Scott Hamilton – 4 June, 2016

In the decade since Nuku'alofa burned and Tevita Latu was beaten Tonga has changed. A new constitution has restricted the powers of the monarchy and the nobility, and let commoners elect two-thirds of parliament. In the aftermath of the riot pro-democracy leader ‘Akilisi Pohiva was arrested and charged with sedition, but today he is Prime Minister. And yet Tongan democracy is fragile.

Nuku’alofa

On the Spot Arts Collective

Tenth Anniversary Celebration

22April 2016

Tanya Edwards

Me’akai, four new ngatu

22 April - 22 May 2016

The white ute came slowly up the road, wallowing in the muddy potholes outside kava shacks and Chinese bargain stores. Two men sat in the front of the vehicle, and seven or eight more clung to its back. The ute stopped for a couple of seconds beside the white walls of the National Baha’i Centre, then stuttered a few metres and turned off the road onto a lawn.

The driver switched off his engine and sat silently. The man beside him in the passenger seat lit a cigarette. The men on the back of the vehicle stood up, stretched with exaggerated slowness, then squatted again, muttering to one another. Above the ute bats hung from the larger branches of a mango tree. Dusk was an hour away, and the creatures had begun to stir. They squeaked to themselves and shook, and one fell like a piece of rotten fruit onto the lawn.

The men in the ute watched the partygoers, who were spread over the grass around the headquarters of the On the Spot arts collective. Children were dancing with their parents, young men were slapping drums, and staff at On the Spot’s newly opened café were serving drinks and fruit and biscuits.

Eventually Ebonie Fifita-Maka, the creative director of On the Spot, worked her way through the dancers and approached the white ute. The vehicle’s driver rolled down his window and listened expressionlessly as Ebonie said hello, thanked him for coming to the celebrations she had organised for On the Spot’s tenth birthday, and asked how she might be able to help Tonga’s police force. The policeman explained that the people of Nuku’alofa were complaining about the noise that the party was making. The drums were loud; the dancers were loud; the people going in and out of On the Spot’s headquarters were loud. The noise would have to stop; the party would have to stop.

Ebonie had been joined beside the ute by her husband and fellow On the Spot member Steve Maka, and both of them were bewildered. Nuku’alofa is a noisy place. Dogs bark and growl, cars backfire, and stereos and choristers blast their music all through the city’s days and well into its evenings. Were On the Spot’s drummers really any more egregious than the choir rehearsing a few hundred metres away in the Catholic cathedral, or the kids driving their parents’ unmuffled Ford Escort around and around the city’s central district?

Ebonie apologised to the policeman; the policeman nodded slightly and turned his key. As his ute backed out of On the Spot’s property, I noticed that the men squatting on its back were staring past Ebonie and Steve, and past the chastened drummers and dancers, towards a large man drinking at the end of the lawn. Just before the ute turned into the road a young cop gestured towards the end of the yard and laughed shrilly. His fellow passengers laughed with him as the ute lurched away.

The target of the young cops’ stares was Tevita Latu, the most controversial of Tonga’s contemporary artists. During the campaign for democracy that brought Tonga to the verge of revolution a decade ago Latu became famous for the slogans he painted on the walls and pavements of Nuku’alofa. Latu was arrested the day after the riot that gutted downtown Nuku’alofa in 2006, and beaten for a week in a cell somewhere inside Nuku’alofa’s police station. After his release Latu built a shack beside Nuku’alofa’s lagoon and made it the headquarters of the Seleka Club, an organisation dedicated to art, agitation, and kava drinking.

Inside their clubhouse Latu and his comrades invert and subvert the rituals and imagery of traditional Tongan society. They drink kava from a toilet bowl, welcome women and transsexuals to their table, listen to death metal and hip hop rather than sing old kava songs, and paint and draw in a style that owes as much to Basquiat and Braque as to the Tongan past. An On the Spot newsletter being distributed at the party featured an interview with the painter, musician, and long-time Seleka Club member Taniela Potelo. Rejecting the labels ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’, Potelo had told On the Spot that his art was “contentional”.

Tevita Latu, Taniela Potelo and half a dozen other Selekarians had arrived at On the Spot’s party a few minutes before the police.

*

After the uteload of sullen men had disappeared, On the Spot’s drummers went back to work, and dancers rose happily from the grass. I stopped Ebonie Fifita and asked her about the police. “I don’t understand how the noise could have been a problem,” she said. “But we’ve had some trouble with the police before. They park their cars in our driveway, so that we can’t get out and visitors have trouble getting in. We’ve told them not to do it, but they keep doing it.” I wondered whether the police visit was aimed partly at Tevita Latu and his friends. “There’s a history between Tevita and some policemen,” Ebonie said. “I don’t know what, if anything, that means now.”

Tevita Latu was only one of hundreds of Tongans detained after the riot. In 2007 the lawyer and human rights activist Betty Blake published a report about the treatment of these detainees. Working with a ‘community para-legal taskforce’ that included some of Tonga’s top academics, Blake documented the misery of detainees forced into tiny and filthy cells, handcuffed for days on end, and beaten with fists and boots and sticks. Australian and New Zealand cops sent to help Tongan ‘restore security’ after the riot had stood by while their colleagues worked. A fifth of all the detainees had been children.

Blake’s report was studded with photographs of torture victims. With their eyes blacked out for security reasons, a series of young men showed off their stained T shirts, bloated eyes and lips, and pitted scalps. The report was soon uploaded to the internet, and Nuku’alofa’s police were enraged when they discovered Tevita Latu’s battered body amongst its illustrations.

Soon Ebonie Fifita-Maka had turned away from me, toward a couple of men wearing matching floral shirts and expensive shoes, and holding what looked like a sandwich board. The men in the floral shirts had been watching Ebonie’s chat to the police with bemused smiles, and now they had something to tell her. Ebonie leaned over the sandwich board to hug both men at once, then turned and stepped after them toward the outdoor deck of On the Spot’s gallery, where a microphone stand had appeared. Partygoers gathered around the improvised stage, a drum roll sounded, and Ebonie held the board above her head. It was a giant cheque from the Bank of the South Pacific, entitling On the Spot to fifteen thousand pa’anga (about ten thousand New Zealand dollars). As Ebonie explained, once the crowd had stopped cheering, Tonga’s leading bank had been impressed by On the Spot’s painters, dancers, musicians, and actors, and admired the group’s commitment to free expression.

As I stood listening to Ebonie’s speech I was joined by a grinning Maikolo Horowitz, an American sociologist and novelist who has taught and researched in Tonga for nearly two decades. “It’s bizarre, isn’t it?” Maikolo said. “One minute the cops want to shut them down, and the next minute bankers are giving them money. Tonga can’t decide what to do with its young artists.”

In the decade since Nuku’alofa burned and Tevita Latu was beaten Tonga has changed. A new constitution has restricted the powers of the monarchy and the nobility, and let commoners elect two-thirds of parliament. In the aftermath of the riot pro-democracy leader ‘Akilisi Pohiva was arrested and charged with sedition, but today he is Prime Minister. And yet Tongan democracy is fragile. In a recent article for Pohiva’s newspaper Ko e Kelea the young journalist ‘Ofa Vetikani complained that Tonga’s elite is still opposed to democracy. Recalcitrant nobles plot a return to power over cocktails, while biased journalists slander the Prime Minister on television and religious conservatives denounce democracy as ungodly.

Maikolo Horowitz had given Vetikani’s polemic to his students. “Every word of it is true,” he told me. “This is a Weimar kingdom. We have democracy, but shadows are forming. What you saw tonight from the police should not be surprising.”

I stepped into On the Spot’s gallery space, which occupies two rooms in the old cottage the group has restored and made its den. In between a set of new ngatu paintings by Tanya Edwards a series of photo collages documented On the Spot’s first ten years. There were shots of members dancing, singing, teaching, painting, performing plays, partying, and hanging out at the beach.

In a famous essay published in the early 1970s, Wystan Curnow argued that because New Zealand was a small society its intellectuals were forced to multitask rather than specialise.(1) Writers often reviewed and edited, and produced poetry as well as prose; painters often had to teach and curate. When Curnow was writing his essay New Zealand had a population of two and a half million; today the Kingdom of Tonga still has only a hundred thousand inhabitants. In such a tiny society intellectuals and artists become dizzyingly versatile. Tonga’s most revered intellectual, the late Futa Helu, was a philosopher, an expert on ancient Greece, a literary critic, an opera singer, an authority on Tongan dance, and a political commentator, amongst other things. Epeli Hau’ofa won an international audience for his short stories and novel, but he was also a poet, an important anthropologist, an expert on Fijian carving, and an academic administrator. On the Spot’s eclecticism is part of a tradition.

Half a dozen women were standing in the middle of a gallery room, with their backs to the ngatu and the photo collages. They were giggling and talking about trousers. I had my exercise book and my pen, because I’d intended making notes about Tanya Edwards’ new paintings; instead, I began to transcribe the conversation I was overhearing.

- I let my daughter wear trousers. I’m not worried.

- I said ‘tuku ‘ia!’ You’re not wearing those! Dr Palu will curse you!

- He is insane. But lots of people like to listen to him. In the diaspora, too…

One of the women turned to me, saw me scribbling, and asked, in what I hoped was a jocular tone, whether I was spying for Dr Ma’afu Palu, the theologian who has lately become Tonga’s most notorious DJ. Palu spends his days at the Free Wesleyan Church’s Siatoutai Theological College, in the countryside outside Nuku’alofa, and some of his evenings behind a microphone at a popular FM station, where he inveighs against secularism, feminism, Prime Minister Pohiva, women who wear trousers, and other threats to the Tongan nation.

When Pohiva announced last year that his government would join the rest of the world in ratifying the United Nations’ Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Palu brought hundreds of people, including Catholic nuns and a former Prime Minister, onto the streets of Nuku’alofa. The crowd chanted slogans like ‘CEDAW 666’ and raised a banner with the legend: A House with Two Masters A House of Doom. In interviews with the media Palu claimed that if Tonga ratified CEDAW the country would return to its pagan past, and Christians would be persecuted. After some of his more cowardly MPs threatened to cross the floor of Tonga’s parliament, Pohiva decided not to sign the UN’s convention.

Palu ends his radio programmes by cursing the people he holds responsible for Tonga’s slide towards democracy and pluralism. ‘Ofa Guttenbeil-Likiliki is the director of Tonga’s Women’s and Children’s Crisis Centre, a supporter of CEDAW, and a regular target of Palu. “He curses me,” she explained, “and once he cursed my children, and said that he hoped I would live to see his curses fulfilled. We were laughing about his fascination with women’s trousers, but Ma’afu Palu is really no joke. He is guilty of hate speech.”

‘Ofa had come to On the Spot’s tenth birthday party because she admired the organisation’s pedagogical work.”They want to shift consciousness, to make debate,” she said. “They perform plays about problems in the family, about families breaking up, and they take these plays to the villages, they discuss the plays with villagers. I wish Ma’afu Palu would watch On the Spot. He condemns me for offering refuges and counselling to battered wives and girlfriends. He says that our crisis centre promotes promiscuity. He tells battered wives to talk to their church minister, to go back to their husbands.”

Like so many religious fundamentalists, Palu seems obsessed with sex. In his self-published chapbook God, the Bible, and Sex, which I had bought for five pa’anga from the Friendly Islands Bookshop, he condemns the combination of a high-speed internet and Western feminism for bringing depraved practices like oral sex to his homeland, and complains that Tongans would nowadays rather watch porn than attend church on Sundays.

*

Ma’afu Palu and other conservatives might be preoccupied with the danger that allegedly exotic ideas like democracy and feminism pose to Tongans, but Tanya Edwards would rather they thought about the perils of exotic food. Forty percent of the kingdom’s adults have either heart disease, diabetes, or stroke-related problems, and most of the afflicted are overweight. Yet mutton flaps and corned beef from New Zealand and fried chicken from Hawa’ii are still distributed like blessings at church feasts and weddings and coronations, and Nuku’alofa has almost as many fast food joints as churches. When her father was diagnosed with diabetes Edwards had begun to paint the cheap imported foods that have made Tongans the unhealthiest people in the world.

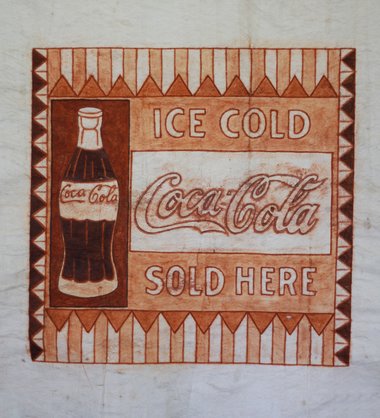

Edwards had made her new images on ngatu, the traditional material of Tongan painters, and used familiar shades of brown and orange. But Edwards’ subject matter contrasted with that of most ngatu painters, who tend to deploy a set of images and motifs with hallowed and solemn meanings - lions to represent the monarchy, crosses and Norfolk pines remembering missionaries, and so on. One of Edwards’ paintings was modelled on a slightly outdated advertisement for coca cola - it showed a glass bottle, and the legend Ice Cold Coca Cola Sold Here - and another featured a bulging can of Palm Corned Beef. A third ngatu showed eight orange-skinned, sharp-finned fish - were they coral trout, or perhaps bass? - arranged vertically, and a fourth featured the fin-like leaves and scaly, complicated skins of two ripe pineapples. Both the pineapples and the fish had been given the caption Fakalahi Me’akai (Other Food). Edwards had framed each of her images with networks of straight lines that seemed to allude to yet not repeat the intricate decorative patterns of traditional ngatu.

“I want to make people think about what they’re putting in their stomachs,” Edwards told me later, when I found her talking with Tevita Latu on the lawn. “I have juxtaposed introduced and indigenous foods. Tongans should rediscover their old diet.” But Edwards’ ngatu are a challenge to popular Tongan aesthetics, as well as to the kingdom’s dominant diet. She is one of a generation of artists who are trying to renovate ngatu painting. “I have studied ngatu, studied the tradition, studied all the symbols,” she told me. “But I don’t always want to paint those symbols. They don’t necessarily speak for me.”

Ngatu is made from the inner bark of the hiapo tree, which women traditionally strip, soak in seawater, beat, dry, and paint with dyes made from local plants. Usually ngatu painters have used kupesi, or stencils, to put patterns and images on their barkcloth, and then added details by hand. Ngatu traditionally lined the roads to royal residences, and kings and queens still walk across the cloth when they attend public funerals and weddings and other important events.

During certain moments in the past, Edwards explained, ngatu had been a very innovative artform. A ngatu in New Zealand’s national museum shows a spitfire with the words Queen Salote written on its fuselage landing daringly on an uneven runway. That barkcloth celebrates the early 1940s, when thousands of Allied troops occupied Tonga, spending exotic currencies, playing jazz and swing on wind-up gramophones, and riding strange machines. Tongans sent their own troops to fight in the Solomon Islands, and made enough money working as cooks and porters for the palangi newcomers to pay for the construction of a couple of spitfires, which Queen Salote presented to Britain’s Royal Air Force. Tanya Edwards admires the artists of the Queen Salote era, who put a new world onto ngatu. In recent decades the desire of tourists for a few familiar motifs and the resistance of some clergymen and nobles have made it more difficult for ngatu painters to innovate.

Just as Andy Warhol’s soup cans upset Americans habituated to the painterly gestures of Abstract Expressionism fifty years ago, so Edwards’ cans and bottles have perturbed Tongans who associate ngatu with picturesque patterns and exalted symbols. Edwards laughed when I asked her whether she identified with Warhol. “I do identify with other Tongans of my generation, people trying to do new things on ngatu,” she said. We discussed Tui Emma Gillies, the Auckland-based artist who has mixed traditional ngatu imagery with precisely painted dreams and memories, and Visesio Siasau, who won last year’s Wallace Award after disfiguring Jesus with a dollar sign and putting him onto barkcloth. “There is no need for Tongans to fear change,” Siasau had told me on a rainy autumn day in Auckland, when he was preparing to fly to New York City to begin the six month residency his Wallace Award had earned. “My ancestors were navigators, and to be a navigator is to accept change, to accept a dynamic state. Innovation is part of Tongan culture.”

*

Near the end of On the Spot’s birthday party I walked back into the group’s den, looking for a shell of kava, and found a group of drummers at work in a small room between the gallery spaces and the café. They squatted in a circle on the floor, shaking Afros and mullets to a quickening beat. On the wall somebody had scribbled a poem in English:

Bring your voice to the rhythm

Let your heart beat in time

The drum of Polynesia

Melanesia harmonise

Melody from Micronesia

Calling out to Unite

In this song

This song of life.

Scott Hamilton

(1). See Wystan Curnow, ‘High Culture in a Small Province,’ in The Critic’s Part: Wystan Curnow Art Writings 1971-2013, edited by C. Barton and R. Leonard, pub. IMA and Adam Art Gallery, 2014, pp 28-47.

Recent Comments

Scott Hamilton

PS: I wasn't able to find this extraordinary and very provocative image in time to include in my essay about ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Scott Hamilton, 1:26 p.m. 21 June, 2016 #

PS: I wasn't able to find this extraordinary and very provocative image in time to include in my essay about Tonga's transgressive ngatu painters, but it has just turned up in all its grotty glory:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2016/06/taniela-petelos-toilet-humour.html

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.