John Hurrell – 11 August, 2017

Embracing popular tunes, primal therapy, silent aural voids (in theory anyway), recorded documentation, Hollywood soundtracks, collaborative whispered texts and interpretable sonic transcriptions, 'Shout Whisper Wail' extends over a wide spectrum of listening sensation and functionality; a range of avant-gardisms.

Auckland

The 2017 Chartwell Show: Juliet Carpenter, Julian Dashper, et al., Alicia Frankovitch, Jacqueline Fraser, Marco Fusinato, Samuel Holloway, Janet Lilo, Biljana Popovic, Stuart Ringholt, Luke Willis Thompson

Shout Whisper Wail

Curated by Natasha Conland

20 May - 15 October 2017

Ten mini exhibitions from various artists represented in the Chartwell Collection are presented here in an exhibition that is smaller in floor meterage than earlier Chartwell shows, but nevertheless tightly compact. While it looks cohesive, the disadvantage is that the thematic content revolves around sound, as you can tell from the title, and in this area it is poorly designed. The works need to be spread apart.

Consequently over the school holiday period particularly, the show dissolves into aural chaos: feral children banging on et al and Holloway’s piano; jumping up on to Ringholt’s ute tray and shrieking. To grasp the point of a subtle artist like Juliet Carpenter (who is terrific with directing and writing quietly articulated, spoken text) is impossible. You have to wait till the brats have returned to school—and make sure you avoid weekends.

Embracing popular tunes, primal therapy, silent aural voids (in theory anyway), recorded documentation, Hollywood soundtracks, collaborative whispered texts and interpretable sonic transcriptions, Shout Whisper Wail extends over a wide spectrum of listening sensation and functionality; a range of avant-gardisms.

et al. and Sam Holloway set the scene with their installation of drawn on, staved manuscripts, easels with sampling headphones, freestanding speakers, and upright piano for performances. Like the confrontational aural installations Merylyn Tweedie and L. Budd made in the late eighties and mid-nineties, the sonically collaged, computer treated texts (eg. See this fist. This is my moral authority) are disturbing, but unexpectedly the music with Holloway has an unforeseen sweetness that encourages their audiences to linger.

The veneer-covered floor, steps and ornate shelter with colonnade—constructed by Biljiana Popovic as a tiered barrier to stand on in front of Juliet Carpenter’s collaborative video with Gregory Kan (text) and Sorawit Songsataya (animation)—presents in silhouette just under its ceiling the social identity term ‘intersectionality’. One assumes this is in response to Carpenter’s use of the skywritten phrases ‘cast out of heaven’ and ‘high water or hell’, and possibly too—visually—the also silhouetted ‘welcoming’ words of the infamous wrought-iron entrance to Auschwitz: Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Sets You Free).

Popovic’s spectacular installation provides an effective physical barrier to the sound system of Carpenter’s project; we can’t get close to it, so Carpenter can carefully control the audibility of her and Kan’s unusual text, written to be whispered or spoken by Songsataya’s heads. The four audio versions (with different volumes of female voices) say enigmatically:

It has been 5 or 10 years with nothing. That’s enough for me. Your voice sounds like your name should be ‘Caroline.’ If one of us doesn’t get a minor cancer then we haven’t worked hard enough.

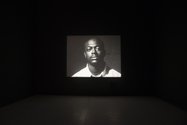

In the bay next door is a silent projection of two Luke Willis Thompson videos, moving (but almost still) images of two young black men whose mother or grandmother were murdered as a consequence of police brutality and racist aggression in London. The work’s title (Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries) is a clever manipulation of Duchamp’s ‘malic moulds’ from his Large Glass, implying that hatred or desire for revenge is fluid thing, poured from one generation into another into (masculine) moulds that set up retaliatory violence.

Marco Fusinato’s contribution to the show is a massive screened photograph of one lone rioter brandishing a rock at a long line of advancing police. The horizontal grey image is chilling with its tension, as you mentally envisage the mayhem about to be unleashed a few seconds after this photo. The scale of the work implies that the gallery visitor is also a rioter caught up in the drama.

Nervous gallery visitors are also—in another part of the gallery—invited by Stuart Ringholt to release other hidden (but personally accumulated) tensions vocally from the spotlight deck of a shiny white ute tray. These primal screams are in private (the space is roped off) but meant to be very audible. Psychotherapy as art. Finding visitors who are not frivolous exhibitionists doing it for a giggle, but who take the opportunity for mental/bodily stress-release seriously, is the challenge. A very rare breed in Auckland.

Next to the Fusinato, Alicia Frankovich presents a video of a filmed outdoor performance that is choreographed like a dance. Light and fast moving it is based on the famous comical boxing match, using a ref and two boxers, in Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931). It is more about feinting and horizontal spiral manoeuvring, with nimble and delicate footwork, than pretended punching.

Another Frankovich work is a kinetic sculpture of a suspended flat disk, bobbing like a yoyo to emulate a dribbled, bouncing basketball. Conceptually connected on the other side of the room, on the far wall, near two red gymnasium climbing ladders and a neon quotation (possibly about marginalisation) from the film Dirty Dancing, is a neon basketball hoop from Janet Lilo, a symbol perhaps for economic prosperity and desirable social status. Lying dumped on the floor, the same goal has also fallen in a three-channelled video of a dilapidated gymnasium. Here in this desolate and ravaged space, camels exercise on treadmills, and smoke-belching underground dragons appear.

The last section of Lilo’s video changes in mood. It features recorded popular music and multi-levelled song lyrics set out with elegantly imaginative fonts, much as she did earlier in her Te Uru survey with a work that used DJ Snake’s Middle that featured the British singer Bipolar Sunshine. For Shout Whisper Wail however Lilo uses St Pablo, a Kanye West song that features uplifting hooks and verses written by another British singer, Sampha that she concentrates on:

You’ve been treating me like I’m invisible / Now I’m visible to you…I’m wishing that you saw my scars man / I’m wishing that you came down here and stood by me…Yeah you’re looking at the Church in the night sky / Wondering whether God is gonna say ‘hi’…And you wonder where is God in your nightlife.

Julian Dashper’s contribution to this show is a vitrine of various vinyl discs and their covers that he released as part of his art practice, plus about twenty digital recordings (of their content) that you can listen to on headphones. It is not so much music that is on these as the aural documentation of events, and even that is not as particularly important as the process or gesture of placing these artworld sounds on discs: packageable labelled (sonically-embedded) circles that can be hung on a wall if wished—as a sort of CV.

The installation by Jacqueline Fraser is a shiny alleyway that leads to an enterable square space lined with glittering golden tinsel streamers, and a suspended smaller square (of red streamers) in its centre, onto which is projected the film Mississippi Grind. This movie, about two friends who are working gamblers, is heard more than seen—the image disappears—its spoken sound mingling with a separate musical soundtrack coming from high in the ceiling.

Fraser’s large, framed, glassed-over collages, positioned on three of the ‘flax-lined’ walls, present overlapping images fastidiously torn from the pages of fashion and décor magazines. Beautiful male and female models in skimpy costumes, looking bored or wearing masks—or historic images of celebrity friends chatting at parties—are juxtaposed with decorative curtain patterns in matte and glossy sequins and inverted images of ‘eye’ sculptures on marble floors. With the ornamental wall motifs the collages look architectural, part of their ‘outside’ being internalised, but incorporating collaged images of institutional gallery spaces too. Conspicuous are works by Andy Warhol and ‘mutated’ art historic effergies by Glenn Brown.

Conland’s show is not the sprawling project of past Chartwell exhibitions which sometimes had an inviting unruly chaos (eg the Daniel Malone installation), but the aural theme here is coherent and easy to grasp, even though other salient threads—like multiplicity of selves, political urgency, creative spontaneity, psychic release and the wish for audience interaction—when it comes to practicalities around installational detail, inevitably undermine.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.