Julian McKinnon – 16 June, 2018

For those who see the closure as unconscionable (and I am among their number), the question as to the best course of action looms large. Appeals to the Prime Minister (in her capacity as Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage), and the Minister of Education have been made by various concerned members of the community. They may yet have some say on the eventual outcome. When the review process is finalised, and an announcement on the fate of the libraries made, chances are high that there is going to be cause for plenty more protest and appeal for reprieve, and it will be a matter of necessity that all hands are resolutely on deck.

EyeContact Essay #24

Author’s note: All three of the Creative Arts and Industries libraries are under threat and worth saving. This article speaks in general terms about all three, though its specific focus is the Fine Arts Library.

The University of Auckland recently released a review document that proposed the closure of several specialist libraries, and the amalgamation of their resources into its General Library. The affected libraries are Fine Arts, Architecture and Planning, and Music and Dance—all three from the Faculty of Creative Arts and Industries (CAI). The proposal has triggered the strongest protest response from students and the broader arts community in recent memory.

Actions so far have included a large-scale protest outside the university’s General Library on the 30th of April, a library occupation ‘learn in’ at the Fine Arts Library, and at the graduation ceremony on the 11th of May a significant number of graduating students refused to shake the hand of Vice-Chancellor Stuart McCutcheon, who is seen by many as the principal architect of the planned closures. Another large-scale protest was held at the university on the 17th of May. In more recent weeks, active demonstrations have quietened.

The university’s CAI Library Review report, which makes the case for the closures, states that the libraries are no longer fit for purpose. Built in the 70s and 80s, they lack digital resources and disabled access. Further development of the General Library into a ‘wananga for learning and research across disciplines’ is outlined as a one size fits all solution to the university’s library requirements (ironically the report also states that the strategic direction will see fewer generic or one size fits all solutions). It further states that refurbishment of the three CAI libraries wouldn’t be cost effective or pragmatic on account of dwindling usage.

According to the review, usage of the CAI libraries is somewhat at odds to the broader trend across the university. In total, library lending at the university declined 43% between 2012 and 2016. For CAI libraries in the same period, the decline in usage was 4%. Similarly, it makes the case that university research processes are shifting to electronic resources, yet states that this is not the case in Creative Arts and Industries where physical documents are preferred. These observations seem to suggest a set of specialist usage and needs, yet the proposal makes the case for amalgamation regardless.

This seeming internal contradiction is picked up in a letter sent to VC McCutcheon by Art Association of Australia and New Zealand President, Dr Anthony White: “[…] the information used to justify the proposed change in the Libraries Review is contradictory and presents a case for maintaining and improving the library rather than closing it. […] The importance of the library to the continued vitality of the University of Auckland means that there simply is no clear, defensible justification for the decision. The only conclusion one can reach is that the library has been unjustly targeted due to a misperception or misunderstanding of its significance.”

In another letter, art writer, curator and former public gallery director Priscilla Pitts made the comment, “The university’s report […] far from being objective, open-minded and exploratory, appears to have been written solely to support a decision that has already been taken, seemingly on pure financial grounds.” Approached for further comment for this article, she added: “A number of matters that were acknowledged as issues or negatives in the body of the report were simply not taken into consideration in the final recommendations […]. Some of the reasons for closure seemed dubious. One of those was the apparent lack of disabled access. I don’t know about the other specialist libraries but there is disabled access to the majority of the Elam library and there are always staff ready and willing to assist with material that’s held in the one small upstairs area.”

Pitts also made further comment on the review process, “As far as I could tell, no submissions had been invited from affected parties; certainly none were recorded. I’ve been a member of three university review panels, reviewing specific programmes and facilities. In all those cases submissions were invited from staff, students and other interested parties both within and outside the university. In all cases several submissions were received, either in person or in writing and all were considered when making recommendations.”

In an opinion piece in the New Zealand Herald on the 30th of April, Professor McCutcheon states that the university is driven by budgetary considerations, and reducing operating costs is preferable to reducing numbers of academic staff. He acknowledges that library materials used less often are stored off campus, but are available at 24 hours’ notice. He also claims that access for CAI students will be enhanced on account of the longer opening hours of the general library when compared to the specialist libraries.

According to gallerist, AUT visual arts lecturer, and Elam graduate Anna Miles this claim is spurious. “How in practice can access to these collections be improved when the Main Library is already at 80% capacity? Much of the material will be shelved off site which means it is accessible in theory only. It’s important to understand the ways creative students research. […] Catalogues and databases are not the initial ways they clarify their interests - rather they enlarge their visual literacy by browsing. The serendipity that access to real collections represents is extremely important to the way they learn. Most visual arts students can only assess if a book is important to them by picking it up, if they have to wait 24 hours to do so, few will,” she said. In further comment she added, “The University is acting as a reckless steward of material that has taken decades to assemble. If this plan is enacted irrevocable damage will be done to the wider, ongoing cultural life of our society.”

White, Pitts, and Miles are far from alone in their scepticism. A wide range of members of the visual arts community have voiced concern at the proposed closure, with letters from distinguished artists, gallerists, curators, museum directors, et cetera pouring in from around New Zealand and abroad (an excellent record of letters to the Vice-Chancellor can be seen here).

Notable comments have included a joint letter from distinguished young alumni and art world luminaries Simon Denny and Luke Willis Thompson. The pair stated that in their experience internationally, they have proudly claimed their education at Elam as equal to that in many of the world’s leading art academies. “We view the Fine Arts Library, as a single dedicated space of research integrated into the studio environment, as essential in the ongoing veracity of that claim,” they said.

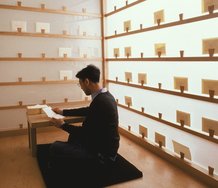

Elam alumnus and current head of graphic design at Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academie, David Bennewith claimed in his letter that the Elam library was integral to his education. He also drew comparison to the library at the Rietveld, which is classified as a workshop. “This makes it as necessary as all the other workshops (metal, wood, typography and painting, textile, glass, etc.) that provide learning and making roles in our students education. […] The situation of the library in our school contributes to the learning, development and community of our school, it would be at a loss without it.”

Acclaimed filmmaker Florian Habicht, another Elam alumnus, provided direct comment for this article, “Who ever decided to close down the Fine Arts Library has no idea what it means to be an artist. They have no idea how special and important this library is. The Elam library needs to be at Elam! I got so much inspiration from the Fine Arts Library. From having all the art books in one place, having them in the environment where we make art, the inspirational feeling & atmosphere, and it is the only place that brings together all the individual Fine Arts students. I wrote many film scripts in the library, and still visit it twenty years later.”

The widespread value placed upon this archive doesn’t appear to be lost on those that prepared the proposal. They cite a sense of loss and the perception of ‘decreased access’ from staff and students among the challenges of implementation. It may be the case that the university administration simply cannot see past its balance sheets, and that economic concerns trump all others. After all, this is simply the latest move in a broader trend within the university towards corporatisation. A significant number of staff and students are opposed to such an approach on ideological grounds, a critique countered by McCutcheon in his Herald article: “The fact that we run a billion-dollar public institution in a business-like manner is not the issue here. Had we failed to do that we would now be at the brink of insolvency, as a number of public tertiary institutions are.”

Rising costs and narrowing budgets are considerations that are hard to ignore, and the current woes of Unitec are a useful case in point. However, in its leadership, the university cannot fall prey to the false principle that fiscal concerns come before all other forms of value. Closure of the Fine Arts library in particular would be a huge loss. It is generally considered the best of its type in Australasia, some say in the Southern Hemisphere, and it has been deeply important to successive generations of artists and researchers. Once its resources have been amalgamated into the general library, it’s highly unlikely to ever be resurrected as a standalone facility. And this is the key issue—once centralised, the specific concerns and value of a Fine Arts collection will be diluted. Some of it will undoubtedly be lost. The library as it stands has been developed over generations, its value to future generations is unmeasurable. It is a unique cultural taonga, and the fight to protect it is imperative.

McCutcheon’s Herald article also states that space freed up from the libraries will be used for student study space. As the School of Fine Arts will lose its post-graduate studio facility (Elam B) at the end of this year, greater demands will be placed on the existing building footprint - an increase in studio space would be a welcome reprieve if it came about by other means. It is stretching credibility beyond breaking point to suggest, as the proposal does, that the closures will enhance the study experience for students. The principle at play here appears to be about maximising enrolments whilst cutting back expenditure, or wringing further profits from fewer resources. This may well serve short term fiscal goals, but the longer-term interests of Elam, and more broadly the university itself, will suffer.

Along with Canterbury’s Ilam, Elam has been the country’s most esteemed art school for more than a century. It holds on to that reputation today. Yet, if the university continues to downgrade its resources and staffing levels, public esteem will eventually reflect that. Disgruntled students have family and friends, and their experiences are passed on to the broader community for years after the university has stopped collecting their fees and associated government funding. The University of Auckland should be proud of Elam’s reputation and continuing sway both here and abroad. It’s something to build upon and safeguard for the future.

When approached for comment on this EyeContact article, on the 6th of June, the Vice-Chancellor stated that he was unable to delve into detail as the consultation process was still underway and the outcome of the proposal was not yet determined. However, he was prepared to comment on the prospect of reputational harm to the institution, “I am not concerned about potential harm to the reputation of Elam […] The creative arts, and the arts in general, are very important to our position as a leading, comprehensive University and we are not about to do anything that would harm them. The reason I’m not concerned is that there is no apparent correlation between the reputation of parts of the University and the question of whether or not they have their own specialist library. For example, the Faculty of Arts does not have its own specialist library and yet its disciplines have some of the highest international rankings of all the disciplines in the University. Similarly, the Engineering Library was consolidated with the General Library several years ago, yet there has been no discernible impact on the reputation of the Engineering School.”

This statement, in as far as it addresses the reputation of Elam, is seemingly at odds with the opinions of many experts who define this country’s visual arts culture. In her letter to the Vice-Chancellor dated 26th April, Christchurch Art Gallery Senior Curator Dr Lara Strongman articulates a perspective entirely contrary: “I recognise Elam School of Fine Arts as the premier tertiary art school in the country. I believe that the calibre of its teaching staff and the quality of its scholarship, critically supported by its specialist library, are its primary drawcards for prospective students. Removing its library is a bad signal for the brand and scholarly reputation of the School of Fine Arts.” A similar sentiment is expressed in a letter, dated 27th April, authored by Auckland Art Gallery Curator of Contemporary Art Natasha Conland, and co-signed by more than a dozen of her colleagues: “It is hard to imagine how the University of Auckland can uphold its position internationally in relation to scholarship and research in the creative arts, including its circle of alumni and patrons, without this flagship institution.”

As the Vice-Chancellor states, the proposal is not yet a done deal. Though his comments suggest he is unlikely to feel any trepidation about enacting the closures, despite the public outcry to date. For those who see the closure as unconscionable (and I am among their number), the question as to the best course of action looms large. Appeals to the Prime Minister (in her capacity as Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage), and the Minister of Education have been made by various concerned members of the community. They may yet have some say on the eventual outcome. When the review process is finalised, and an announcement on the fate of the libraries made, chances are high that there is going to be cause for plenty more protest and appeal for reprieve, and it will be a matter of necessity that all hands are resolutely on deck.

Intriguingly, the CAI libraries review included an alternative proposal to closure. At least one member of the review panel disagreed with the recommended outcome, and suggested a CAI library be established in an extensive building redevelopment, already planned for a site on Symonds Street. This would see the collections of the CAI libraries housed together, separate from the General Library. Whilst less than ideal, this is perhaps the best remaining hope for saving the Fine Arts Library.

Julian McKinnon

Elam MFA graduate and PhD Candidate

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.