Peter Ireland – 5 September, 2016

There is no way the photographer as a human being could disengage from this patient recording. Yet Veling’s apparent detachment makes the story all the more affecting. While his personal discipline is evident here, some of the credit must go to his thorough comprehension of what the documentary tradition entails in terms of practice. The art photography mode encourages the romantic notion of “self-expression” - which is why it's so digestable for the art crowd: something they recognise.

Tim J Veling,

D,P,O.

Christchurch, 2015.

(A sequence from this forms part of the group show Contemporary Christchurch at CoCA,

20 August - 6 November 2016.)

Old soldiers almost never talked about their war experiences. In the rare instances of them doing so, the last topic discussed was the killing of their young mates and comrades. It’s unstated but generally agreed: people avoid talking about death. Sex is meant to be the last Great Taboo, but it’s the Grim Reaper who’s really the proverbial “elephant in the room”. The joke goes that in life the only certainties are death and taxes, but all joking aside, most of us would rather contact the IRD than seek out a funeral director. The IRD deals in financial years, but the funeral business is all on the never never. Woody Allen pretty much summed it up with his quip “I’m not afraid of dying - I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

Death has been, perhaps, the most nagging concern of the human species, even if expressed in massive denial. Some of the most lasting monuments of civilisations have been structures dealing with the ghostly phenomenon of death: from Egyptian pyramids to our relatively modest cemeteries, their materiality is destined to last - stone, marble, concrete - even if the subjects of the objects have already gone.

Medical advances over the past two centuries have distanced us from death: people generally live much longer and the mortality rate for children has fallen dramatically. Death has also been medicalised: more people die in hospitals, hospices and in care facilities - and industrialised, with funeral homes taking care of the dead almost from the moment of the last breath to those final moments at a cemetery or crematorium (1). The intimate, hands-on family experience of just four to five generations ago is no more.

Museum files are replete with many instances of 19th century photographic images of the deceased, particularly dead children, laid out as if just asleep. It’s as if bereaved parents needed to substitute the living with such images, thus confirming photography’s intimate and long-standing relationship with memory and consolation. The birth of photography made this commemoration possible - a tradition barely outliving the century of the medium’s invention - a remembrance now tending to make us uneasy, our having in the meantime separated ourselves further from the facts of death - even sorrow is sublimated by calls for celebration, denial now having a “positive” spin.

Photography has seldom shied away from death as a subject (2). One of the medium’s first self-portraits, in 1840, features the photographer as a drowned man. Hippolyte Bayard’s rather melodramatic metaphor was his protest at being denied recognition as one of the inventors of the process known as the daguerreotype, his frustration registering in this compelling image of suicide. As the ultimate triumph of realism, photography depicted ravenously all aspects of daily life, including the termination of it, not because the photographers were voyeuristic sociopaths but because death was there, up close and personal.

Light years away from the inoculating idealisms of art photography, the documentary tradition has always remained committed to the gritty particulars of realism (3), the whole span of life from birth to death (4). Its crusading wing of social documentary sometimes took physical death as its subject, but more often kinds of social death as the result of poverty, injustice and inequality. W Eugene Smith’s famous essay Spanish Village published in Life magazine on 9th April 1951 is a memorable case in point. It depicted the still medieval conditions prevailing in a small town at the time of Franco’s dictatorship, and included images of a family dealing with the death of an elderly man.

Richard Avedon’s seminal book Portraits book of 1976 was distinguished by its merciless take on the rich and the famous. The flattery usually implicit in formal portraiture was here discarded for a “warts, wrinkles and all” depiction of personalities, the photographer’s fame leading his subjects willingly to the slaughter-house of his pitiless lens. Especially notable, however was the series of portraits of his aged father, tracking the relentless passage of his terminal disease - a tribute both to the faith of his father in his son’s project and the younger Avedon’s own fearless tenacity.

This description fits exactly Tim J Veling’s own project, embarked upon at the diagnosis of his father Pete’s incurable cancer on 30 October 2014 and concluding on the day of his death, 24 March 2015. The book contains 104 images in colour selected from the larger body of work, and sequenced chronologically. Three pages of text witten by the photographer precede the images and a third of a page follows them. Their spare and moving honesty matches the images exactly.

The book’s title - D, P,O. - is “how he [Pete] always signed off; shorthand for Dad, Pete, Opa” and gives an early clue to the book’s intimacy - one that is never mawkish, or burdened with all the idealistic assumptions and expectations the notion of “family” can drag in its wake. In passing, Tim Veling, an only child, documents plainly and without judgement his family’s particular dysfunctions: his parents’ divorce when he was in his early teenage years and his father’s later “drinking problem”. As he’d opted to live with Pete, it became his problem too.

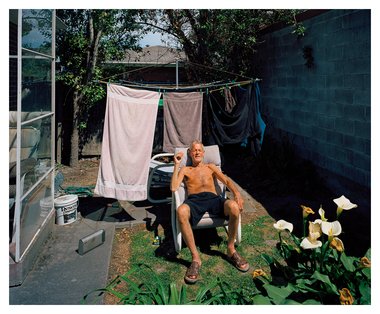

The resolution of this dilemma is a central part of the photographer’s story. Pete was a smoker as well, and continued to enjoy this relaxing and reflective pleasure even after the diagnosis of his lung cancer, a fact clearly evident in many of the photographs.

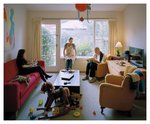

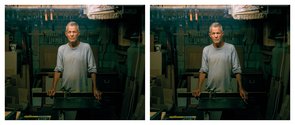

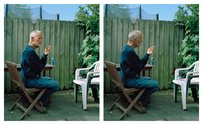

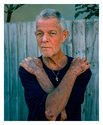

This back-story is merely a frame for the images which in their undramatic but relentless sequencing constitute a front-story that never shies away from the big story, but remains shy of any sentimental melodrama. Even though a lot is happening not much happens in the actual photographs: Pete has a smoke, has a snooze in the sun, surveys the industrial tidiness of his workshop, visits his son, takes company with his former partner, his brother, his mates, stands in the garden holding his only grand-daughter, looks fearlessly into the camera, a gaze without pity.

There is no way the photographer as a human being could disengage from this patient recording. Yet Veling’s apparent detachment makes the story all the more affecting. While his personal discipline is evident here, some of the credit must go to his thorough comprehension of what the documentary tradition entails in terms of practice. The art photography mode encourages the romantic notion of “self-expression” - which is why it’s so digestable for the art crowd: something they recognise. The documentary mode doesn’t involve any suppression of the heart, though (5), but it does require a much cooler head. Additionally, the art tradition has assumed the supremacy of single images, where any series as such - say, Monet’s haystacks, McCahon’s noughts and crosses, or Fiona Pardington’s glass unicorns - is viewed only secondarily for comparative purposes. But the serial approach is at the heart of documentary, and single images there function much like the words in a sentence. In the photographic documentary tradition whakapapa is created by the artist: in the art tradition it’s imposed by art historians.

There’s a kind of disservice to the project as a whole to single out any discrete images - just as isolating words from their sentence pretty much strangles the meaning. But the principle of merism may pertain, whereby the whole can be suggested by delineating some of its parts. Veling often pairs images virtually the same, but with slight variations that more than double the impact. D,P,O. is unpaginated, but each one, or pair, carries the date. A pairing dated 16-01-2015 depicts Pete sitting on the steps of his son’s suburban flat, cigarette in hand, eyeing the photographer. The pair differs in two subtle respects: firstly, the inclination of Pete’s head; secondly, the photographer’s daughter is seen through the window to the right. In the first image she’s smiling at her working father, in the second she’s looking skyward in a thoughtful way as if anticipating the future.

In an image dated 03-03-2015 - and titled Self portrait with dad - Pete is depicted in profile, resting in a deckchair in a small, fully-glassed porch, having another smoke and in reflective mode. Reflected in the glass as a dark shadow, the photographer’s head appears as an imprint on his father’s body as startling and disturbing as that of the miraculous sudarium, the veil of Veronica in the Passion of Christ. This complex re-imaging combines an historical forecasting of death with a process at the heart of photography in such a compelling way that recalls Serena Bentley’s canny description of the medium as “a complicated tension between fact and fiction.”

Two images dated 06-03-2015 feature two crosses in head-and-shoulder close-up portraits. Pete is wearing around his neck a small coptic ankh cross (6) and with his arms crossed over his chest, his hands grasping his shoulders. In the first image he’s looking away to the left, in the second directly at the camera. This simply composed and very direct latter image is an unforgettable portrait of an individual man, but it’s also a deeply affecting portrait of the unfathomable dovetailing of life and death. D,P,O. is a brave and beautiful book, human to the core. The art of photography.

Peter Ireland

(1) Bridgit Anderson’s photographic essay Caring for the Dead of 2005/06 is a telling example of this. It’s one of the projects covered in the Place in Time: the Christchurch Documentary Project; see their website.

(2) The very medium itself has been characterised as a form of death, particularly in the critical writing of the 1980s and ‘90s.

(3) That “ism” is crucial, indicating a style of depiction, not an automatic link to what’s called “reality”. A traditional Indian observation has realism as one of the fifty-seven varieties of decoration.

(4) Not always straightforwardly. The famous MoMA Family of Man exhibition in 1955 is a case in point. Ostensibly it did track the whole span of life between birth and death, but its main aim was one of reassurance - propaganda, if you like - that after the horrors of World War II there were still human values needing investment in. It was also a subtle advertisement that American values were the way of the future. That many of the images chosen were, emotionally, only one step north of Norman Rockwell’s nationalist pieties seems to have been neither here nor there.

(5) The documentary tradition has often been faulted with being too passionate and involved, particularly that central strain of it called “social documentary”, which is seldom less than crusading in one way or another.

(6) This is in the shape of a “T” with a small circle or, usually, oval surmounting it. Originally an ancient Egyptian symbol for life it was later co-opted by the Copts as one of their forms of the Christian cross.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.