Scott Hamilton – 29 August, 2016

The ‘100% Pure' images are visually and intellectually concise. Many of the scenes they show - a mountain rising into a blue sky, two trampers stepping over boulders in a foaming river - are forthrightly dramatic. Each of their components - each line, each form, each colour - contributes unambiguously to the overall image, and each image is an unambiguous illustration of the slogan ‘100% Pure'. Ambiguity is the enemy of the advertiser.

.

In 1999 Tourism New Zealand solemnly announced that it was ‘rebranding’ this country, and over the last seventeen years our mountains, rivers, forests, beaches, and bays have appeared on billboards beside the ring roads of northern hemisphere cities, in overseas magazines and in newspapers, and at global travel fairs, alongside the slogan ‘100% Pure New Zealand’.

Most of the images used in the ‘100% Pure’ campaign are photographs; a few are paintings modelled on photographs. Whatever their medium, and wherever they appear, the campaign’s images are always glossy, and always carefully edited. Though they depict a range of locations, from New Zealand’s subtropical north to its subantarctic south, and though they feature glimpses of cities as well as rural tableaux, they all communicate one unambiguous message: they say that this country is a spectacular, unpolluted, underpopulated paradise, and therefore the ‘Other’ of the crowded, contaminated societies of the northern hemisphere.

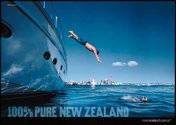

The ‘100% Pure’ campaign often depopulates the landscapes it celebrates. Wrinkles left on hillsides by ancient pa or modern roads are removed digitally; cameras are aimed away from towns and villages, towards empty river valleys or desolate mountains. When signs of human occupation feature in the images of the campaign they are made innocuous, almost irrelevant. A photograph taken in Auckland’s Waitemata harbour, for instance, shows a man and woman diving from a luxury yacht into pure blue water; the Sky Tower rises in the distance. Even near the centre of New Zealand’s largest city, the image assures us, tourists can find places unsullied by New Zealanders.

The ‘100% Pure’ images are visually and intellectually concise. Many of the scenes they show - a mountain rising into a blue sky, two trampers stepping over boulders in a foaming river - are forthrightly dramatic. Each of their components - each line, each form, each colour - contributes unambiguously to the overall image, and each image is an unambiguous illustration of the slogan ‘100% Pure’. Ambiguity is the enemy of the advertiser.

Although the ‘100% Pure’ campaign has been aimed abroad, its images have been reproduced often by New Zealand’s media, and have been internalised by many Kiwis. The slogan ‘100% Pure’ has seemed at times like a mantra, and the images that accompany the slogan like sacred icons.

Those who blaspheme against icons risk public excoriation. In 2011 the environmental scientist Mike Joy wrote an article criticising the increasing pollution of New Zealand’s streams and rivers by runoff from dairy farms. Joy insisted that the slogan ‘100% Pure’ was ‘delusional’, given the state of the nation’s waterways. After he was quoted by the New York Times Joy was condemned for endangering New Zealand’s reputation. Political blogger Cameron Slater accused Joy of ‘economic sabotage’ and said that he ought to be ‘shot at dawn’; an editorial in the New Zealand Herald complained that the scientist’s comments were ‘not appropriate’, and urged him to begin to express himself ‘in a more judicious manner’.

The anxiety of Mike Joy’s critics can be understood. In the twenty-first century New Zealand’s economic strategy has become entwined with the ‘100% Pure’ brand. The tourism industry, which contributes nearly five percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product, uses the brand obsessively, and so do the businesses that send ice cream and yoghurt and bottled water and honey and scores of other products into Asian and European and North American markets.

But the success of the ‘100% Pure’ campaign has had as its byproduct the occlusion of reality. The campaign’s digitally enhanced, carefully edited landscapes have little relation to the real places and spaces of New Zealand. When they internalise the brand, and criticise anyone who dissents from it, New Zealanders risk losing a sense of what their country really looks and feels like.

Emily Jackson’s paintings are everything that the images of the ‘100% Pure’ campaign are not. If the images of the ‘100% Pure’ campaign show a terror of ambiguity, then Jackson’s paintings exult in that quality.

In the 1970s and ‘80s Jackson exhibited regularly in several New Zealand cities, and won praise from a range of reviewers. But her work has been largely unseen since her death in 1993. Now Atuanui Press has published Emily Jackson: a Painter’s Landscape to coincide with an exhibition of Jackson’s paintings at the Inge Doesburg Gallery in Dunedin. Fastidiously edited by Emily’s daughter Bronwen Nicholson, the book includes reproductions of many of Jackson’s paintings and drawings, long excerpts from the journal she kept for much of her working life, letters she sent to family members, reviews and interviews she gained and gave during her years of success, and specially commissioned essays by Gregory O’Brien and Warrick Brown.

Jackson was mentored by Toss Woollaston and Colin McCahon, and shared both of those artists’ fascination with the New Zealand landscape. From her base in the Auckland suburb of Mount Roskill she made forays into New Zealand’s regions, riding gravel roads along ridges and river valleys and counting the peaks of mountain ranges.

Jackson’s journal entries show how often she travelled through the landscapes of rural New Zealand, and how hungrily and carefully she looked at them. But they also reveal her lack of interest in painting what she saw mimetically. She brought a series of cameras along on her journeys, yet never used photographs as a guide when she sat down to paint back in her Mount Eden studio. She never sketched, let alone painted, in the midst of landscapes.

Jackson’s brushwork is fluid, and sometimes florid, so that it can be unclear whether she is painting a mountain or a chunk of cloud, a river or a road, a valley or a ridge. Even when her paintings are relatively clearly rendered, they often feel more like composites than copies. She may show the same mountain from three or four sides, or fuse it with another peak.

In an interview with the journalist Anne Fenwick, Jackson recalled some of the criticism that she had received for ‘flirting with the abstract’. One critic had suggested she stop pushing her painting toward abstraction, but she couldn’t resist. We should be pleased that Jackson couldn’t resist, because her paintings are better for the ambiguity that the push towards abstraction gave to them.

In the pleasant but unremarkable 1984 work Tairua Jackson renders the hills that rise near that Coromandel town reasonably realistically, and gives them naturalistic greens. The sky above and behind her hills is overcast, neutral. In The Torrent, which was painted in the same year, Jackson uses swathes of purple and silver to both obscure and energise the same landscape. Hills suddenly seethe and shake; the sky’s bright light might be about to set fire to the land. Tairua has become both more vivid and more mysterious.

The ambiguity of Jackson’s paintings is not the result of sloppiness, or mischievousness, or indecision. It is a token of her humility in the face of the complexity and otherness of the landscapes she confronts. Again and again in her journals and letters Jackson records the awe that she feels as she travels New Zealand. The scoured and scrubby hills of the King Country; the golden valleys of midsummer Otago, half-deserts and half-oases; the plains of the Manawatu, where the straight lines of fences and roads wait for floodwaters and stray herds of cattle: all encouraged what Noel Bierre calls, in a review, an ‘almost spiritual’ response from the painter.

Jackson is aware of the fluidity as well as the majesty of the landscapes she visits and paints - of the ways that an earthquake or a housing development or the mere movement of a cloud might change the way a place looks and feels. In a letter written the year she painted Tairua and The Torrent, Jackson explained that her first impressions of the Coromandel were changing, as she recreated the region in her mind and in her studio. The dark and ‘rugged’ peaks of the region were becoming ‘something lighter’, something ‘more vibrant’.

The ambiguity in Jackson’s paintings is an acknowledgement of the provisionality and ultimate unknowability of the New Zealand landscape. The ancient Greeks believed that the clouds around Mount Olympus honoured the gods who dwelt there by preserving their mystery. The blurred outlines and wild colours and composite views in Jackson’s paintings honour the mystery of New Zealand.

In one of his rare pieces of art criticism, Martin Heidegger described the link between visual ambiguity and truthfulness. Heidegger was writing about Paul Cezanne, but his remarks might be used to explain Emily Jackson’s achievement.

Heidegger insisted that Cezanne’s repeated and increasingly abstract portraits of Mount Saint-Victoire, a three thousand foot high peak in Provence, were important contributions to philosophy. Few philosophers, Heidegger said, could think as profoundly as Cezanne painted his favourite mountain. Heidegger believed that Cezanne’s paintings of Mounte-Victoire could remind humans of the difference between the ‘world’ - the familiar reality, complete with its categories and conventions, that they navigate every day - and ‘earth’, the primordial reality that lies beneath and behind the ‘world’.

Humans have, Heidegger claimed, a tendency to forget about the primordial reality beyond their quotidian lives, and therefore to forget that their ‘world’ is only one of many possible realities, constructed for them by their language and their culture and their beliefs. In his essay ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, Heidegger tried to understand the relationship between ‘world’ and ‘earth’:

The earth cannot dispense with the Open of the world…The world, again, cannot soar out of the earth’s sight…The earth appears openly cleared as itself only when it is perceived and preserved as that which is by nature undisclosable, that which shrinks from every disclosure and constantly keeps itself closed up.

Elsewhere in the same essay, Heidegger argued that the temples of ancient Greece allowed ‘earth’ to disclose itself through the materials of ‘world’:

The temple-work, in setting up a world, does not cause the material to disappear, but rather causes it to come forth for the very first time and to come into the Open of the work’s world. The rock comes to bear and rest and so first becomes rock; metals come to glimmer and shimmer, colors to glow…

Like the sculptors and architects of ancient Greece, Cezanne allows us a glimpse of ‘earth’. By showing Mount Sainte-Victoire emerging from a mysterious grid of abstract colours and lines, the painter reminded Heidegger of the provisional nature of what was considered reality, and provoked a sort of eerie ecstasy in the philosopher.

Emily Jackson’s landscape paintings can stir the same sort of response in her viewers. By pushing New Zealand’s landscapes to the brink of abstraction, she reminds us of the limitations inherent in our attempts to categorise and define those landscapes. To look carefully at her paintings is to see the ‘world’ of New Zealand emerging from a fertile and mysterious ‘earth’.

When I looked at Cardrona, 1986 for the first time I saw forms and colours, rather than a landscape. Swirling yellow, almost golden paint dominates the work, but a rough triangle of blue appears in its upper left-hand corner. I noticed the contrast between primary colours, and the way Jackson complicates her mass of yellow with smudges of pink and brown and black, so that the colour seems to surge and recede.

But then I saw the painting’s title, and remembered that Cardrona is a valley in central Otago. I recalled how drought and flowering gorse and ragwort can turn the bare grassy hillsides of that region brilliant shades of yellow. I decided that the blue in the painting’s corner had the mixture of depth and brightness common to the skies of the South Island high country in high summer.

Looking closer at that painting, and at the dark smudges that mar and enhance Jackson’s mass of yellow, I imagined dry kanuka waiting for a fire and the brittle, crap-crusted pathways of sheep. One black blotch became, for a moment, the derelict shack of a long-dead goldpanning swagger.

By leaving her landscapes vague and incomplete, Jackson makes them uncommonly vivid for viewers. We add our own details to her scenes, as we bring them back from the edge of abstraction into a world and a history we recognise. In a 1988 journal entry Jackson explained that, for her, painting was ‘the means of transportation into…another level of living’, and talked about the ‘supreme fulfilment’ of bringing ‘something’ out of ‘nothing’.

If the images of the ‘100% Pure’ campaign seek to drain our landscapes of ambiguity and difficulty and turn them into a brand, then the paintings of Emily Jackson give our places and spaces back their mystery and their possibility. They have become, in this era of branded landscapes, urgent and subversive works.

Scott Hamilton

Recent Comments

Richard Taylor

Scott. I read the whole book referred to here. At first, before going tot the launch I thought this was ...

Richard Taylor

But Heidegger, fascinating philosopher though he was, joined the Nazi Party during the war, and mad e sure that the ...

Richard Taylor

At the Glenn Innes Pack in Save I saw someone stacking some orange juice that was "100% Pure", I asked ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 5 comments.

Comment

Richard Taylor, 12:44 p.m. 21 September, 2016 #

A remarkably good review Scott. The question of purity is "attacked" or at least put into question by Derrida in his questioning or deconstruction of Plato and other claims for pure origins, or some overarching perfection. As by implication via Plato's concept of Ideal Forms. Penelope Deutscher shows how the idea say of the Pharmikon (a damaging - or not - medicine or additive) is critiqued by implication as, as you say here, these things are never one state, they are complex, ambiguous. And yet Derrida and others promulgate the same theory that argues for say non object art.

(A point to be interjected here is that that very ambiguity and mystery is not only inherent in all great art but also, in a different modality say, in the art of say Woolaston or Jackson, or in fact in conceptual or "post-object" art, say.)

In general your art critic is right. Landscape etc is, generally passed. But Heidegger (who was inspired by Husserl) inspired Sartre and the French post modernist theorists. Art is radically different. If you add McCahon and say Dick Frizzel to the mix, we have a direct critique.

So the dispute about art and style continues.

For me, art can take any direction: the abstract art of the 50s etc was vital to the development of other art. Art in general cant stand still, so landscape art starts to look like all the other landscape art before it.

Richard Taylor, 12:44 p.m. 21 September, 2016 #

But what about other artists? Are they tackling this purity issue. By implication your critic should be "on your side" on that aspect: it is clearly mostly nonsense, this "pure, green clean NZ". It is propaganda and in fact it is probably healthier in NZ to live in Auckland than any other place: witness the aquifers polluted by cattle manure etc from our farms (and a similar water disaster that lead to long term illnesses and deaths in Canada where the water was untreated with chlorine - and I am very thankful for Sir Dove Myer Robinson for getting the sewerage systems set up in Auckland AND for the engineers who kept me alive with chlorinated water). New Zealand is very polluted, the fertilizers used on land has permeated into rivers, the gorse you mention is a real problem, every where there is erosion since the early settler destroyed the original landscape (Maori had also begun to kill off birds and damage the land but to a lesser extent both due to customs and smaller numbers).

Richard Taylor, 12:46 p.m. 21 September, 2016 #

At the Glenn Innes Pack in Save I saw someone stacking some orange juice that was "100% Pure", I asked him how he could guarantee such a purity, as such "purity" is a myth: there probably has never been any water "uncontaminated" by minerals or even bio organisms that could, in varying degrees, be harmful to humans: in fact it is that very fact that probably helped humans and other animals etc to develop resistance to the other things, that far from being pure and beautiful and benign are also potentially "out to get us", or can be harmful. The same idea of purity is allied to fascist and other ideas of perfection and "progress" (another myth in my view). The man stacking was the owner of the company that made the orange juice: he disagreed, but I kept to my point: he had no answer, but obviously it is better probably to drink such than too much coca-cola (although some coca-cola is probably harmless if taken in small doses). But his "100% Pure Slogan" is like the travel peoples' nonsensical propaganda for this mythical clean green, and as you say unambiguous New Zealand, or Aotearoa.

Richard Taylor, 12:46 p.m. 21 September, 2016 #

But Heidegger, fascinating philosopher though he was, joined the Nazi Party during the war, and mad e sure that the Jewish Husserl (to whom he owed a lot) was sacked (he didn't live long enough to be killed by the Nazis), and Heidegger also extolled the blood of the soil and the folk, and was opposed to what he called techne. Of course his joining the Nazi Party (for which action he never apologized) might have been a sensible move as it was hard to survive in those times. And his interest in art and poetry (he like Holderlin, van Gogh, Rilke, Trakl - although I forget which ones were supported by Wittgenstein - but certainly he was keen on some of those artists and poets). So it is interesting to see his view also of Cezanne. Cezanne is better known for his distortion of perspective and as a forerunner to cubism. But it is a good point about Cezanne's famous mountain.

The Whale Oil bloke sounds a bit unhinged. It is a pity they cant look at the report and try some honesty. If it is true it is true. Now what do we do about whatever destruction of the forests (millions of acres), erosion, contamination by humans everywhere and fertilizers used to excess or unwisely and other things: then we can address the problem.

But I cant see that this is quite what Emily Jackson is about: I suspect these may concern her, but her art is her art.

But in general, the "critic" (and I suspect I know who the critic is), was right. Art is not propaganda and landscape art is, by and large, out the window: but Art it is a human activity that will probably continue in all its permutations of modes, even as we are all entering the coming destruction and chaos (if there is to be any such pessimistic outcome, it, all our concerns, may be "storms in teacups").But if it does go that way, we can all kiss ourselves good bye, but the art will probably go on! After all the mountains are indifferent to our fate.

Richard Taylor, 10:47 p.m. 21 October, 2016 #

Scott. I read the whole book referred to here. At first, before going tot the launch I thought this was about a young artist. It was a good launch...I actually got the book from the library and it is very good. I was intrigued by the combination of the journal, Emily Jackson's struggle to paint (arthritis, some depression, doubts). The book has a n essay by the poet O'Brien, and one by Warwick Brown who analyses her more 'abstract' works and he diaries & letters record her progress as an artist.

She was supported by McCahon and others, and Toss Woolasten who she was at school with. Her 'ambiguity' is for sure. The landscape becomes another world. There are no figures. No purity. Just a kind of primal struggle of nature itself.

I was fascinated, really so, by the art that I could see. As she neared the end of her life there was one tryptich like one of McCahon's but it was quite different. In her own way she went beyond McCahon. Her turning back to her memories of the land she had seen, and by painting from memory, she avoided any trite realism. Some of those works I think are among the greatest of their kind. She has been neglected.

At least this might help to restore her value. It is true in general that stylistically she was possibly "behind the times" but she was aware of art around her (although I don't think she was interested in theory, she theorises or talks acutely about various artists though, including Frances Hodgkins, McCahon and Woolasten, but she also mentions Hoffman the abstract artist, Golpas, and the young (then) John Reynolds. She read interesting books and her son was the poet Michael Jackson whose work I don't know but I see he has a repuation in anthropology as well as having written stories, poems, novels. all her children have done well. I met one of her daughters, Juliet Batten who is an author and artist.

In here art she took an old form but fiercely concentrated on it to create very intense works. For her, almost as for say Turner or Van Gogh, she felt that the land, "reality", was alive: the book has good plates but using a magnifying glass I moved in close and noticed that this greatly enhanced the works. The land and the landscape seem to move and even whirl with energy. There are no signs of the human, these are more than landscapes: they are the mind, the created reality. Some of them are almost Fauvist, expressionist rather than impressionist. Some seem like (in my imagination) the starkness and strange beauty of Patrick White's Australia (she read him inter alia). She was certainly a great painter in this mode.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.