John Hurrell – 12 December, 2016

What is particularly fascinating about this international craze for slide acquisition was the importance of Oamaru with its rare access to diatomite, a type of geological deposit 35 million years old packed with a vast variety of microscopic silica skeletons from various undersea organisms.

Wayne Barrar: The Glass Archive

Photographs by Wayne Barrar

Essays by Kelley Wilder and Wayne Barrar,

Book design by Anna Brown

Softcover, colour illustrations, 49 pp.

Publication accompanying the exhibition From an Ancient Sea: Oamaru and the Glass Archive held at the Forrester Gallery, Oamaru (9 July - 4 September 2016).

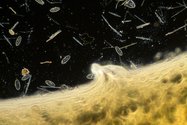

Diatoms are a variety of algae that although unicellular, form colonies that often join up to form ribbons, fans or stars. Microscopic plankton that dwell in water they are transparent, having delicate, symmetrical, patterned and perforated exoskeletons made of silica. When fresh (not stored in formalin), and placed on slides, backlit and photographed, they take on a beautiful jewellike quality. Formally arranged and digitally documented they make stunning crystalline compositions.

These ubiquitous but engrossing plant forms, preserved in slides - as when photographed by Wayne Barrar - collectively make a visually thrilling little book. Not only are its highly intricate images astonishing but it is highly informative with erudite essays that elaborate on the context of the various slide archives of recent or fossilised source material from around the world that Barrar has utilised.

Two contributing texts from Kelley Wilder and the artist discuss the Victorian mania for diatom slide collecting (a network for buying and selling) that was concurrent with the nineteenth century interest in optics and the development of instruments like the microscope, stereoscope and camera. What is particularly fascinating about this international craze for slide acquisition was the importance of Oamaru with its rare access to diatomite, a type of geological deposit 35 million years old packed with a vast variety of microscopic silica skeletons from these various undersea organisms.

Other sources of diatoms and microscopic sponges included guano stripped from tropical islands for fertiliser and residue extracted from underground railway tunnelling or the digging of artesian wells, but the Oamaru deposits (found only on some small inland farms) were regarded as exceptional because of their diversity of species, many of which are now extinct.

With this collegial collecting community, information was circulated surprisingly quickly, and science fairs like The Great Exhibition (London, 1851) aided the process, as did emerging publications like Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Oxford Dictionary.

As sort after commodities some diatom slides attracted huge prices, the discovery and accumulation of specimens being linked to the global expansion of colonialism, the burgeoning accumulation of scientific knowledge and opening up of trade routes. Photography historian Kelley Wilder points out that as the nineteenth century gave way to that of the twentieth, so did the principles structuring the organisation of specimen groups on these slides change. They moved from random scatterings of specimens (‘strews’) to kaleidoscopic arrays that were dense in the centre and thinner in the edges, and then towards parallel rows of specimens that reflected evolving taxonomies with hierarchies.

Designed by Anna Brown this stunning little publication features blue type and Kleinian blue endpapers. With the hovering forms in Barrar’s images looking like gems or types of snowflake the book is surprisingly sumptuous. A wonderful read, it is a fascinating addition to his other achievements like An Expanding Subterra.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.