Peter Ireland – 14 May, 2017

It doesn't seem to have been noted that, over those same years, single-medium group shows have become rarer than the kakapo, the disappearance accounted for by, firstly, a far wider range of art practice deserving exposure during that time and secondly, a theme-based approach within exhibition culture. Were a curator to mount a show of Sydney's work, what sort of theme might thread it together? Raking light? Abandoned railway stations? Dusk?

New Zealand Listener, Clare de Lore’s interview with Grahame Sydney, May 5-12, 2017, pp 26-31.

No memory of having starred

Atones for later disregard,

Or keeps the end from being hard.

Robert Frost (Provide, Provide)

Practising full-time artists encounter a few problems. They generally work alone, have an uncertain, irregular income, harbour doubts about their value and direction, fears about their status and credibility and, probably, nurse resentments towards curators and critics who fail to recognise their genius. These occupational hazards can stew away in studio solitude. There are neither raises nor performance reviews to steady the artists’ sailboat through life: only a prospect of the choppy seas of incipient paranoia.

Many artists seem to fraternise largely with other artists and art world operators - the superficial conviviality often masking an anxious but determined competitiveness with peers, and neediness with the curators, critics and dealers - these relationships likely to reinforce the tendency to paranoia rather than dispersing it to the four winds. The art world’s rife with gossip, rumour and the expression of singular opinions, such flotsam and jetsam delicious distractions from any reliable fathoming of a firmer seabed or predictions of looming reefs or beckoning shallows.

Given these conditions, the thing we call perspective is almost inevitably elusive. It’s unlikely any notion of “the artistic temperament” is going to include sound judgement - or even much in the way of self-reflection. In this scenario, introspection is less prevalent than self-projection.

Complicating these circumstances is the trajectory of the usual successful individual artist career. Beginning with showing promise at art school, the luckiest are picked up by a dealer the moment they pick up their degree. Inevitably a boost to self-confidence this launches forth the artist into the world - albeit the narrow and often mildly hysterical and self-referential arts’ sector where any regard for perspective is tantamount to letting the side down. What passes for success in this environment is the artist’s reward: exhibition and residency opportunities, sought after by collectors, written about glowingly by academics, collected by major institutions and included in equally major shows - perhaps even ending up at the Venice Biennale.

The English actor Beerbohm Tree (1852-1917) put the situation nicely: “The only person to have survived being lionised was Daniel.” After a decade or two of early success any artist faces the challenge of maintaining their profile and remaining relevant, never easy in the fast pace of change now and the thirst for novelty in the sector, to say nothing of a deep-seated social longing for the promise of youth - promise sometimes mistaken for simply looking good. In 1960 there were hardly any artists in New Zealand able to live by devotion to their art full-time. The following decade saw the multi-layered construction of a support network (dealer galleries, more professional public galleries, the Arts Council, private collectors etc) which set artists born soon after WWII - including Grahame Sydney - on the road to professional practice. By the 1980s there were dozens of artists living by their work. That generation is now becoming elderly, and as such is the first to have had observable, sustained life-time careers. Most of them, probably, would now read Robert Frost’s words above with grim recognition.

It’s given to few artists to continue an exponential development of their work through to the end of their lives: in the Western tradition Titian, Rembrandt, Goya, Monet and Cezanne spring to mind. Here there are not many more than Walters, McCahon and Woollaston - artists of a generation without the pressures of profile maintenance and commercial culture, but whose late work transcended the boundaries of what they came to be known for. In retrospect, the work of most artists vaunted in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s seems subject to New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl’s withering judgement of “period décor”.

On the face of it, Sydney has had an exceptionally successful career in terms of selling and profile, circumstances that might be the envy of perhaps up to 80% of full-time artists. From his being picked up by Peter Webb in 1974 and selling solidly ever since to eager and often wealthy private collectors, through his many very popular survey shows at the public galleries (1) and many impressive books going through numerous re-printings and gaining awards, to many interviews and profiles in a wide range of magazines throughout his creative life, Sydney might be expected to view his experience with pride and satisfaction (2).

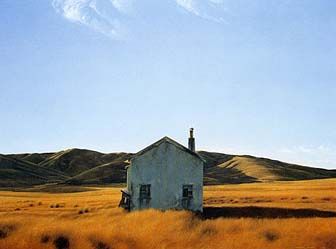

But no. Over the past couple of decades his interviews and other statements have revealed a growing impatience with mere commercial success and a gnawing need for a critical success the mandarins of the art world seem determined to deny him. This Listener interview is the latest and perhaps the most explicit of these. After de Lore lists his recent exclusions she asks him “What’s the issue, in your view?” He replies: “I have a suspicion it’s a combination of being a realist, a regionalist, and not needing a dealer. The art world is a relatively closed operation, where they look after each other within the trade, and the fact that I operate outside that boundary is not advantageous to me in that respect. You would be a fool to think everyone loves what you do, but I feel disappointed that even someone who dislikes what I have done, and continue to do, can’t be sufficiently objective to see it has a place in New Zealand art.” Earlier on in the interview de Lore asks the artist “Who’s buying?” and he replies: “Most of the big canvases go overseas, to expatriates. I think it is to do with their nostalgia for New Zealand. They are often people who are well established, doing well and longing for home in some corner of their emotional heart. The paintings I do seem to strike those chords for them.”

The remote Cambrian Valley in Central Otago - where the artist lives - is probably among places on the planet least conducive to maintaining an overview of what’s happening in the art world and why it’s happening. The horizon may be filled with paintable mountains but perspective might well be blocked by them. There are five pertinent remarks in the above quotations calling out for examination: the notion of a realist artist, the nature of historical regionalism, the emotion of nostalgia, the seemingly closed operations of the art world, and Sydney’s wish for some “sufficient objectivity” in curators and critics.

Sydney gives the impression that an artist’s style is akin to supermarket shopping: something picked off a shelf as an act of choice among many. If not realism why not late Mannerism, or even Byzantine iconography? Artists’ styles tend almost universally to be a response to the social/historical conditions of the time. It’s no accident that the style called realism - and a style is all it is, not some privileged insight into “the real world” (3) - arose in France in the mid 19th century at the same time as the invention of photography, and for similar reasons. And it’s no coincidence either that an American response in the later 1960s to Pop Art was a short-lived but highly visible movement called Photo-Realism (4) which tended to settle on and rejoice in urban subjects. Neither is it a coincidence that this movement reached its zenith at the very moment when many of Sydney’s generation were susceptible to the contemporary attractions of current styles. The difference with Sydney’s subject matter is his eschewing urban subjects for rural ones, albeit elevated into the sublimely empty - but classically full - magnificence of the New Zealand landscape. Where the rest of the world regarded Photo-Realism as an interesting art historical moment, somewhere in a remote valley in Otago its spirit lives on, almost as mythically as the last moa confined to an even remoter valley in deepest but nearby Fiordland.

The development of what came to be called regionalism was a longer historical phenomenon but with similar roots in time and place. It suited Modernism’s agenda to dismiss it as a merely reactive (5) to its grand vision (6), but over the past few decades the movement has been assessed somewhat more soberly by art historians - perhaps as assiduously as contemporary artists show little interest in it. There is no denying that fashion plays a part in any art practice: wanting to belong is a deep social instinct (the mirror image of being a beleaguered individual is its pathology), but epithetically it’s usually a defensive accusation. Modernism was born out of and flourished within an urban European context: Des Moines, Johnsonville and Geraldine were more than just geographically distant from this and the native artists naturally gravitated to regionalism as their form of expression, the work of the much-admired Rita Angus providing the quod erat demonstrandum. That was then: this is now. Like it or not, globalisation’s a fact of life, and in such an environment the notion of regionalism finds itself totally without oxygen - even in the cleaner air of Central Otago.

Whatever nostalgia may have been an element in historical regionalism was probably largely a Modernist invention, another arrow in its quiver of dismissal. With a later, regionalist-inspired artist such as Norman Rockwell it’s too easy to mock the backward-looking values the covers of the Saturday Evening Post promoted and use his work to smear the whole movement (7). Historical realism was, if anything, a commitment to facing up to the facts of ordinary contemporary life - marking a turning away from the requirements of the church, the rich and the powerful - and artists from Courbet to Simon Denny have resolutely followed this agenda, in which there is no room at all for the looking back nostalgia implies.

“Pure” landscape painting devoid of staffage was a child of the Romantic movement, and a vehicle for the Sublime where the forces of Nature were depicted as a more credible option to divine diktats in terms of explaining the world’s workings but still demanding a similar sense of awe. In England, the sturm and drang of artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and de Loutherbourg got watered down (8) into the polite, more topographical approach of landscape watercolourists such as John Sell Cotman, Thomas Girtin, John Crome, David Cox and Peter de Wint (9), a tradition taking root in New Zealand in the latter half of the 19th century, capitalising on a scenery that’s become enmeshed in notions of “national identity”. Landscape painting dominated local art for the following century, and now continues - in a pretty exhausted state - by those art societies still existing. Sydney’s photo-realist style has always sat at a slight right-angle to this history, at once acknowledging it as a source, but updating it - with more than a nod to photographic formalism - in the way that Victorian houses were modernised in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Recently the artist has “come out” as a photographer, but his work, from its beginnings, has suggested he always was. Though, as perhaps with Eric Lee-Johnson, this was kept under wraps lest it injure his painterly reputation in an art world then less accommodating of the “new” medium. Unfortunately this delay has meant his photographs are stylistically indistinguishable from his paintings, which was never the case with Lee-Johnson (10). The Listener interview (click here) is illustrated by five works, four of them completed in the last five years. One, Nevis Prayer of 2012 (p.31), depicts a marble, cross-shaped cemetery headstone set against a lowering sky, an image owing an obvious but rather candified debt to Laurence Aberhart’s work of the 1980s, as does the accompanying Waipiata Angel of 2013 (p.30). Is this appropriation somehow legitimised by the still-extant notion that a painting automatically has more weight than a photograph? Curators and critics may be the villains of the piece, but at least most of them have crossed that particular Rubicon.

As to the art world being a closed system, that has been the case in the West since at least the 15th century and no amount of agonising and complaint by artists is going to make much difference anytime soon. If there’s any connection between “realist” and “realism” this is where it needs to kick in. Curators are as much invested careerists as artists are, keeping a weather-eye on chances for promotion. In the small, tightly-connected art world of New Zealand no aspiring curator is going to risk advancement by opining that, say, McCahon’s bunkum and Sydney’s the best thing since Michelangelo, even if it were true. Sydney’s desire for some “sufficient objectivity” in this sector is simply wishful thinking.

The system is one thing - easy and perhaps foolish for any artist to attach a paranoia to it with all the fixture of a limpet to a rock - but, call them objective or not, there may well be a number of credible reasons why this particular artist, to paraphrase the interview’s rather melodramatic title, hasn’t “been included in shows of contemporary NZ painters for years.”

It doesn’t seem to have been noted that, over those same years, single-medium group shows have become rarer than the kakapo, the disappearance accounted for by, firstly, a far wider range of art practice deserving exposure during that time and secondly, a theme-based approach within exhibition culture. A pertinent example being the current McCahon show at Wellington’s City Gallery, which examines the artist’s sometimes bumbling attempts to acknowledge Maoritanga. Were a curator to mount a show of Sydney’s work, what sort of theme might thread it together? Raking light? Abandoned railway stations? Dusk?

Again, increasingly, artists are not only plumbing the parameters of contemporary life, the work of many of the younger of them focuses on social issues such as inequality and surveillance, and environmental challenges such as climate change. It’s not the 1970s anymore - it’s the 21st century.

At a time when just about every week brings another report of the dire condition of the country’s rivers, the environment generally, as well as the social impacts of high levels of immigration - putting paid to the myth of 100% Pure - Sydney continues to retail a style of painting promoting unspoilt and unpeopled landscapes. Just where does a confessing realist connect with escapism? In 18th century England, the new industrial magnates started collecting art, their favourite artist being the undoubtedly great painter Claude Lorrain. His classical vision of a golden Arcadian past provided a kind of balm for the very people responsible for laying down the first plank in the severe environmental crisis we, our children and grandchildren now have no choice but to face.

The first question of the Listener interview is this: “Is it Central Otago or nowhere, as far as you’re concerned?” The artist replies: “I couldn’t possibly live elsewhere. Today is grey - a dull day - but normally it is beautiful. We live with the Hawkduns on one horizon - that’s the signature range for me - and I built here so I could see them every day. Mt St Bathans is to the north, with its head in the clouds at the moment. It is like living in a theatre.” Head in the clouds? Living in a theatre? What more can be said?

Peter Ireland

(1) Christchurch 1976/77, Dunedin 1981 and again 1999, between 1999 and 2002 the Hocken Library toured nationally 35 of his paintings, and in 2001 the Auckland Art Gallery hosted a show that over its 3-month run attracted 34,346 visitors. Other NZ artists have accrued greater attendances, but Sydney retains the record for a show there with an entry fee.

(2) In 2003 he was made an Officer of the NZ Order of Merit for services to art.

(3) There’s an Indian saying that realism is one of fifty-seven varieties of decoration.

(4) Major exponents being Robert Bechtle, Robert Cottingham, Richard Estes and Ralph Goings.

(5) It sometimes was; the case of Thomas Hart Benton being perhaps the most extreme, and often quoted as if individual extremity were equivalent to a widespread phenomenon. As usual, it was just guys aping what their mates were doing: in New York it was abstraction, in Iowa it was “regionalism”. The only real difference was that New York held the high moral ground.

(6) The painter Rob Taylor was very good at this when art critic for Wellington’s Dominion newspaper in the 1980s.

(7) As Blake Gopnik observed of Rockwell: “If the experts haven’t found new reasons to like him, they’ve found new ways to look at his achievement”, in “Telling Stories” a review of a Rockwell show at the Smithsonian, Guardian Weekly, 16 July 2010.

(8) Turner was the great exception, but his landscapes gradually exchanged any realism for abstract sworls of pure paint.

(9) In Emma, Jane Austen summed this up: “It was a sweet view - sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a bright sun, without being oppressive.”

(10) It’s this writer’s hunch that Lee-Johnson was a major photographer, and in time his work in this medium will be valued far above his painting. See my review of John B Turner’s Eric Lee-Johnson: artist with a camera, in Landfall 198, Spring 1999, pp 296-298.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.