John Hurrell – 14 September, 2018

As exemplified by the exhibition title for this international show of ten artists, “standing” means in the southern hemisphere. It is a pointed way of making the old ‘margins' the new ‘centre', flipping things over so Eurocentric values no longer dominate. This ethos is articulated in the pile of help-yourself textual posters by Swedish/Brazilian contributor Runo Lagomarsino: 'If you don't know what the South is, it is simply because you are from the North.'

Pakuranga

John Akomfrah, Fernando Arias, Regina José Galindo, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Runo Lagomarsino, Sarah Munro, Otobong Nkanga, Siliga David Setoga, Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Jian Jun Xi

From Where I Stand, My Eye Will Send A Light To You In The North

Curated by Gabriela Salgado

12 August - 21 October 2018

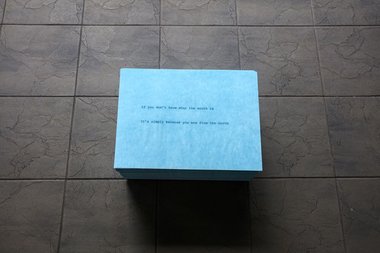

As exemplified by the above exhibition title for this international show of ten artists (taken from part of a 2015 London performance, Diaoptasia, by Nigerian Otobong Nkanga) “standing” means in the southern hemisphere. It is a pointed way of making the old ‘margins’ the new ‘centre’, flipping things over so Eurocentric values no longer dominate. This ethos is embraced by the Te Tuhi curator Gabriela Salgado and articulated in the pile of help-yourself textual posters by Swedish/Brazilian contributor Runo Lagomarsino: If you don’t know what the South is, it is simply because you are from the North.

Otobong Nkanga provides one of the key promotional images for this show and her three pale blue vitrines of enigmatic lithographic prints—symbolic diagrams that focus on the greedy exploitation of African mineral resources (amongst other themes)—are endlessly fascinating in their inventiveness. Each covered vitrine has three single pages, one double page and a quintuple page laid out on display. A superb colourist with precise tonal control, her abstracted unmodulated illustrations, with stringlike lines that link different components in a witty narrative, often feature clusters of disembodied arms with different tools attached. Casual blobs of abandoned ‘mixing palettes’ double as possible maps.

Regina José Galindo is a Guatemalan artist known for her uncompromising, very visceral performances that usually are about women’s or indigenous people’s rights. Her thirty-three minute film shows her standing naked and vulnerable in an open field while a huge digger with an unseen driver gradually removes all the soil around her, so she is left standing on a little grassy plateau in the middle of a giant chasm. The metal claw extracting the earth seems huge—and she is tiny. Beautifully filmed so that the contrasts gradually become evident, the driver of the machine controls the extracting claw with surprising delicacy, casually brushing fallen clods of topsoil sideways into the hole with exacting finesse. The poetic/political point is obvious: the insidious destruction of the traditional habitat of many Latin American indigenous peoples. More specifically it is a response to the attempted extermination of Guatemalan Indians in the early eighties by President Efraín Ríos Montt.

Aucklander Sarah Munro is mostly known for her elegant minimalist sculptures so the historical (and symbolic) narratives she presents in this show is a surprise. Referencing the famous bartering image by Tupaia-of Māori and English (in this case, Joseph Banks) doing a swap in 1786—Munro does eight versions, all embroidered on canvas, and framed. As a conceptual template there is not much subtlety: Māori offering food, fabric or specimen supplies that are indigenous in origin, English presenting in return noxious pests that will destroy them. It is didactic and pedagogical; but fun for children to identify the various creatures, plants and products being proffered-all rendered in thread.

Colombian Fernando Arias last had work in Auckland as part of the Space to Dream show. His film here looks at the wasteful consequences of prawn harvesting done off the Colombian coast by multinational companies, and the damaging effects the trawlers have on the small scale fishing done from canoes by local people who live in the rain forest. We see the labour intensive building of a canoe, and the discarding of small fish from the trawlers, sorted from the lucrative pawns and killed by being raked up and netted.

British/Ghanaian filmmaker John Akomfrah won a lot of admirers when his spectacular multi-screened installation Vertigo Sea was presented in CoCA in Christchurch two years ago. At Te Tuhi, his current—typically ambiguously poetic—work, single-channelled Tropikos, looks at English colonialism by having actors play the roles of Drake, Elizabeth 1 and two unnamed slaves as the boat moves up through Plymouth Sound and the River Tamar, laden with plunder from Sierra Leone and Guinea and stopping at forts. Shots of vegetation from those West African countries are incorporated, as are recited texts from Shakespeare, Milton, and Calderón de la Barca, plus imaginative fantasies where historic roles are reversed. Akomfrah loves the elemental, using it with evocative images to mesmerise you and nudge your mind into other things. In an earlier Nine Muses it was snow and blizzards; in Tropikos it is lapping water.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby looks at ‘blackbirding’ and the slavery that sustained the sugar cane industry in Queensland plantations; the kidnapping of South Pacific peoples from places like Vanuatu. As a descendent of such victims she critiques the role of Christianity in nurturing passivity within the enforced labouring communities. Her installation, Sweet Jesus, with the letters of Christ’s ‘Christian’ name rendered in brown sugar and resin, sardonically snorts at religious escapism—a gesture of rage rather than sustained articulated argument. On the wall opposite the three dimensional sugary text are three historic photographs of Melanesians in Queensland, one in the plantation fields, and another at a Church meeting where there is a mass baptism in a river. Three generations of young women are superimposed over the images on the photographic plates, making the point that the past will not be forgotten.

Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda also looks at history, particularly monuments to imperialist heroes where the original Portuguese or Russian figures have been torn down during wars of independence. The plinths of such ‘decommissioned’ statues then become podiums for temporary monuments featuring everyday citizens like the artist and his friends. Pomposity is now deflated, and the status of ordinary achievement (such as being sufficiently agile to climb) elevated. Henda includes old images of the statues before they were destroyed, alongside images showing the more recent post-colonial changes.

Over the last few weeks the activities of the United States President in Washington have come under extraordinarily intense public scrutiny. Capitol Hill has become the object of much public ridicule, and Jian Jun Xi‘s version of a toppled dome reflects this—though his focus is on imperialism. The rotunda is presented on its side and could be mistaken for a stumpy horizontal condom. Made of steel rods and plastic woven for cheap carry-bags, the red, white and blue dome is a symbol for overthrown (white) phallocentric imperialism: hollow, lightweight, tatty and very wobbly.

The three plastic domed lightboxes of Siliga David Setoga enclose photographic images juxtaposed with high visibility yellow, a fluorescent lemon so ubiquitous as to be almost unseen. Captain Cook, Dame Whina Cooper of Māori land rights march fame, and Tuila’epa Sailele Malielegaoi, the Prime Minister of Samoa, are all immersed in it—three politically divergent personalities. Captain Cook’s visits began the colonising settlement process by the English, Dame Whina Cooper raised the efficacy of the hikoi as a political tool, and Prime Minister Tuila’epa is controversial because he founded the Human Rights Protection Party (the only party in Samoa) which changed the commercial status of Samoan land from communal to sellable by individuals—and available to foreigners.

Setoga’s title, This Land of Plenty, plays off against the three personalities with their opposing attitudes towards land ownership, mixed in with apprehensive messages via public signage: Cook a warning hi viz vest; Cooper a protective road sign; Malielegaoi another warning. The provocative caption cannot obliterate the distinctions, anymore than the eye-popping yellow can. It spotlights the issues and pulls away.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.