John Hurrell – 15 October, 2017

If you look at the line up of artists who had the Fellowship from 1966-2015, the diversity (and range of quality) at first glance is staggering. It is surprisingly a motley and incongruous bunch. Why some of these recipients were so lucky is baffling, although obviously it is always hard grasping historic context (and social politics) in hindsight. However, about 75 % provide ‘the good oil.’ That is a healthily high success rate.

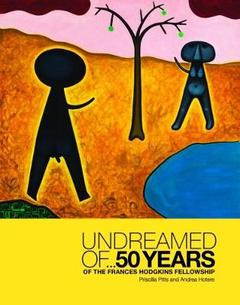

Priscilla Pitts & Andrea Hotere

Undreamed of…50 years of the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship

Essays, multiple biographies and foreword by Priscilla Pitts, Andrea Hotere, Joanne Campbell, Sharon Dell

Designer: Karina McLeod

Hardcover, full colour illustrations, 224 pp

RRP $59.99

Otago University Press, September 2017

This extremely informative, generously illustrated, hardcover book looks closely at a Dunedin-based institution that has nationally and annually propelled the visual arts astonishingly for over fifty years now-a wonderfully generous award where a university lecturer’s salary allows an artist to work in a provided studio free from financial anxiety-in a city where, when Otago University’s fellowship was originally initiated, there was not even an art school.

Most of the recipients have been painters and sculptors, with the occasional printmaker, photographer, installation, performance or video artist. Bearing this last point in mind—and considering profile, financial reward or prestige—it might be argued that the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship has now historically been superseded by the Walters Prize, the Wallace Trust Awards and perhaps the Creative New Zealand selections for the Venice Biennale (especially where those more international accolades overtly embrace other allegedly more ‘contemporary’ or ‘conceptual’ artistic disciplines like video, film, photography, new media, performance and installation) and so can overall be considered an espousal of comparatively conservative and orthodox art practices.

If you look at the line up (click here) of artists who had the Fellowship from 1966-2015, the diversity (and range of quality) at first glance is staggering. It is surprisingly a motley and incongruous bunch. Why some of these recipients were so lucky is baffling, although obviously it is always hard grasping historic context (and social politics) in hindsight. However, about 75 % provide ‘the good oil.’ That is a healthily high success rate.

Possibly the most absorbing sections of this book (as prolonged intensive reads) are the essays about the influence of the Fellowship and the nature of its benefits for the artists (Priscilla Pitts), and the processes of its setting up and maintenance mixed with looking at various supportive relationships within Otago University (Joanne Campbell). Campbell is particularly interesting, as she is very good at ferreting out pertinent information—where the original legal documents are lost or confidential—by talking to Fellows who had inside connections. She discusses the various financial crises that threatened the Fellowship and how certain generous benefactors at different times came to the rescue to keep it going, and Charles Brasch is her main point of focus.

Brasch (1909-1973), the founding editor of Landfall, New Zealand’s first substantial literary journal (est.1947), was a true visionary, a poet, and essayist greatly preoccupied with the historical transformations of this country’s (British based) culture and the influences it absorbed. A man of independent means who was a sensitive and articulate observer, Brasch was exasperated by the dull philistinism of New Zealand culture, and loathed the conventional thinking of landscape painting projects like the Kelliher Art Prize. A passionate supporter of a wide range of disciplines, his charm, energy and enthusiasm attracted other creative intellectuals who also loved modernist experimentation. The fascinating collection of New Zealand modernist paintings that he acquired from his artist friends—along with many of his books and personal papers—is now housed in the Hocken Library.

In contemporary times, when councils running municipal institutions often casually cut funding for visual arts acquisitions with the excuse that private patronage will support it, Brasch’s secret initiating—with the help of other likeminded philanthropists like his London-based cousins Esmond, Mary and Dora de Beer—of the Robert Burns Fellowship (est. 1958), the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship (est. 1962), and then the Mozart Fellowship (est. 1969) within Otago University, was sensationally radical. Such foresight is rare now; imagine how rare it was in the late 1950s.

Following Campbell’s contribution in the publication are much shorter (but multiple) sections by Pitts (each artist’s Hodgkins year) and Andrea Hotere (their life/career trajectory with interview), discussing almost 50 very diverse individuals. These are also packed with informative detail, and though condensed are highly readable.

This is a great book for opening at random, dipping in and seeing what you can find, and discovering the existence of talent or works you may not have heard of. There is such a wide range of work style, method, subject matter and visual aesthetic that the inquisitive reader is bound to discover sections of intense interest comparatively quickly. And while I find myself blushing because it is so corny to say: a terrific Christmas gift.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.