellent survey of Lee Mingwei’s work to date. “When I was an undergraduate at the California College of the Arts, my professor was Suzanne Lacey, who is an iconic social practitioner. She is also perhaps one of the best-known students of Allan Kaprow, who in turn learnt from John Cage. Lineage is very important in East-Asian culture, so I’m very happy to be able to have that as part of the discussion in a survey show like this,” he says.

When asked about what led him to artistic practice in the first place, Mingwei offered an intriguing back-story. “When I was growing up in Taiwan, every summer my parents would send me to a monastery. This happened for six years from the time I was five. I had a natural affiliation with spiritual places - temples, mosques, chapels, and my father knew a great Zen master. So it was arranged for me to spend between a month and a month and a half every summer with my teacher up in the monastery. It was a very simple life. There was no electricity. We would wake up at four in the morning and meditate, then clean the temple. I learnt about silence and paying attention to everything I did. One very strong memory is from the first year I went there. I was a very chatty child, a city kid who watched American sitcoms. I went there and there was no T.V. and we would go to bed when the sun set.

One day my teacher said: “Mingwei I want you to come to this space. It was a tatami space. We knelt and he placed an apple on the mat in front of me. He said “I will give you an hour to tell me exactly what this is.” Then he rang a bell. So I said, “it’s an apple. It’s green, and a little bit red,” and so on. After about 30 seconds I ran out of verbal description. What came next was the longest and most awkward 59 and a half minutes of my life. There are no words for that moment. At the end of the hour he rang his bell and said, “Taste it.” So I bit into it and the sensation was indescribable. Then I really knew what an apple was. For a five-year-old kid that was really a memory that burned into my psyche and personality.” For Mingwei those formative experiences feed into his work to this day. “There is something about simplicity, or simple gestures, though loaded with complex memory, sensation, and ritual, that is present throughout my practice,” he says.

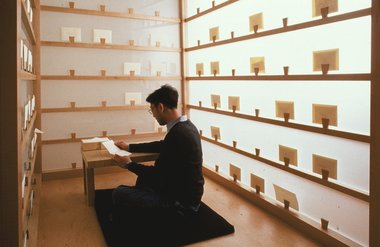

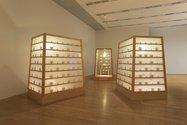

One of the works on display, The Letter Writing Project, encapsulates this summary of Mingwei’s practice. Three simple, booth-like wooden structures are equipped with desks and writing stationary. The arrangement in each is slightly different, with space created for standing, sitting, and kneeling respectively - three different postures for meditation according to Mingwei. Participants are invited to put to paper their feelings, and write something concerning forgiveness or gratitude. Once written the letter can be sealed and addressed - in which case the gallery will send it to the addressee - or left unaddressed, unsealed, to be read by gallery visitors to whom the author is anonymous. The intention of this project is to release unresolved tensions or feelings in a safe space, as an artistic ritual.

Transformation and personal encounter are recurrent themes in Mingwei’s work. The Sleeping Project occupies another of Auckland Art Gallery’s spaces, looking out onto Albert Park. Two single wooden beds are placed around two metres apart, and desks with attached lamps surround the walls. Participants can leave their details on a card in the space. Cards are then drawn to determine which participants are offered the opportunity to spend the night sleeping in the gallery, accompanied by either the artist or a staff member. The intention is to create a space for a personal encounter between two strangers. Mingwei recounted how this work came about, during a long distance train journey shared with a stranger, who told him his personal experience of surviving the holocaust as a Polish Jew.

Without intending to, I responded with a story about my own grandfather - an unusual departure from the format of interviews in which the artist is subject. My grandfather spent three years as a prisoner of war in Germany during WW2; his tale of grueling hardship and against the odds survival seemed to naturally segue into the conversation; its telling to someone I barely knew seemed to decant some aspect of it, to release some part of its intergenerational pain. This is at the essence of what Mingwei does with his work - bringing the viewer’s experiences in to the discussion. “That train journey brought about a deeply meaningful encounter between me and that gentleman. We were strangers, and yet that experience was in some small way transformative for us both. Our society gives a privilege to the artist, to transform. I think everyone has the ability to do that, though society doesn’t see it as the role of someone who for example is working in I.T. to make some sort of transformative action.”

Reading through Mingwei’s artistic history one work in particular caught my attention (although it is not on show at Auckland Art Gallery) Guernica in Sand. “All of us know Picasso’s Guernica, and most of us are also familiar with the sand mandela - with its connotations of creation and destruction intertwined,” says Mingwei of the work’s origins. It was a cluster of related situations and experiences that led him to the work itself. “I was exhibiting in Chicago, and had a really huge space to work with. I thought ‘I want to do something really big, and really make use of this space.’ Not long before that I had been travelling in Bolivia and got trapped in a sandstorm. The sand started to pile up, and cover the jeep I was in. This is really quite dangerous, as if you get covered you just disappear and no one can find you. Fortunately the storm stopped and we were able to get out. I thought to myself then that I wanted to do something with sand as a material - to speak about destruction and creation, as a cycle. Then I saw the original Guernica in Madrid - a painted inspired by horrendous destruction that became a tremendously celebrated work of art. Those three aspects came together and I decided that I wanted to make a sand painting based on Guernica.

But that was just the beginning of this project. It’s not just purely a sand painting - That alone would have no spirit to it, no tension. It would just be static. So the project has three phases to it. One is when it’s not disturbed. The second is when I’m creating the last stage of the work and someone else starts walking on to it. There’s a tension between someone who’s creating something and another person who is creating something else. I tend not to use the word ‘destroying’ because the person who’s walking on the painting could also be creating something - it depends on your frame of mind. So after a whole day of that interaction, a third and a fourth person also walk on the work. And the transformation really takes shape. Then the concluding phase happens, when all four performers take a broom and sweep the sand, and then the work is no longer interactive. With that project I’m looking at the idea of cycles and impermanence - which is definitely related to the idea of the sand mandela - where this thing is created in painstaking detail. Then, with a gesture, it’s gone. I had a very interesting conversation with a Zen master who said about that project that after the sand has been swept, Picasso’s Guernica still exists within the sand, though our karma or time of seeing it is gone. It’s no longer ‘visible’, but it’s still there.”

Mingwei talks openly about the economic conditions in which his work has been able to prosper. “These works are similar to a canary that needs a golden cage, which is the physical structure and framework of the museum to protect it, otherwise it would be eaten by a hawk. Within that framework it can sing a beautiful song, though it wouldn’t survive very long in the wild. I’m very happy with that because it’s the nature of my work. One of the reasons I’m able to create these projects that are not commercial is that there are museums and institutions that are willing to commission work that doesn’t have an obvious commercial component to it. My work is more about ideas and aesthetic. Someone said that a museum is a safe place for an unsafe idea. The museum provides a very fertile ground to have a philosophical discourse, which would be very difficult to have in an environment, such as a dealer gallery, where there needs to be a commercial price tag attached to it.”

Mingwei has lived in New York for many years, though he is currently based in Paris. His living situation has presented a number of opportunities for him going forward. He has a number of soon-to-be-announced exhibitions lined up for major European institutions in 2017, which would mark a feather in the cap for any artist in the world. Though he remains humble. “Most of my projects have been in the USA and Asia Pacific, so it’s good to have an opportunity to show more in Europe,” he says.

Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation is on show at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki until Sunday 19th March 2017. There is a door charge of $12.50. Concessions $10.00.

Julian McKinnon

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.